Southeast Asia and the next gas boom [NGW Magazine]

Late last year, the Asean Centre for Energy (ACE) published its 6th Energy Outlook (AEO 6) covering the period to 2040. It was prepared with support from the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit.

It fills out and builds on the strategies of the Asean Plan of Action for Energy Co-operation’ (APAEC) Phase II: 2021 to 2025. APAEC was approved by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in November 2020.

Introducing AEO 6, the head of ACE Nuki Agya Utama said that following the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, ”the complexity of the situation is further heightened by the need to achieve multiple policy aims at once, on energy and other priorities. The energy policy choices made by each Asean member state (AMS) will not only determine the sustainability of these countries’ economies, but also have implications for the region and the world.” Key to these choices are: energy security, accessibility, affordability and sustainability.

Asean has 10 members: Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. They are home to about 650mn people, with a combined gross domestic product (GDP) of $9.34 trillion in 2019.

Even after accounting for the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the region’s GDP is projected to nearly triple by 2040, while its population is expected to rise by a fifth and income per capita going up 250%, implying a massive growth in living standards. Fuelling that growth will require significant amounts of all forms of energy.

Together with east and south Asia, comprising what is known as the Asia-Pacific region, they consume, with their major manufacturing centres, close to 45% of global primary energy. But more importantly, with primary energy demand falling in Europe and the Americas, this wider region accounts for much of the world’s growing energy demand.

As with the Asia-Pacific region as a whole, Asean still depends heavily on fossil fuels for energy, even though there has been a strong commitment towards sustainable energy. Asean’s short-term target is to achieve a 23% share of renewable energy in the total primary energy supply and a 32% reduction in energy intensity by 2025 in comparison with 2005 levels.

ACE investigated four different scenarios but they exclude net-zero or rapid transition options.

- Baseline scenario: based on ‘business as usual’;

- AMS targets scenario (ATS): based on each member meeting its own climate commitments;

- APAEC targets scenario (APS);

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDG): what AMS would have to do to achieve the three targets of UN SDG 7 by 2030, namely: ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services; increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix; and double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency compared with 2015.

Each member state had the opportunity to adjust and modify the model, thus ensuring that it reflects its expectations, priorities and targets.

Utama emphasised that AEO 6 includes “comparative scenarios versus baseline, current energy planning, more implementation on renewable energy and energy efficiency targets, as well as the implementation of SDG 7.”

Key findings

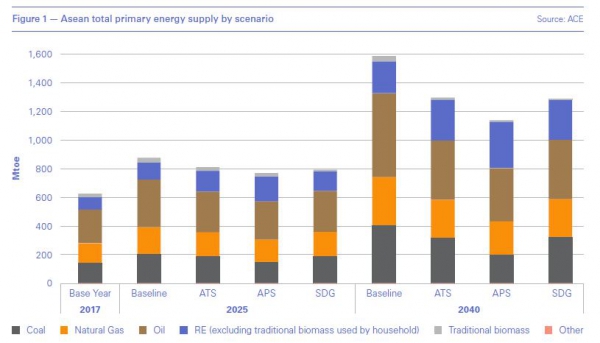

In the Baseline scenario total primary energy supply (TPES) goes up 2.5 times between 2017 and 2040, reflecting the increase in population and in living standards. But even though the increase is lower in the APS scenario, it still is about 80% over and above 2017 levels. This is why Asean countries have no option but to rely on all fuels and technologies to ensure uninterruptible energy supplies.

The key findings are summarized in Figure 1.

Clearly, even though renewable energy increases to 28.7% of TPES by 2040 under even the most ambitious APS scenario, coal, oil and natural gas still play major roles, providing over 70%. The proportion is even higher in the other scenarios. Oil continues to be the number one fuel, providing around a third of TPES during the next two decades under any scenario.

Coal remains important to the region, even up to 2040, reflecting the region’s considerable reserves and its low cost. Under the Baseline scenario coal provides 25.3% of TPES in 2040, and 16.8% under APS.

Natural gas continues to play a major role, providing about 21% of TPES throughout the reference period for all scenarios.

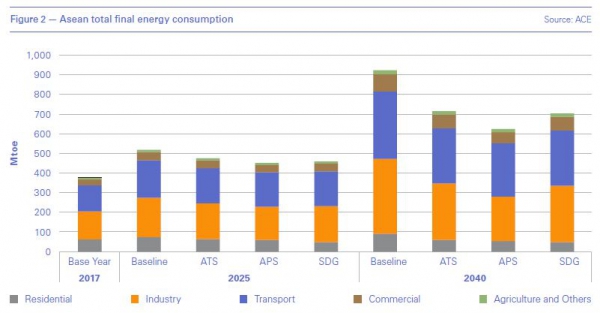

AEO 6 recommends stringent energy efficiency measures and stricter emission standards in order to slow down energy demand growth in industry.

It also says that cuts in the transport sector can be achieved by adopting stronger policies on both demand and supply for both biofuels and electric vehicles. Vehicle fuel efficiency needs to be higher, vehicle emissions need to be cut; and fuel quality standards and investment in public transit and non-motorised transport are needed to reduce the need for driving.

Another measure recommended in AEO 6 is increased electrification of transport.

The projected increase in electricity demand in the region is phenomenal. It is expected to double by 2040, providing 25.8% of total final energy consumption under the APS scenario. ACE states that responding to such growth while managing costs will be challenging, suggesting that development of the Asean Power Grid (APG) can play a crucial role in this context. The APG facilitates electricity trading through strategic interconnections, enhancing the integration of Asean power systems.

Most electricity is produced using natural gas (36%) and coal (31%). Except for hydropower, which made up 19.7% of the power mix in 2017, renewable power generation capacity in Asean remains insignificant. This can only be changed by adopting enabling measures and policies.

The role of natural gas

It is clear from Figure 1 that natural gas has and continues to have a major role to play in Asean’s energy supplies throughout the reference period. Remarkably, its contribution to Asean’s TPES appears to remain more or less unchanged, at about 21%, throughout and irrespective of scenario.

A reason for this is that more gas is used in the region’s fast-growing industrial and power generation sector despite the rise in renewables. Even under the ATS scenario, most electricity comes from coal and natural gas in the outlook.

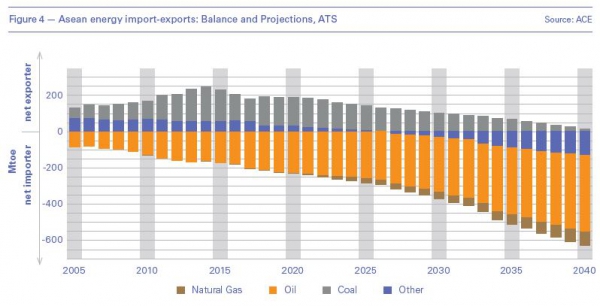

Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Myanmar and Vietnam have proven natural gas reserves, with Vietnam and Myanmar having more than 60 years’ worth of reserves at existing production rates. But despite this, Asean’s self-sufficiency in natural gas is expected to come to an end by 2026, under the ATS scenario (Figure 4).

This means that, with domestic gas production growth slowing and – in some cases – declining, Asean countries may be looking to the rest of the world for LNG. But greater reliance on imports may make gas less price-competitive.

However, there are extensive discussions taking place within Asean to promote the use of natural gas through a well-co-ordinated and connected regional gas market. Natural gas still has the potential to become the transition fuel in Asean countries.

Emissions

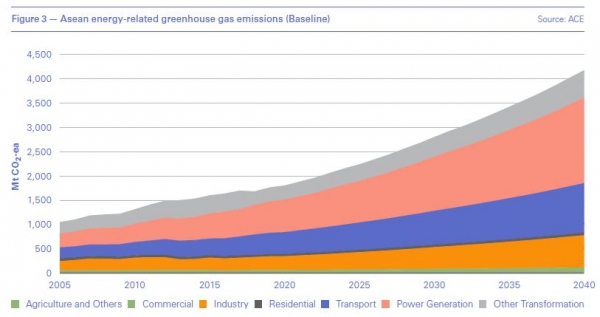

Without change, under the baseline scenario, Asean total energy-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are estimated to increase by close to 250% by 2040 in comparison to 2017 (Figure 3). The biggest contributor to this is power generation, contributing about 40%.

Analysis by ACE showed that GDP growth is by far the biggest driver of energy emissions growth in the Baseline scenario. As a result, ACE concluded that “The clear connection to rising incomes has important policy implications for Asean states…. If member states want to avoid a surge in energy-related emissions, they need to make far more ambitious efforts to reduce energy intensity and carbon intensity than they have made until now.”

As a region with many emerging economies, Asean cannot afford to adopt measures that slow down economic growth. Its members are therefore proposing stepping up national energy efficiency and renewable energy targets and adopting more ambitious GHG emission reduction targets. They aim to achieve these by changing their energy mix to rely less on fossil fuels and by adopting sector-specific measures. In AEO 6 the implications of fully implementing these national policies are modelled in the ATS scenario.

Under this the increase in emissions between 2017 and 2040 is confined to about 80%. Even though still very high – given that the world is aiming for net-zero emissions by 2050 – this would be a substantial improvement.

The increase in emissions can be slowed down further, to about 34% between 2017 and 2040, under the APS scenario. This would require solar capacity to grow by 15%/year from 2017 levels by 2040, and wind capacity, by 12%/year, mostly replacing coal-fired power.

From 2020 to 2025 alone, the ATS scenario requires solar PV capacity to go up from 32 GW to 83 GW, a 159% increase – which is quite a jump.

In addition to fuel-switching and energy efficiency measures, ACE recommends that Asean countries cut GHG emissions by deploying new, more efficient, technologies such as clean coal technologies, high-efficiency low-emissions coal power, carbon capture utilisation and storage and more electric vehicles.

Energy security

A key factor for the Asean region, much the same as for most Asia-Pacific region countries – especially China – is energy security and security of energy supplies. In fact, the theme of APAEC Phase II is “Enhancing Energy Connectivity and Market Integration in Asean to Achieve Energy Security, Accessibility, Affordability and Sustainability for All.”

The import dependency of ASEAN countries corresponding to the ATS scenario is shown in Figure 4.

It is evident that reliance on fossil fuels is growing and with it import dependency goes up with time, especially for oil. From being net exporters, by 2026 Asean countries are expected to become net gas importers. But they will remain net exporters of coal until at least 2040.

Nevertheless, according to ACE “the region imports 40% of its primary energy supply, and there is concern about local resources increasingly falling short, which continues to put pressure on regional energy security.”

Asean states recognise that none of them can fully address their energy issues on their own and that regional co-operation is crucial. Energy connectivity has been identified as a prominent issue, with the first multilateral power trade in the region, successfully initiated under the Asean Power Grid (APG) programme between Laos, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore. Inter-connectivity can also be instrumental in promoting the development and use of renewable energy in the region.

The commitment to collaboration has been cemented through APAEC, a series of guiding policy documents, in two five-year phases covering the period 2016 to 2025.

Lower fossil fuel imports through increased energy efficiency and faster transition to renewable energy sources, mainly in the transport and power sectors, have the potential to improve Asean’s energy security.

Asean has also been co-operating with China, Japan and South Korea to enhance energy security in view of the surging energy demand the extended region is experiencing to support economic growth. This includes information sharing, energy storage, oil stockpiling, development of integrated energy security policy and transformation of the energy mix towards cleaner technology.

Energy security concerns and lower costs may become the key drivers that away Asean and Asia-Pacific governments into faster implementation of renewable energy.

Challenges

Asean countries are being criticised for being too slow in the adoption of renewables and transition to clean energy, despite the fact that the region is endowed with ample wind and solar resources.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has gone as far as to warn in its Southeast Asia Energy Outlook that current power development proposals will see the region remain heavily dependent on fossil fuels for decades to come.

This is reflected in the fact that even under the most ambitious scenario, APS, renewable energy provides only 28.7% of TPES by 2040, despite the fact that Asean aims to achieve a 23% contribution by 2025.

But there are doubts that it will achieve even that. The IEA warns that without a stronger policy push, the share of renewables in the energy mix is projected to stay flat at around 15% through to 2025.

Even more worrying, the IEA estimates that current energy plans could see the region more than double its coal-fired power capacity by 2040. Even under the APS scenario, Asean’s coal demand is expected to increase by over 40% between 2017 and 2040.

However, there are hopes for change, led by Vietnam that appears to have embarked on an ambitious and rapid increase in the use of solar and wind power, moving away from coal. Other Asean countries appear to be following Vietnam’s lead. The IEA says that declining clean power costs, and concerns about emissions and air pollution, have begun to alter the balance of future additions to southeast Asia’s energy mix, boosting the shares of renewables at the expense of coal.

But as the IEA has identified, rising incomes, industrialisation and urbanisation are the powerful forces driving the expansion of southeast Asia’s energy system. The member states “recognise that strong renewable energy and energy efficiency measures are pivotal solutions to reduce dependency on fossil fuels, strengthen energy security and lower GHG emissions,” but the priority is economic growth.

AEO 6 addresses key aspects of energy trends, policies, socio-economic development, and recommends the member states to put in place stronger policies and increase their efforts, particularly for renewable energy and energy efficiency development beyond existing national targets. It remains to be seen whether, post-Covid-19, Asean governments will seize the opportunity to make serious energy policy reforms promoting cleaner energy – but there are already some positive signs.