Two approaches to European wind [NGW Magazine]

The growing success of offshore wind in the UK could see gas demand forecasts pared back over coming years, as the latest low UK prices encourage calls for faster expansion. Onshore wind, however, especially in Germany is not faring so well, with rising prices, a failure to award capacity auctions and lengthier construction processes setting German plans back several years. This could leave room for gas to expand as nuclear and coal are wound down.

Gas remained the UK’s leading generation fuel in Q2 2019, with a whopping 43% share, helped by the recent sharp fall in coal use. But offshore wind is now really beginning to make its presence felt, with new capacity pushing Q2 output up by a quarter, leaving renewables’ overall share at 35.5% (up from 32% in Q2 2018). The trend is expected to accelerate, with the giant 1.2-GW Hornsea One wind farm now onstream, on top of 2.1 GW in 2018 and 600 MW earlier this year – which will begin to eat into gas demand. Contracts are already in place that would more than double the UK’s 8.5 GW of offshore wind over the next five years and the record low bids in September’s offshore wind contracts for differences (CfD) awards (see below) could encourage still faster expansion.

In a report on offshore wind released in late October, the International Energy Agency (IEA) says offshore wind has “game-changing” potential, and expects costs to fall by 40% by 2030. That is on a par with the cuts in production costs of two other energy revolutions of the past decade – hydraulic fracturing and solar energy. “Looking at the future of offshore wind… it has the potential to join the ranks of shale [gas] and solar photovoltaics in terms of steep cost reductions,” IEA executive director Fatih Birol said. In the past the IEA has been charged with understating the potential for renewables, in its scenarios.

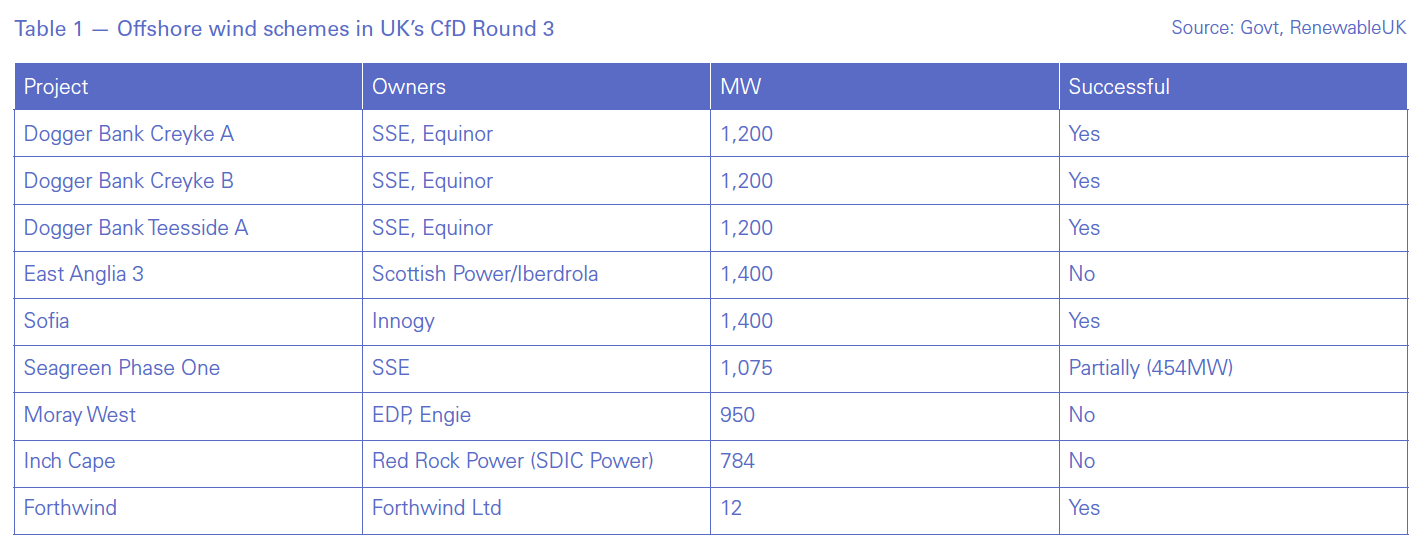

Costs in the UK appear to be falling at least in line with that target, and possibly ahead of the curve. The UK’s latest CfD awards September 20 produced a new UK offshore wind record low of £39.65/MWh -- a 66% cost reduction in less than five years (and 30% down on £57.50/MWh in 2017). A total of six 15-year offshore wind deals were awarded (see table). A portion of one project, Seagreen P1, will even operate at market prices.

Seagreen has a CfD, but only for 41% (454 MW) of its proposed 1075-MW output, and so, if it goes ahead, this would be the first time UK offshore wind capacity has had to rely only on market prices – although there may be potential for term sales at fixed prices close to the CfD bid levels.

There were also four remote island wind farms awards -- the first UK onshore wind since 2016. All 12 projects are due onstream by 2025, although an outstanding judicial review application against the auctions could still scupper the plans. Banks Group called for a Judicial Review on the exclusion of onshore wind from this round, and its impact on the CfDs just awarded. Banks Renewables operates 224 MW of onshore wind capacity and has two consented onshore wind farms in Scotland with a combined capacity of 150 MW that were not allowed to compete.

Offshore wind schemes in UK’s CfD Round 3

Renewable UK said the low bids made offshore wind “significantly cheaper than fossil fuel alternatives.… We are confident we can meet and exceed 30 GW -- the government’s current offshore wind target -- by 2030.” The winning bids were below the government’s own projections of about £48-£51/MWh, and were close to current baseload market prices. The UK baseload spot price for winter 2021/2 was £51.5/MWh and summer 2021 was £45.5/MWh, according to Marex Spectron on October 24, for example.

Among the factors contributing to the low bids were larger turbines and the winning locations’ high wind speeds. Longer term plans envisage wind generation in the area expanding rapidly, making it a key renewable generation centre for northwest Europe. Project extensions are also allowing developers to share costs across projects. Costs were also lowered by more efficient installation procedures and utilities leaning on suppliers to reduce prices, while economies of scale make things cheaper.

Financing costs are being kept down by strong demand for such risk-free low carbon assets, which lowers the cost of debt and equity investments in the projects. For example, in September 140 banks worth $47 trillion pledged to align with the Paris goals. Bidding interest in the next round could benefit from additional competition from European oil majors as well as Equinor as they come under growing pressure from shareholders to show how they plan to align their businesses with global efforts to cut emissions.

The low prices encouraged calls to expand renewable award capacity limits: “Looking beyond this allocation round, we believe the UK government must raise its ambition above 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030. Only by doing so can the country set itself on the right path towards future carbon budgets and meeting the challenge set by government to achieve net zero emissions by 2050,” said Jim Smith, the head of SSE Renewables. Any extra wind will eat into UK gas demand.

German wind problems

The situation is very different in Germany, where the wind focus has been onshore. Here, the outlook for gas demand (and offshore wind) has been buoyed by a dramatic slow-down in onshore wind expansion, with turbine construction falling 82% year-on-year to 287 MW in the first half of 2019. This is the lowest level in nearly two decades, and well below what is needed to meet renewable targets. Gas is also gaining market share from the moves to shut nuclear plants, and lower coal use. Germany's coal plants could lose up to €9bn this year, according to Carbon Tracker.

Most observers put the blame for Germany’s stalled onshore wind sector on a flawed auction design and difficulties in obtaining licences for turbine construction. This has discouraged investors and led to sinking participation volumes and rising prices in Germany’s last five onshore wind tenders – the last, in October, awarded only 204 MW out of the 675 MW on offer, and previous rounds this year had similar results. February awarded the most at 476 MW out of a total of 700 MW.

Auction prices have also been rising, with the last three auctions (August, September and October) all averaging €0.062/kWh, and the two before that (May and February) at €0.061/kWh. This is up on 2018, when May’s award was made at an average price of €0.057/kWh, and down sharply up on 2016, when about 1GW was awarded at just €0.0428/kWh on average (which was about a quarter down on 2015 prices).

German network regulator, BNetzA, said the main factor deterring bidders was the wind-farm permitting process in Germany, which has been getting longer and more likely to incur legal challenges. “The difficult situation regarding approvals for the construction of wind energy plants on land by the responsible state authorities continues to have a decisive influence on the tender procedure and result,” said a BnetzA spokesperson.

Permitting bureaucracy and citizen opposition means the permitting process can now take well over two years, compared with ten months just two years ago, and at least 750 MW of wind farm projects are currently mired in legal proceedings. There is now a total of 11 GW of onshore wind projects stuck at various stages of permitting, according to wind energy trade body, WindEurope.

The latest German award prices are well above the latest UK offshore wind CfDs (at current exchange rates), despite their offshore location and some additional risks and costs in project development and connection. Part of this is down to higher wind speeds and scale, with larger turbines being used; and part down to cheaper finance and lower planning/operational risks, according to Cornwall Insight.

It is hoped that recent policy measures from the German government will address the onshore wind challenges, although there has also been a hike of 5 GW in planned offshore wind. The new measures include new planning rules, a re-targeting of who pays (away from end-users) and higher/more widespread carbon pricing. Utilities are also moving forward themselves. For example, RWE has now adopted a 2040 carbon neutrality target. As well as more wind, the company says it will eventually convert some of its gas CCGTs to burn green hydrogen – further squeezing gas demand, unless methane reformation is employed.