The NOCs hold the trumps [NGW Magazine]

The dramatic collapse of global oil prices on March 8 and the free-fall in global stock markets that followed was precipitated by actions taken by national oil companies (NOCs). Their decision was taken at a difficult time: Covid-19 had already weakened energy demand.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) distinguishes between NOCs that concentrate on domestic production and international NOCs (INOCs) that have both domestic and significant international operations. But both kinds wield disproportionate power well beyond the borders of their countries, through their influence on the oil price.

According to IEA, NOCs include the largest companies both in terms of production and in terms of reserves size. They have mandates from their home-country governments to develop national resources, with a legally defined role in upstream development.

These include Saudi Aramco, Qatar Petroleum, the National Iranian Oil Company, Rosneft, Azerbaijan’s Socar, Petrobras, Pemex, Nigerian National Petroleum Company and Algeria’s Sonatrach. Into the latter category fall China’s trio of CNPC, CNOOC and Sinopec; Norway’s Equinor; Russian Gazprom; India’s ONGC; and Malaysia’s Petronas.

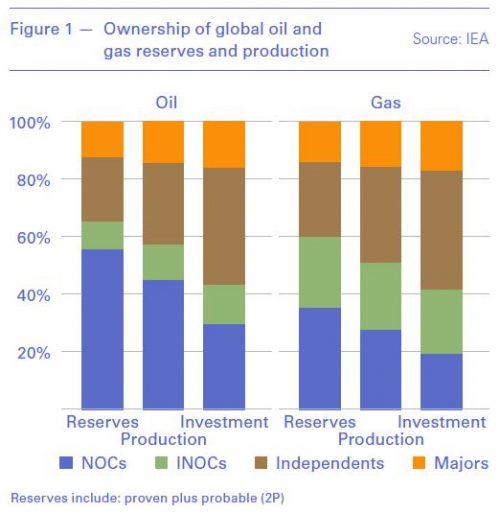

Between them, NOCs and INOCs own almost two-thirds of global oil reserves and 57% of oil production, 60% of global gas reserves and over 50% of gas production (Figure 1).

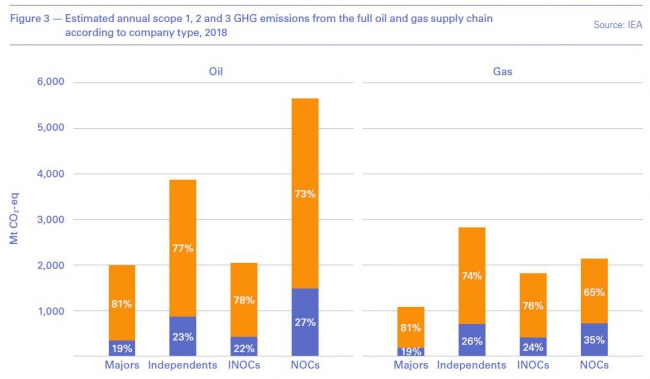

Oddly, the majors, which attract so much attention from the environmental lobby groups, account for only 12% of oil and gas reserves, 14% of production and are responsible for 10% of the estimated emissions from industry operations.

As the IEA points out, it is important to note that NOCs control not only by far the largest portion of reserves, but also those with the lowest average development and production costs. In addition, many of their assets have slow decline rates, meaning that they can maintain production at relatively low costs (Figure 1).

Their governments therefore wield immense power over the scale of future oil and gas production, refined products and petrochemicals, just as the majors face growing pressure from lenders and shareholders to move their focus outside the oil and gas sector.

With many NOCs moving downstream, most of the new refinery and petrochemicals capacities that are planned will be in the Middle East and in developing countries in Asia. The exception is perhaps the US, where cheap natural gas is feeding the development of petrochemical plants. Major producer ExxonMobil for example is planning to add value to its ultra-low-cost gas by turning it into feedstock to make competitively-priced plastics.

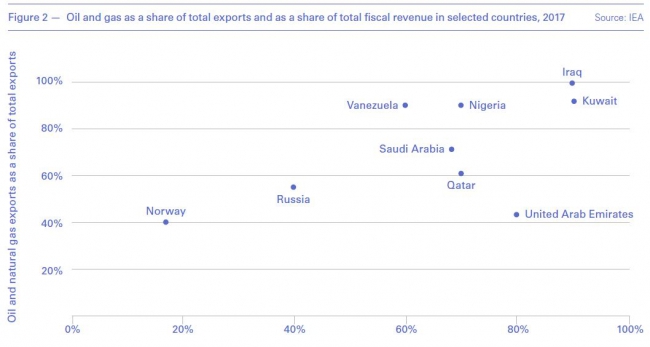

The energy transition is raising the stakes both for NOCs and INOCs and their home countries. However, high dependence on oil and gas export revenues can be a strategic vulnerability for resource-rich economies, as the current oil price collapse vividly demonstrates. Those countries that rely heavily on oil income become highly vulnerable when the oil price collapses. In such situations the opacity of NOCs and INOCs can pose additional fiscal governance risks.

Pivotal role

As the IEA states, the pivotal role of NOCs and INOCs in the oil and gas sector is sometimes overlooked. The mandates given to NOCs by their home countries give them privileged positions in their domestic energy sectors, and not having public shareholders makes many of them largely immune to international environmental activism – unlike the IOCs.

National priorities play an important role in determining NOC investment strategies. Many in the Middle East are raising upstream activity to sustain oil production and meet growing domestic natural gas needs. Investment by Chinese NOCs has also soared over the past two years in response to a government mandate to increase production.

With the IEA stating that investment in oil and gas projects will still be needed even in a rapid transition to clean energy, low production cost NOCs and INOCs will have a role to play well into the future.

However, in recent years structural vulnerabilities have become apparent not only in some NOCs and INOCs, but also in the economies of their home-countries, especially where there is high dependence on oil export revenue (Figure 2).

Not fully understood

NOCs are mostly poorly understood, remaining largely opaque because of their often limited financial and performance reporting and governance. It is not always easy to distinguish corporate from national imperatives.

They key messages from a study of NOCs published in 2019 were:

- NOCs produce the majority of the world’s oil and gas. They dominate the production landscape in some of the world’s most oil-rich countries – including Saudi Arabia, Mexico, Venezuela and Iran – and play a central role in the oil and gas sector in many emerging producers. In 2017, NOCs that published data on their assets reported combined assets of $3.1 trillion.

- At least 25 countries are ‘NOC-dependent’, meaning that the NOC collects revenues equivalent to more than a fifth of all government revenues. The fiscal health of many countries – and governments’ ability to use oil revenues to finance development – depends heavily on how well the NOC is run, how much revenue it is required to transfer to the state, and the quality of its spending.

- Many NOCs carry big debts, sometimes as much as 10% or even 20% of their countries’ GDP. Several NOCs have required multi-billion-dollar government bailouts in recent years, becoming a costly drain on public finances.

- About 62% of NOCs exhibit ‘weak’, ‘poor’ or ‘failing’ performance on public transparency, as measured by the Resource Governance Index.

The study found major shortcomings in NOC transparency, with many companies failing to report critical information necessary for oversight, making it difficult for citizens to scrutinise their management of public resources (Table 1) – factors that in quite a few cases contribute to large-scale corruption.

The study recommends that “the combination of strong reporting and a vigorous system for oversight is critical to ensure that these companies maximise their incentives to perform effectively in the public interest.” This can happen only by home-country governments having the will to implement appropriate policies.

The good news is that the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) launched last year a new standard committing its 52 member countries to “systematic disclosure of extractives data as a default” and it also “contains new requirements on contract transparency, the environment and gender.” In addition, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has released new “Anti-Corruption and Integrity Guidelines for State-Owned Enterprises,” complementing its guidelines on corporate governance.

On the positive side, in many countries, NOCs employ some of the best-educated professionals and bring experience managing complicated projects with international partners. As a result, they may be the natural partners to drive an expansion into clean energy.

However, as the study concluded, “The size of the rents available in fossil fuels, the bespoke skills and technologies involved in the sector, and the entrenched political interests associated with oil all pose obstacles to NOC efforts to transform.”

And transformation is becoming urgent: they need an alternative to fossil fuel dependence as those assets risk being stranded.

Better reporting and separating public relations from reality in NOC pronouncements are key. Boosting commercial efficiency – and overcoming corruption – requires consistent and transparent reporting and oversight on spending, production costs, and revenues.

Role in oil price collapse

The collapse in global oil prices and the stock market in early March was momentous. It happened because of two largely unconnected shocks interacting in a devastating manner. One is the Covid-19 pandemic, which had been ongoing since a least the start of the year, impacting global oil and gas demand.

The other was the dramatic breakdown of Opec+ negotiations to shore up the oil price in early March. Russia refused to back a plan by Opec to cut oil production by 1.5mn b/day in April, leading to a ‘free-for-all’ in oil production.

Either on its own would have impacted global oil and stock markets, but their combined effect was devastating. Brent crude fell to $25/b and the Dow Jones index fell by 7.8%. Brent had started the year at around $70/b.

The NOCs, Saudi Aramco and Rosneft – and their countries – were the root-causes of the rift. There is an underlying suspicion that both sensed an opportunity to put the already highly indebted US shale industry under distress and force bankruptcies and a reduction in shale oil production.

This is because, so far, every time Opec+ agreed to production cuts, US shale oil stepped-in to cover demand, undermining and negating Opec+ actions to shore up the oil price. Russia believes that output cuts only subsidise the US shale industry. US sanctions may also be another factor.

Nevertheless, their actions have had a devastating effect on global oil and gas markets and the global economy at a time of great vulnerability.

If no agreement is reached soon – combined with Covid-19 impacting global oil and gas demand further – the consequences of this price war could be longer-lasting. Oil storage facilities are already almost full. In the US this is likely to lead to a massive wave of bankruptcies.

Impact of oil price collapse

As the IEA points out, major swings in oil and gas revenue can be deeply destabilising if the finances and economies of NOC-owning countries are not resilient. This is exactly the risk now as a result of the Saudi Arabia-Russia oil price war.

IEA boss Fatih Birol, said that countries such as Ecuador, Iraq and Nigeria would be particularly hard hit by the oil price slump, adding that “If prices remain at these levels — around $30/bl — we see the income for the vulnerable producer countries will fall by between 50% and 85%” (Figure 2). He warned that collectively the most vulnerable oil producers may be facing very low revenues indeed. He added that “International financial institutions may need to step in and take special measures.”

Birol has been critical of oil producing countries, saying that they are playing “Russian roulette” with markets at a time of uncertainty and vulnerability for the world economy. He added that the apparent price war is an attempt to "kill" the US shale sector, but this is unlikely to succeed. But there is no doubt that indebted US shale oil producers are being hit the hardest by such a price war.

Energy transition and emissions

For many NOCs and INOCs, and their countries, there is a clear risk that some of their larger underlying resource holdings could become stranded in energy transition. As a result, the focus in some of these countries is on reducing reliance on hydrocarbon income while also looking for ways to monetise these resources faster.

Al least up to now, none of the large NOCs has been charged by their home-country governments with leadership roles in renewables or other non-core areas.

The pressure from home-country governments for high fiscal returns conflicts with the high investments and low returns characteristic of renewables. What may be needed to drive transition is new green legislation, the removal of fossil fuel subsidies, and new targets for clean energy and emissions. But these are not receiving high priority in most countries with high reliance on NOC-generated income – priority remains the development of national oil and gas resources.

Nevertheless, NOCs and INOCs understand that doing nothing is no longer an option. The IEA states that the most forward-looking NOCs are accelerating research efforts in decarbonisation. These cover a range of areas, including carbon capture, use and storage, hydrogen, and strategies to find and develop non-combustion uses for hydrocarbons. But NOCs and INOCs are still slow in embracing decarbonisation.

NOCs and INOCs are responsible for an estimated 53% of all oil and gas related Type 1, 2 and 3 emissions - 57% of oil and 47% of gas-related emissions (Figure 3).

The future

The oil price collapse of 2014 to 2015 proved a blessing for the oil and gas industry. It forced companies to cut operating costs and direct investment towards easier and faster to develop projects with high returns. Something similar may happen now. With more cost-cutting and the resulting realignment though the survival of the fitter companies, the oil and gas industry could emerge stronger and even more competitive, with lower break-evens.

The pressure will be more on majors and independents. NOCs and INOCs such as Saudi Aramco and Rosneft are better shielded, although in the medium term they need a healthy global economy to sell their oil and gas.

As producing countries grapple with reduced revenues, channelling investments into renewables will become even more challenging. This includes reform and economic diversification, which, even though essential, may be put on the back-burner.

NOCs and INOCs are increasingly becoming the ‘fuel’ providers to the world – particularly the developing world – reaping the benefits but not yet contributing to the energy transition. Increasingly, though, the pressure from the rest of the world will be to reduce carbon intensity, embrace cleaner energy and increase transparency, disclosure and oversight. But the gradual polarisation of the world in terms of clean energy, with advanced economies pulling in one direction and developing economies in another, means that this will prove a challenge in the short to mid-term.