UK green package looks a little blue [LNG Condensed]

The UK is heavily dependent on natural gas both for power generation and home heating – some 80% of homes have gas boilers. However, earlier in the year, as part of the Spring Budget, the government announced that from 2025 new houses would be banned from installing gas boilers and would have to turn to alternatives. In its ten-point green package announced in November, the government set a target of deploying 600,000 heat pump installations a year by 2028.

Retrofitting ground source heat pumps is not an easy option and air source heat pumps also entail significant changes to the whole of a home heating system, so incentives are going to have to be substantial to make this a success.

The government will also develop a ‘hydrogen neighbourhood’, then a ‘hydrogen village’ and then a ‘hydrogen town’, building on existing pilot projects, by the end of the decade, in which all the town’s heating will supplied by hydrogen.

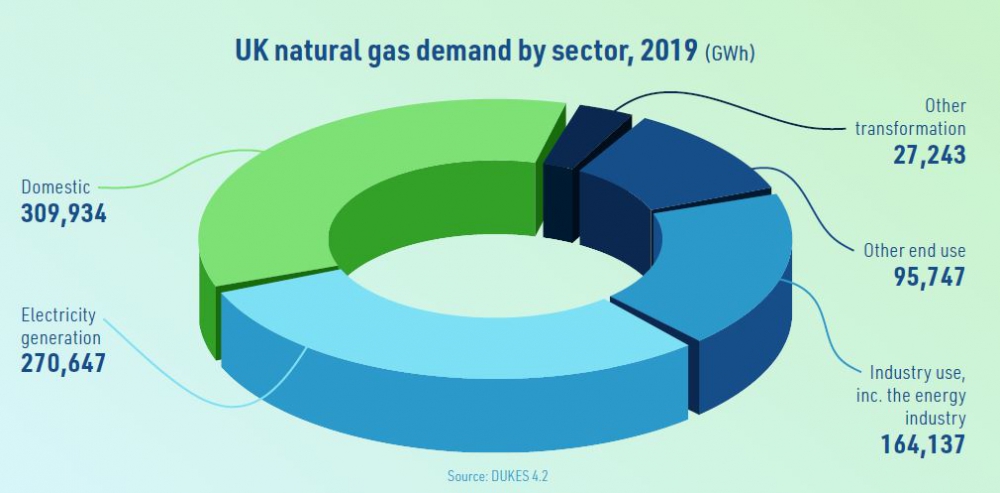

According to government statistics, total UK gas demand in 2019 amounted to 873,515 GWh, of which domestic use accounted for 310,000 GWh, or 35.5%, a slightly larger share than for power generation. If these policies are implemented, post-2025, there should be a long-term structural decline in UK gas demand for home heating.

Power generation

The power generation plans laid out in the green package focus on offshore wind and nuclear energy. For offshore wind, the government reiterated its existing target of 40 GW of capacity by 2030. This should roughly quadruple current output from the offshore wind sector which, in 2019, accounted for 9.9% of total electricity generation. This can only eat into gas’s share of the generation mix because coal-fired generation had already fallen to just 6.9 TWh last year. To put it another way, coal-to-gas switching in the UK is a spent force.

However, the other power generation element of the UK’s green package is far more speculative, resting on both existing nuclear technologies and new nuclear technologies, and the phrase ‘subject to value for money’ gets multiple outings.

The UK has just one nuclear plant under construction, which is well behind its original schedule. It is itself relatively new technology – a European Pressurised Reactor, being built by France’s EDF. It will the first new nuclear reactor built in the UK for 20 years.

The price of the electricity generated was agreed in 2016 via a non-competitive contract for difference (CfD) in which the strike price was set at £92.50/MWh in 2012 prices. The timeline for operation is the mid-2020s.

Hinkley Point C will have capacity of 3.2 GW, but by the time it comes on line half of the UK’s existing nuclear fleet of 9 GW will have started decommissioning, removing 4 GW of capacity.

Value for money?

The cost of onshore wind and solar photovoltaics are now well below the cost of any fossil fuel-fired technology. Combined-cycle gas turbines (CCGTs) are the cheapest fossil fuel source, according to investment bank Lazard’s October Levelised Cost of Electricity study.

Moreover, offshore wind power is likely to prove subsidy free from around 2025, according to a recent study led by Imperial College London, Offshore wind competitiveness in mature markets without subsidy. This concluded that the latest round of capacity allocations awarded last year could prove to be the first offshore wind farms to pay money back to the government under the CfD scheme.

The Lazard study put the range for onshore wind between $26-$54/MWh, CCGTs at $44-$73/MWh, while new nuclear came in at $129-$198/MWh, up 33% from 2009 in sharp contrast to onshore wind’s 70% drop and a 29% reduction in CCGT costs over the same time period.

As such, how likely is it that EDF’s second project on the books, Sizewell C, will pass the ‘subject to value for money’ hurdle? In addition, given the time it has taken to even start Hinkley Point C, it’s still uncertain completion, and the additional financial pressure it has placed on EDF, Sizewell C may not progress at all. If it does, it is unlikely to be completed until the rest of the UK’s existing nuclear fleet has closed down.

The second strand of the strategy is to put money into research and development for small modular reactors and advanced nuclear reactors. These remain developmental and, even if a viable commercial reactor can be made, the first of its kind will not be cheap. Any design will also have to go through lengthy regulatory and licensing procedures to ensure it is safe.

Despite the government’s apparent enthusiasm for nuclear power, its share of the UK’s current generation mix looks likely to be lower in 2030 than it is today. This, in turn, should keep the CCGTs spinning longer than might be expected.

It should also be noted that 40% of the UK’s renewable electricity generation in 2019 came from biomass. The Dutch government has decided to phase biomass out its generation mix altogether, while the UK government also looks likely to exclude new coal-to-biomass conversions from funding.

The reason is growing concern that biomass plants do not really deliver any greenhouse gas savings at all over the short to medium term. If policy around the fuel source tightens, this could leave a substantial hole in a number of European countries’ power sector decarbonisation plans.

Hydrogen strategies

In common with the EU, Germany, the Netherlands and France, the UK government has highlighted hydrogen as a promising fuel. The key difference in policy, with respect to Germany at least, apart from the interest in nuclear power, is a bigger commitment to carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS). While the UK was considering two CCUS clusters by 2030, these now have to be up and running by 2025, with a further two to be developed by 2030.

Moreover, the EU countries’ hydrogen strategies explicitly prioritise the production of ‘green’ hydrogen from low carbon power running electrolysers to split water molecules. They accept that some ‘blue’ hydrogen production may be necessary as a transitionary measure, but this requires CCUS. In Germany, the debate over CCUS is contentious and there is significant public opposition to the technology, owing to the risks of long-term storage.

The UK appears more relaxed because a legacy of its oil and gas production is a large number of potential storage sites offshore and far from populated areas.

The Dutch government, which is also supportive of CCUS, is also looking offshore and Anglo-Dutch CCUS projects are being developed which envisage carbon dioxide from continental Europe being shipped to offshore sites for storage in UK waters.

While the UK government’s green package sets a target of 5 GW of low carbon hydrogen production by 2030, on a par with the German strategy, the UK hydrogen plan, given its commitment to CCUS, looks more blue than green. A formal hydrogen strategy is expected from the UK government next year.

The CCUS clusters will attract up to £1bn in funding, which split between four does not look sufficient. However, the government intends to execute a process for CCUS deployment next year and decide on an appropriate business model in 2022. This is likely to be some form of public/private enterprise in which developers are sheltered from the long-term risks of storage.

Domestic gas production

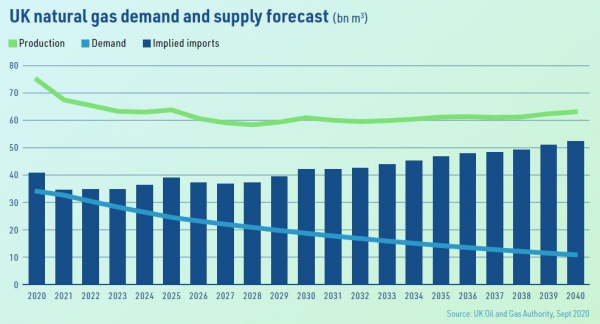

What does appear certain is the gaping hole in domestic European gas production is likely to get ever larger over the next ten years – faster, it would appear, than the decline in gas demand resulting from governments’ home heating and power generation plans.

The once giant Groningen gas field in the Netherlands is not coming back and production from the UK continental shelf is forecast by the UK Oil and Gas Authority to fall from 34.4bn m3 this year to just 10.7 bn m3 in 2040. Gas imports are projected to fall over the next few years, but get on an upward trajectory from 2024, rising to 52.4bn m3 by 2040.

Norwegian gas output is expected to remain stable until 2024 at just under 120bn m3, but to then slide downward to 90-92bn m3 post-2030, according to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate.

This implies rising imports of gas both for the UK and continental Europe even if domestic demand is curbed by environmental policies. In northern Europe, this effectively pits Russian pipeline gas against LNG, a battle which is likely to be fiercely competitive, and which should keep gas prices on a low price trajectory, a factor which generally supports demand, but not upstream investment.

Although it is not fashionable to say it, the most likely scenario with regard to Europe’s net zero by 2050 targets is partial success, with total decarbonisation more likely to be achieved in the 2050-2070 period. This is because the scaling up of green hydrogen production and establishing safe distribution and usage will take a huge effort.

As such, abated hydrogen production from natural gas could be the key a much higher level of success in 2050, making it more than simply a transitional option. The UK approach appears more open to this possibility and, while it is not a conclusion that will be welcomed by environmental organisations, it is possible that it proves more achievable in practice.