The future of natural gas in a low-carbon world: GECF and Shell present divergent pathways [Gas in Transition]

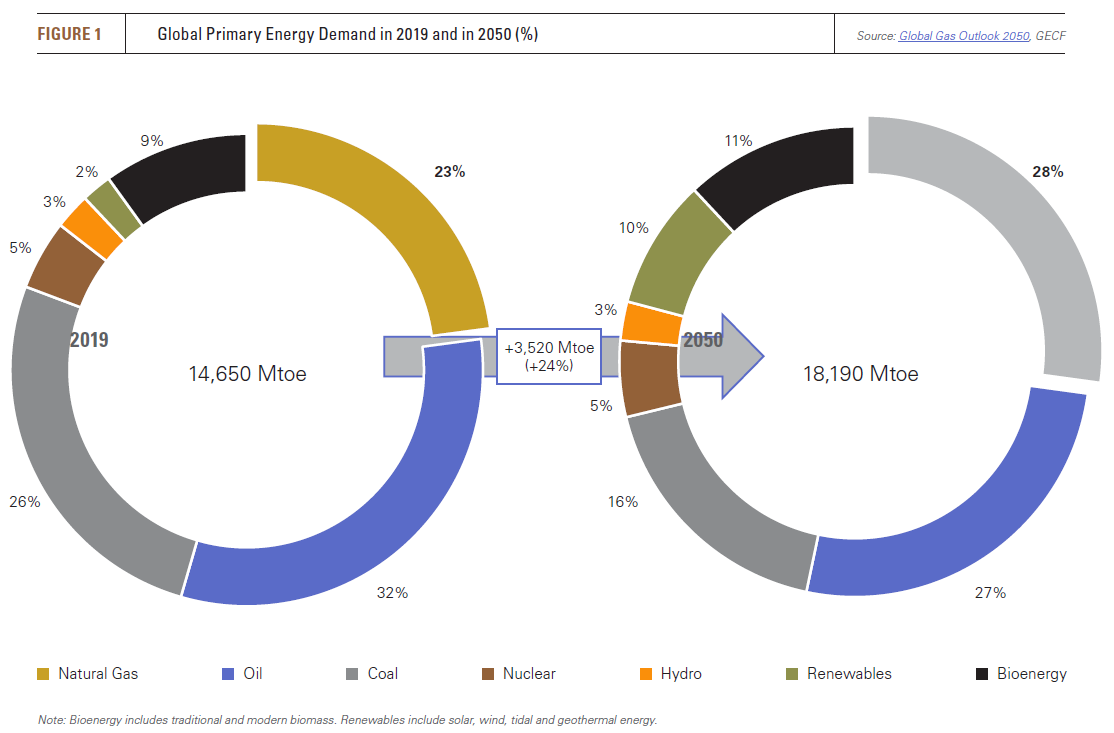

It is no surprise perhaps that the Gas Exporting Countries’ Forum (GECF), being in the business of selling gas, presents a highly optimistic picture for the future of its product. According to the GECF’s Global Gas Outlook 2050, published in February, natural gas will be the largest single source of energy demand in 2050, with a 28% share in the energy mix (compared to 23% today), surpassing oil and coal.

In the GECF scenario, renewables (Figure 1) will account for just 10% of global primary energy demand and bioenergy 11%.

According to the GECF, natural gas will be responsible for 48% of energy demand growth over the next three decades. “Rising levels of consumption in the power generation, industry and transport sectors will enhance the position of this fuel across all the regions.”

As to climate constraints, the GECF does not see any. “When it comes to climate change goals, natural gas has won the ‘battle’ and embedded itself into all the important discussions, from the G20 to the UNFCCC, and from BRICS to the World Economic Forum,” writes Secretary-General Yuri Sentyurin in the foreword.

The GECF does consider an “alternative carbon mitigation scenario” in the annex to the report, but that too sees gas demand rise. This scenario “highlights a considerable carbon mitigation potential for natural gas, with reinforced policy actions and technological progress. Further innovation and development of decarbonisation technologies, such as CCUS and hydrogen, can substantially improve this mitigation potential.”

Hydrogen and renewables take second place

The GECF report does not have much to say on hydrogen, except that it believes “more than half” of the hydrogen needed by 2050 will be based on natural gas. “Although upscaling the contribution of hydrogen requires significant technical progress and cost reduction, there is a non-negligible potential stemming from gas-based hydrogen paired with CCUS,” writes Sentyurin.

The GECF sees renewables demand rise along with gas demand: “The energy transition is underway, and natural gas together with renewables will gain in importance and will be the major contributors to incremental growth in global energy demand, together accounting for more than 90% of the additional 3,520 Mtoe through to 2050.”

But renewables will take second place. The renewables revolution is about to experience some bumps in the road, says the GECF: “Renewables ambitions are revised upward in several countries, but renewables expansion will face some policy headwinds, including the shift to market-based support schemes, supply chain barriers, and the integration issue. These challenges contribute to driving a mismatch between the stated targets and ambitions.”

Shell is much less optimistic

Shell also published new scenarios in February of this year, including for the first time one that is based on a 1.5°C temperature rise by 2100. ThisSky 1.5 scenario is much less optimistic about the future of natural gas than the GECF’s Global Gas Outlook.

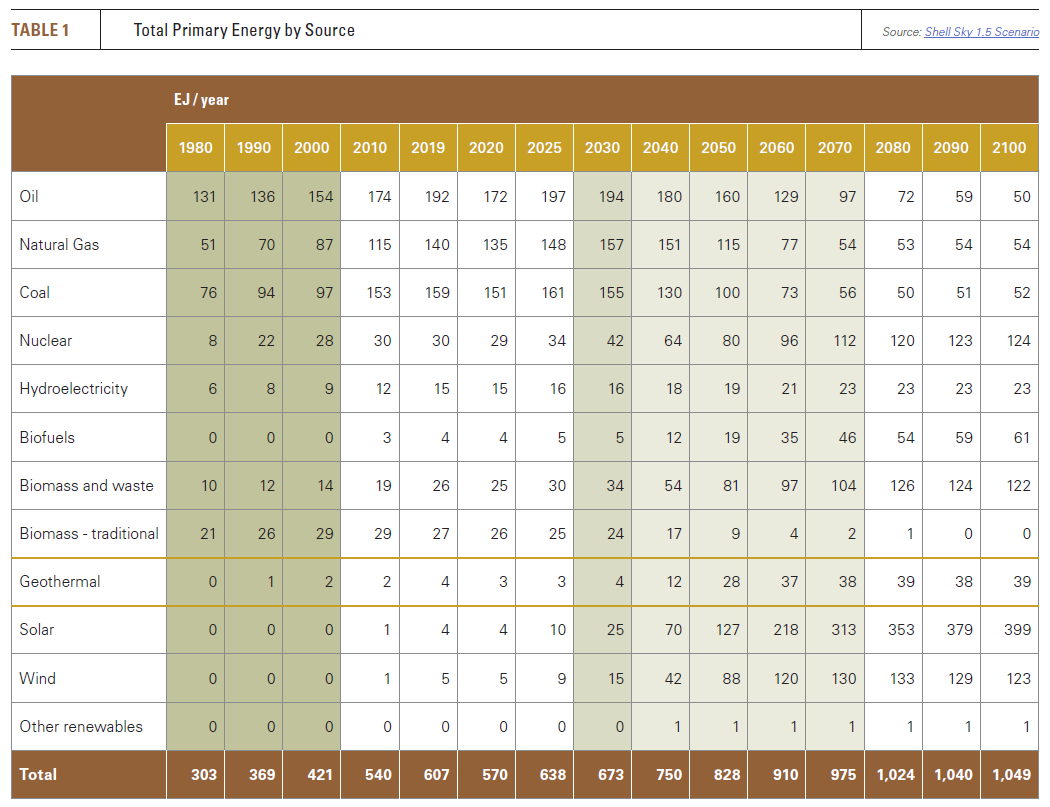

In Sky 1.5, oil is still the largest single source of primary energy (Table 1) in 2050 (19.3%), followed by solar power, with gas in third place, barely ahead of bioenergy. Solar and wind together represent 26% of total energy demand in 2050 and natural gas just 13.8%, which is half of what the GECF expects.

Looking further ahead, to 2100, the share of natural gas has shrunk to just 5% in the Sky 1.5 scenario, with solar power good for a massive 38%, even as total energy demand has continued to expand. Interestingly, nuclear power, biomass and wind power have each become bigger than oil, gas and coal.

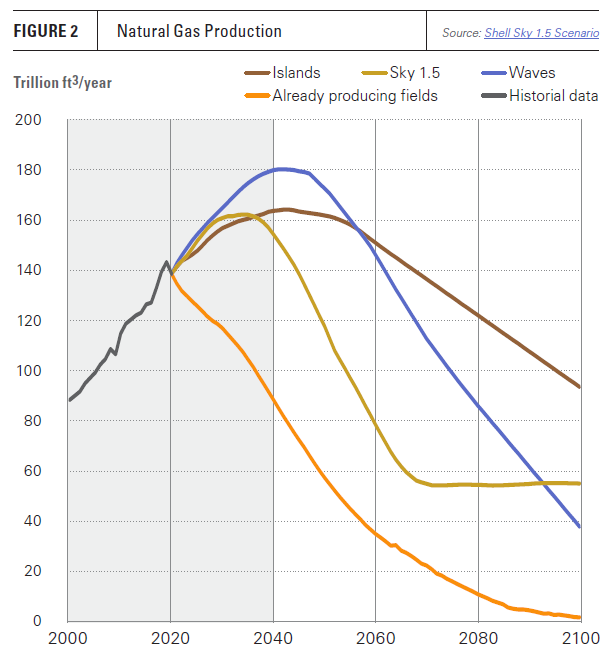

Sky 1.5 sees natural gas still grow for the next decade (Figure 2), with a peak expected in 2034, followed by an abrupt decline. Continued investment in gas production will be needed in the first period.

It is difficult of course to assess the likelihood of either scenario coming to pass. Much will depend on the choices made by policymakers, investors and consumers.

It is worth pointing out that Shell’s Sky 1.5 scenario depends heavily on carbon removal efforts, which is not immediately apparent from the graphs. For one thing, as the Shell authors note, it “requires major reforestation – some 700mn hectares of land would be required over the century, an area approaching that of Brazil.”

In addition, the Sky 1.5 scenario assumes a major CCS effort. Together, natural carbon removal and CCS account for approximately half the required emission reductions in the Shell scenario.

Big choices for Big Oil

The future, then, is uncertain – but we already knew that. From a European perspective, the GECF scenario is definitely not what policymakers are envisioning. But other continents have different concerns and there is truth to the GECF’s assessment that the expansion of renewables will encounter obstacles, such as lack of space, public resistance and variability limits.

Hydrogen is now viewed as an almost magical solution in Europe, but many are beginning to have second thoughts (see elsewhere in this issue). In addition, the role of bio-energy is surrounded by question marks. In Shell’s Sky 1.5 scenario, biomass and biofuels together will provide almost as much energy as oil does today, which is quite a proposition.

How should energy companies deal with these uncertainties? According to a recent report from consultancy McKinsey, The big choices for oil and gas in navigating the energy transition, companies essentially have three choices: they can choose to “build a more resilient core business”, they can “explore profitable growth options in low-carbon businesses”, or do both. What they should do in any case is to “change their operating models to increase competitive edge”.

Continuing with business as usual is not a good idea, according to McKinsey. The report notes that over the past 15 years, annual total returns to shareholders for the average oil and gas company have lagged the S&P 500 by seven percentage points. “This suggests the sector’s traditional business model has been under stress for some time now. Our research shows that over the same period, global capital investment by the sector has amounted to more than $10 trillion in real terms. In practice, cyclical-sector overinvestment has made it harder to earn a productive return than was previously the case.”

The solution for companies that want to stick to gas and oil, says McKinsey, is “to build a portfolio that is resilient to both lower commodity prices and higher carbon prices.” So-called “advantaged” resources “offer the best combination of lower break-even prices and lower emissions intensity”. In other words: go for shallow water and conventional resources, skip deepwater and oil sands. “High-grading the carbon portfolio” is how McKinsey describes this – fairly obvious – strategy.

Low-carbon pure plays offer plenty of opportunities

Oil and gas companies could also shift entirely to “low-carbon pure plays”. Several medium-sized companies, such as Neste and Orsted, have made this choice.

How much growth potential do low-carbon technologies – renewable power, electrification, bioenergy, hydrogen, CCUS, negative emissions technologies, carbon trading – offer? Quite a bit, according to McKinsey. A 1.5°C scenario, says the report, requires five times more wind installations, eight times more solar installations, nine times more EV sales, three times more bioenergy, 1.7 times more hydrogen, 50 times more CCUS and 15 times more carbon offsets – all by 2030.

Oil and gas companies taking this route will encounter stiff competition, though, from the likes of Enel, Iberdrola and NextEra – utilities that have already made the switch to low-carbon energy. They are called the “new green energy giants” by the Wall Street Journal. The combined capitalisations of these companies has grown from $110bn to $300bn in ten years, whereas BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil and Shell have seen their capitalisation shrink by 40% from $980bn to $570bn over the same period, observes McKinsey.

Oil and gas companies have plenty of capabilities

The large European oil companies, such as BP, Total, and Shell, have made the choice to remain integrated energy players, betting both on retaining “their profitable core” and expanding into new low-carbon markets. There are challenges to this strategy, notes McKinsey. “Oil and gas titans have an abundance of capabilities that may be valuable for parts of a new low-carbon energy system”, but “they need to consider where they are best suited to compete in various low-carbon energy arenas.”

After having made their choices, “they need to reimagine their longstanding operating models and forge new capabilities, leadership and cultures to enable these new businesses to grow under their ownership.”

According to McKinsey, oil and gas companies have plenty of capabilities to enable them to become successful in these new markets. Nevertheless, the McKinsey consultants note that “winning in new arenas requires building an agile, attacker mindset”, and they raise the question of whether investors propositions can be created in which “the value of both old and new businesses is fully reflected in the share price.”

Should Big Oil spin off their renewables businesses?

According to independent financial energy consultant Gerard Reid, the answer is that such businesses had better be separated to fully exploit their value. In article written with Andrew Symes, Why Big Oil needs to consider spinning off their renewables and new-energy businesses, he notes that not only did Big Oil stocks do much worse over the past five years than renewables companies, but the worst performing oil and gas stocks were those companies that were most aggressive about decarbonisation, namely Total, Shell, BP, Eni and Repsol (all European).

The problem, says Reid, is that “renewable and oil & gas businesses are likely to be valued completely differently”. They have entirely different risk factors. Most investors, he notes, “want to invest in ‘pure play’ companies as it allows them to better manage their own risk.”

“Some investors will not want the higher risk exposure to oil & gas and hence will invest in renewables-focused companies such as Iberdrola,” write Reid and Symes. “In contrast, some investors, realising the continued importance of oil & gas for at least the next two decades, will want exposure to the upside potential of the oil & gas business; but will place little value on the contributions from the renewables business until they are large enough to act as a true hedge to the risks related to the fossil-fuel investment.”

The solution, Reid and Symes write, is for oil and gas companies to be split into two distinct businesses, “a low-return growth business focused on renewables and electrification and an oil & gas business focused on cash generation from the highest value oil & gas projects, as well as transition technologies such as carbon sequestration and blue hydrogen projects.”This problem “is compounded by the recent rise in ESG [environmental, social and governance, ie, socially responsible] investing, which increasingly prohibits significant numbers of investors from taking any exposure to oil and gas at all.”

The legacy business “would still maintain exposure to renewables and new energy through its shareholding in it,” they suggest. “In fact, it could alter this shareholding over time by investing or divesting in it as a source of liquidity.”

An additional advantage is “that it would allow two different cultures and brands to emerge better suited to the different business models and customers.”