Southern cone gas threatens LNG imports [Gas in Transition}

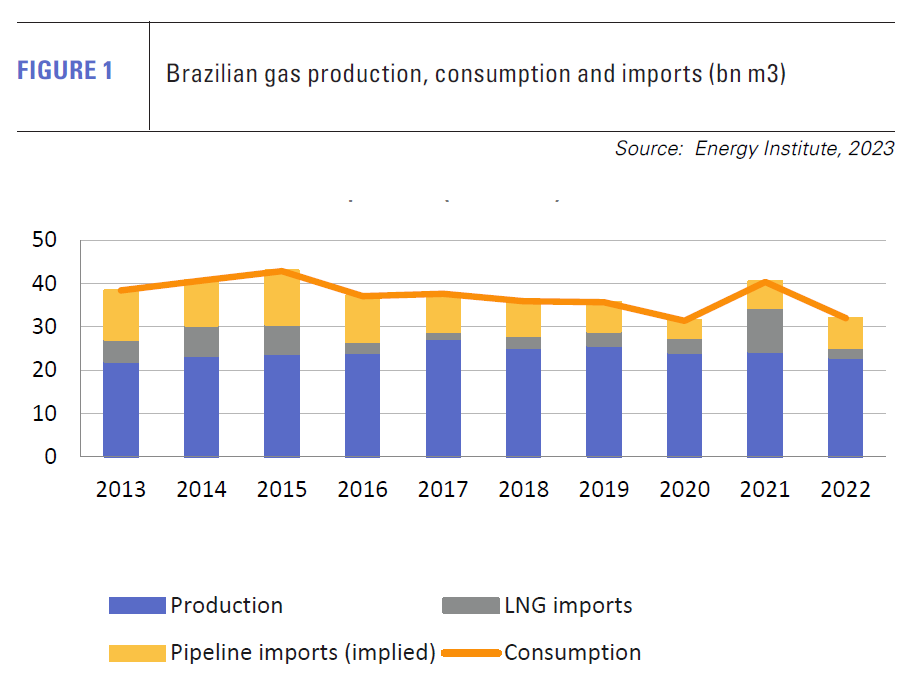

LNG import capacity is growing in Brazil, despite a changing gas balance in the southern cone and a large surplus of regasification capacity in the country itself. In 2022, Brazil imported just 2.3bn m3 of LNG down from 10.1bn m3 in 2021 (see figure 1), when drought reduced hydro generation levels, requiring more gas to be imported for power generation. Yet the country has more than 35bn m3/yr of LNG import capacity spread across six facilities with three more under construction.

A combination of growing renewable energy capacity, domestic gas production and potential imports from Argentina look likely to be disruptive for LNG. However, some companies take the view that Brazil’s large size, limited gas pipeline infrastructure and need for dispatchable generation to back up its heavy dependence on hydro power create opportunities for the flexible fuel. In particular, Brazilian electricity demand shows much stronger growth than its neighbours, increasing the need for flexible gas-fired generation, some of which will be powered by LNG.

New terminals

Terminal Gas Sul in Santa Catarina state is expected to start commercial operations as early as this month. Operator New Fortress Energy (NFE) announced in November that it had signed a deal to charter the Energos Winter, a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU), from Brazil's state oil and gas company Petrobras starting in December 2023. Terminal Gas Sul is connected to the gas pipeline system in southern Brazil, providing access to the country’s main centres of demand.

In the far north, in Para state, which borders Suriname, NFE is also making progress with its Barcarena LNG import terminal. In November, the facility was slated to start operations by the end of 2023. NFE announced in November that it had closed financing on completion of the 630-MW Barcarena power plant, which is adjacent to the import terminal. The plant was reported to be 37% complete and is expected to be operational in third-quarter 2025.

Unlike the Santa Caterina terminal, Barcarena is far from Brazil’s main gas demand centres and NFE will initially provide regasified LNG to Norsk Hydro’s Alunorte alumina refinery under a 15-year supply agreement signed in 2021. It will also supply gas to utility Gás do Pará, which will distribute it to local industry. In future, Gás do Pará plans to provide gas for commercial and residential use as well as for land transport.

Domestic gas supply

At a country level, Brazil has far more LNG capacity than it needs. Moreover, marketable Brazilian gas supply should more than double over the next decade.

Bringing gas from the country’s large offshore pre-salt oil finds has been a long-standing aim but has proved neither easy nor quick. Not only does the gas have competing uses – primarily for oilfield reinjection – but long offshore pipelines have to be built in deep waters to bring it to shore. Pre-salt gas also has a high CO2 content, which increases gas processing costs.

Two major pipelines, Rota 1 and 2, have been completed. Rota 1 has a capacity of 3.65bn m3/yr and started operations in 2011, connecting the offshore Tupi oil and gas field with Sao Paulo state. Rota 2 came onstream in 2016. It also originates from the Tupi field, but passes through the Búzios oil and gas field before landing at the Cabiúnas Gas Treatment Terminal in Macaé, Rio de Janeiro state.

The big change coming is the completion of Rota 3, which is expected in the second half of this year. The pipeline will have a capacity of 6.57bn m3/yr and the gas will land in Rio de Janeiro state to be processed at the Gaslub complex, in Itaboraí. Combined, the Rota 1-3 pipelines will have flow capacity of about 44mn m3/d, equivalent to 16bn m3/yr.

Construction of the Rota 4,5 and 6 pipelines is more uncertain and continues to be a subject of heated debate, but two other projects look likely to boost Brazil’s gas supply in coming years.

In September, Norway’s Equinor chose Tenaris to supply 83,000 tonnes of welded line pipe and tubular accessories for the gas export line of the BMC-33 block. Production is expected to start in 2028 from three pre-salt discoveries holding reserves of more than 1bn barrels of oil equivalent. The gas will be processed offshore on a floating production, storage and offloading (FPSO) vessel and exported through a 200-km export pipeline (BM-C-33) to Cabiúnas, in the city of Macaé. The pipeline will have a capacity of 5.84bn m3/yr.

The second major project is Petrobras’ SEAP, which will also use FPSOs to process the gas offshore. Tenders for the two vessels are expected to be announced this month, following the date being pushed back by two and half months last year. In its Strategic Plan 2024-2028, the first released under the new presidency of Lula da Silva, the company plans to invest $7bn to increase gas production and transmission from its exploration and production segment. The SEAP project is based on gas production from the Sergipe Águas Profundas pre-salt area and is expected to have a capacity of 6.57bn m3/yr starting in 2029.

As a result, according to projections by the Brazilian Institute of Oil & Gas, marketable gas production will rise from 18.6bn m3/yr in 2023 to 48.9bn m3/yr in 2032. This compares with average annual gas consumption from 2013-2022 of 37.2bn m3/yr backed by average annual LNG imports of 4.5bn m3. Both gas consumption and LNG imports are heavily affected by hydro generation, which accounted for just over 60% of the country’s electricity generation in 2022.

In 2022, Brazil produced 50.4bn m3 of gas, but marketable supply was only 17.4bn m3, after gas reinjection and E&P consumption.

Bolivian pipeline imports

Brazil currently imports gas by pipeline from Bolivia but supplies along the 3,150-km GasBol pipeline have fallen sharply. The pipeline, which has capacity of 11bn m3/yr, enters Brazil in Rio Grande do Sul state in the country’s southeast and runs through the states of Mato Grosso do Sul, São Paulo, Paraná, and Santa Catarina.

Supplies through the pipeline in July last year were just 13mn m3/d and totalled 6.1bn m3 in 2022. In September, Bolivian President Luis Arce announced that the country’s natural gas reserves were depleted, and exports to Argentina and Brazil would be interrupted.

In January last year, consultants Wood Mackenzie forecast that increasing domestic demand in Bolivia would outstrip production by 2030, but Arce’s comment suggests the situation could be even worse. Bolivian gas exports to Argentina are expected to end in the middle of this year, two years earlier than contracted.

Vaca Muerta ramps up production

The hole left in Brazil’s gas balance from the loss of Bolivian imports could be more than filled by Argentina. However, in the first instance Argentina needs to address the problems created by its own loss of Bolivian gas, which is crucial for energy supply in its northern states during the southern hemisphere winter (June-August).

A project to reverse the direction of pipeline flows from north-south to south-north to access gas from Argentina’s Vaca Muerta shale gas deposit has become a top priority. Using a $540mn loan from the Development Bank for Latin America and the Caribbean to cover much of the $710mn cost, a new 122 km, 36-inch pipeline is being built between the towns of Tío Pujio and La Carlota as well as two loops of 62 km.

The direction of gas injection will be reversed in four existing compressor plants in Córdoba, Santiago del Estero and Salta to engineer the reversal of the Northern Gas Pipeline. This will allow Vaca Muerta gas to flow to Córdoba, Tucumán, La Rioja, Catamarca, Santiago del Estero, Salta and Jujuy. It should also facilitate the future connection of commercial, residential and industrial gas users, as well make possible the export of gas to the centre of Brazil and Bolivia, as well as to northern Chile, where the Mejillones LNG terminal is located.

Other options for exporting Vaca Muerta gas to Brazil include building a new pipeline through Uruguayana, via Potro Alegre, to reach the industrial Sao Paulo area. The investment costs would be larger than using the existing infrastructure through Bolivia, but it would avoid the potential difficulties of having to negotiate supply and transmission agreements between three countries.

Increases in gas supply from Vaca Muerta have already allowed the country to firm up its exports to Chile through existing pipelines. In September, Argentina authorised an increase in gas export volumes to Chile of 4mn m3/d to 9mn m3/d for the period October-December 2024, with the GasAndes pipeline being the principal route, which delivers gas to central Chile.

Increases in gas supply from Vaca Muerta have already allowed the country to firm up its exports to Chile through existing pipelines. In September, Argentina authorised an increase in gas export volumes to Chile of 4mn m3/d to 9mn m3/d for the period October-December 2024, with the GasAndes pipeline being the principal route, which delivers gas to central Chile.

Vaca Muerta continues to go from strength to strength. Completion in August last year of the Néstor Kirchner Gas Pipeline, connecting Neuquén province, with Buenos Aires, was a key step forward. The pipeline has a capacity of 24mn m3/d, but flows are limited to less than half at present, owing to the need to install and complete compressor stations.

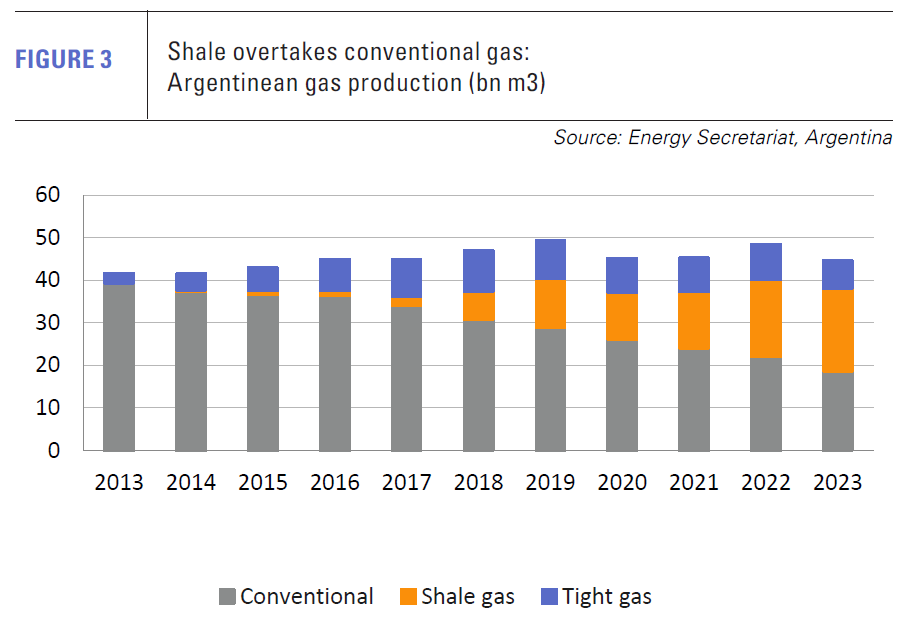

Increased output from Vaca Muerta is expected to result in a forecast rise in Argentinian gas production of about 10% next year, according to ratings agency Fitch.

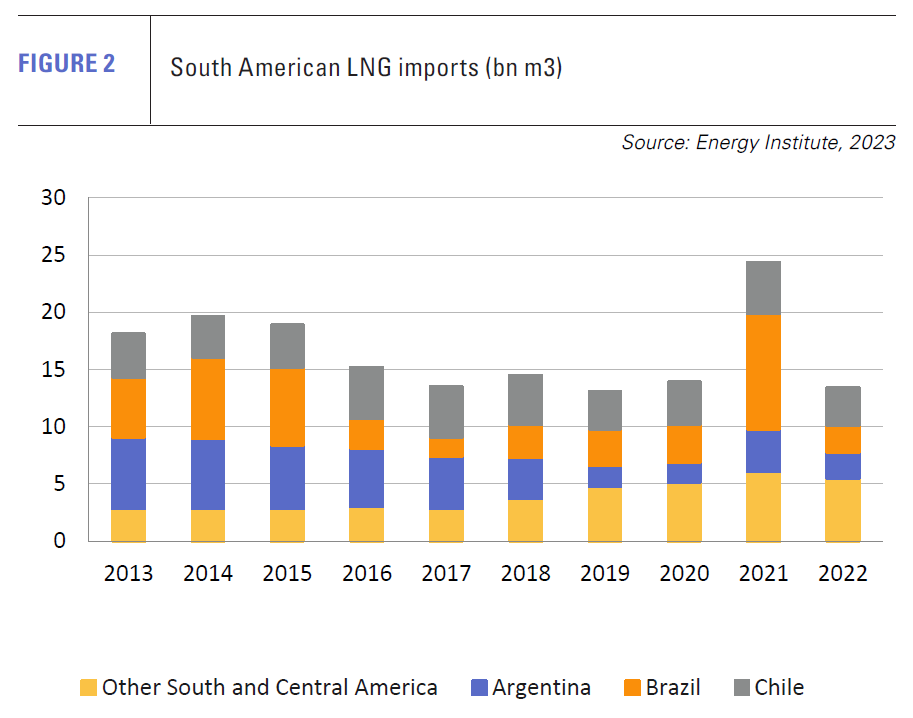

Construction of the Néstor Kirchner Pipeline Stage 2 will add a further 20-25mn m3/d takeaway capacity and could be complete by the end of 2024 or early 2025. Combined with the ramping up of flows through Stage 1 and the reversal of the Northern Gas Pipeline, Argentina will have gone a long way towards positioning itself as a regional gas exporter, displacing LNG imports for its own consumption, and potentially in Chile and Brazil as well (see figure 2).

Pan American CEO, Marcos Bulgheroni estimates that Argentina could export up to 75mn m3/d to Brazil (40mn m3/d), Chile (20mn m3/d) and Uruguay (15mn m3/d) from Vaca Muerta once the mid-stream infrastructure is in place, as well as exporting gas to Bolivia and Paraguay.

To date the expansion of shale and tight gas production from Vaca Muerta has only just kept pace with the decline in Argentina’s conventional gas production (see figure 3), but the construction of new gas transmission infrastructure could see production volumes surge.

There is the possibility that Argentina chooses to focus on LNG exports. The LNG promotion bill was approved by the lower house of Congress in October, but the focus currently appears to be on the opportunities provided by regional pipeline exports using existing infrastructure.

LNG outlook

A combination of increased pre-salt gas volumes and Argentinian imports, notwithstanding the loss of Bolivian gas, appears to place Brazil’s LNG import capacity at high risk of under-utilisation, or at best significant price competition.

Far in the north, away from the pipeline delivery points of both Brazilian offshore pre-salt gas and Argentinian piped gas, LNG remains a competitive option, but further south in the industrial areas of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, the market is likely to prove more challenging in coming years.

LNG importers appear to be pinning their bets on strong electricity demand growth and the need for gas-fired generation to stabilise Brazil’s hydro-heavy electricity system, which also has a growing volume of variable wind and solar generation. Brazilian solar PV capacity jumped by almost 10 GW in 2022 to just over 24 GW, while its wind capacity increased by 3 GW also to just over 24 GW, according to Energy Institute data.

Projections for electricity demand growth remain strong. Brazil’s national grid operator ONS forecasts an increase in electricity demand of 3.5% this year and 3.2% on average each year until 2028. Peaks in electricity demand are also becoming higher, breaking new records in November last year. Support for gas demand is also expected from industry and from land transport. Nonetheless, just as shale transformed the US gas landscape, Vaca Muerta may prove the Achilles heel of LNG imports into South America’s largest economies.