South Korean LNG: feast or famine? [LNG Condensed]

NOW AVAILABLE:

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

_f400x512_1569931982.jpg)

Volume 1, Issue 9 - September 2019

In this Issue:

Editorial: EIA outlook highlights growing energy policy gap

Shipping futures: is LNG the fuel of choice?

South Korean LNG: feast or famine?

Australia top dog - for now at least

Country Focus: Brazil locking in LNG demand

Project Spotlight: Calcasieu Pass

Technology: China eyes the LNGC Market

and more!

LNG Condensed brings you independent analysis of the LNG world's rapidly evolving markets.

Covering the length of the LNG value chain and the breadth of this global industry, it will inform, provoke and enrich your decision making. Published monthly, LNG Condensed provides original content on industry developments by the leading editorial team from Natural Gas World.

LNG Condensed is your magazine for the fuel of the future.

Sign up to NGW Basic FREE or to NGW Premium now to receive LNG Condensed monthly (you will find every issue of LNG Condensed in your subscriber dashboard)

South Korean LNG imports reached a record 44.5mn mt in 2018, but demand is currently falling. Subdued economic growth, stringent energy conservation measures and competition from other fuels are expected to constrain future growth, while in the longer term LNG could face competition from imported piped gas and electricity. But that doesn’t mean the future will be all gloom and doom.

For now, though, the 17% year-on-year surge in LNG imports in 2018 seems a distant memory following a dismal run of figures in 2019. Customs data shows South Korea imported 22.937mn mt of LNG during the seven months from January to July, down almost 10% from the 25.423mn mt imported in the same period of 2018.

This partly reflects the deteriorating global economic environment. The US-China trade war is a particular headache for South Korea, given the US is one of its key political allies while China is one of its main trading partners. This has been compounded by the country’s highly-politicised economic dispute with Japan, one of its other main trading partners.

As a result, the Bank of Korea cut its economic growth forecast for 2019 from 2.5% to 2.2% in July. Many analysts are more pessimistic still. In July, the ratings agency Standard & Poor’s cut its 2019 forecast from 2.4% to 2.0%.

The slowdown in economic growth has fed through into energy demand. Total final energy consumption fell from 102.23mn tons of oil equivalent (toe) in January-May 2018 to 100.81mn toe in the same period of 2019, according to the Korea Energy Statistical Information System (Kesis). Kesis data shows LNG demand fell much more sharply between the two periods – down almost 10% from 19.53mn mt to 18.01mn mt.

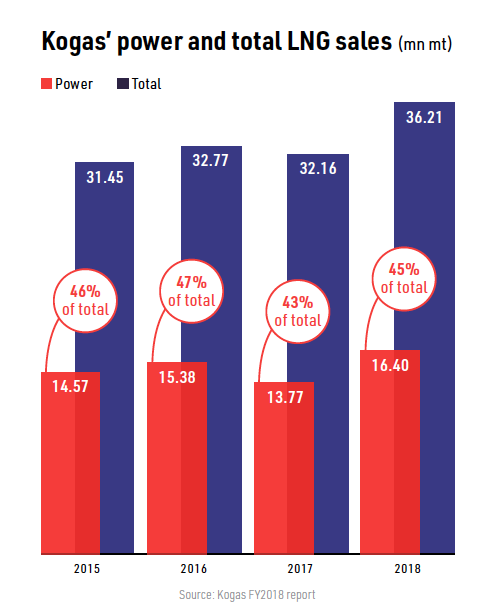

The trend has continued. In June, the state-owned Korea Gas’s year-on-year LNG sales -- which had already fallen for seven months in a row -- slumped 14% to 1.9mn mt. The fall meant Kogas’ sales for first-half 2019 fell more than 9% year on year to about 17.9mn mt.

Power sector uncertainty

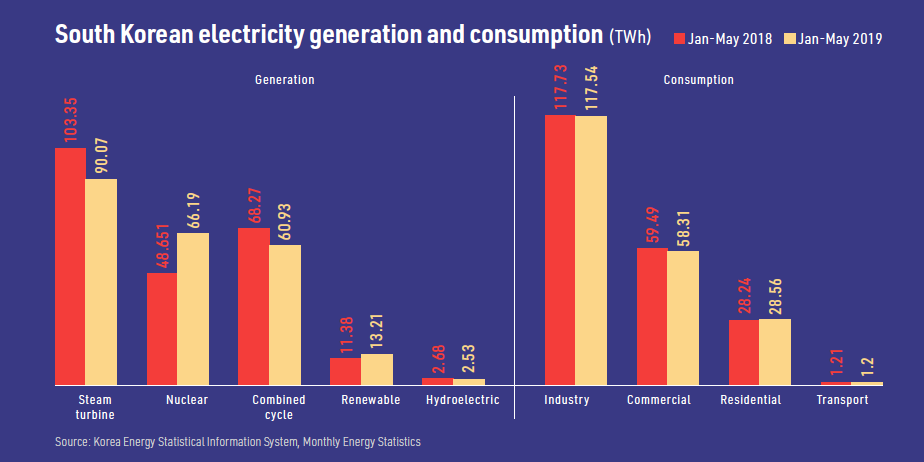

Much of the fall in sales occurred in the power sector, which accounts for almost half South Korean LNG use. Electricity generation fell from 234.6 TWh in January-May 2018 to 233.2 TWh in the same period of 2019, according to Kesis.

However, there was a much greater fall in gas-fired generation and thus LNG burn. Kogas’ sales to generators fell almost 25% year on year to 0.93mn mt in June, whereas its city gas sales were down a modest 0.8% to 0.98mn mt.

The slump in LNG burn reflects not only the fall in electricity demand, but also increased output from nuclear and renewable generators. Kesis data shows nuclear output for January-May 2019 jumped 36% year on year to 66.19 TWh as reactors closed for maintenance and safety checks resumed operation.

Nuclear output is set to rise further as new units enter service. In late August, the 1,400-MW Shin Kori-4 reactor entered commercial operation. This took the country’s reactor fleet to 24 with 23.23 GW of capacity, according to the World Nuclear Association. Five of these reactors with 4.3 GW of capacity are scheduled to close by 2026, but four new reactors with 5.6 GW of capacity are due to enter operation by 2024. This means President Moon Jae-in’s 2017 commitment to phase out nuclear can only start in earnest in the late 2020s.

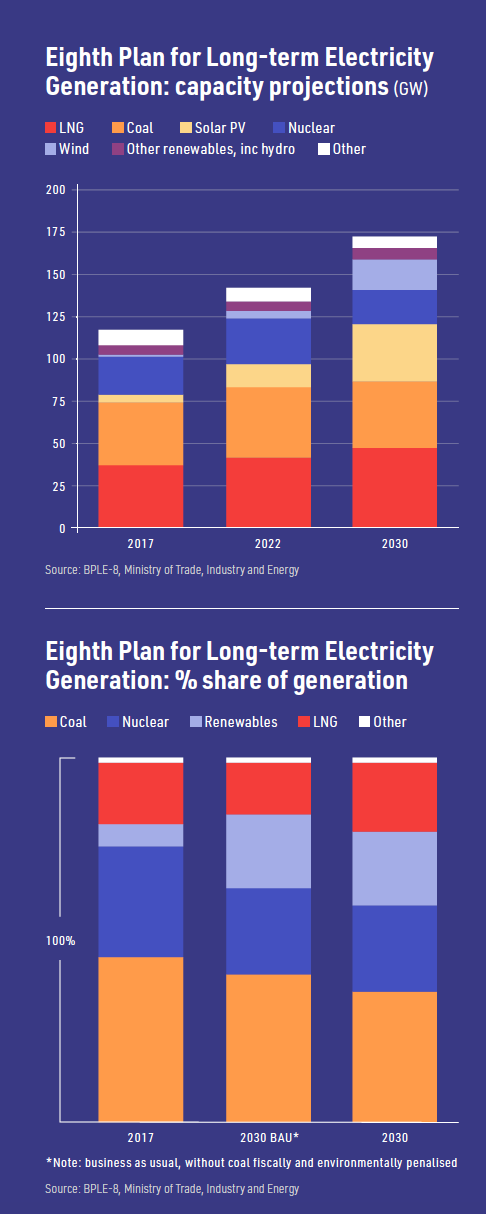

Renewable generation grew less strongly and from a lower base, but the 16% year-on-year jump to 13.21 TWh in January-May 2019 was still substantial. Moreover, renewable output is expected to balloon. In the government’s latest long-term electricity plan, issued in 2017, renewables account for 20% of generation in 2030, compared with 6% in 2017. The increase assumes the installation of 33.5 GW of solar and 17.7 GW of wind capacity by 2030.

In April, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (Motie) went further. It told a public hearing the renewable share was targeted at 30-35% in 2040, implying renewable capacity of 103-129 GW.

Government priorities

Coal-fired generation is expected to bear the brunt of increased renewable generation, with Motie director Park Jae-young telling the public hearing that gas use would grow. However, greater renewable generation in combination with increased nuclear output and other factors could hit gas-fired output in the near to medium term.

The other factors include the low growth in electricity demand projected as a result of additional energy-saving measures. In early 2019 the government said that more conservation could see 14% shaved off ‘business as usual’ demand in 2030.

Moreover, gas-fired generators must still compete with coal-fired generation, with seven new plants due to be commissioned by 2022 and coal-fired capacity only set to fall from 2030.

While coal is being penalised by progressively-rising import taxes, there is no certainty taxation, carbon pricing or other measures will be sufficient to force the widespread replacement of coal by gas any time soon.

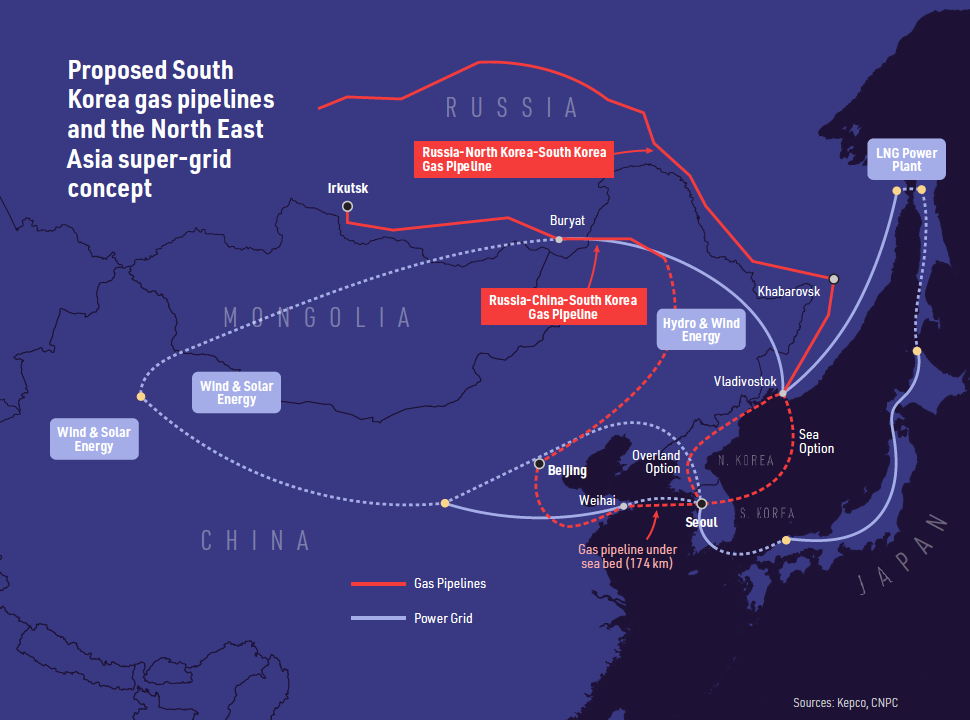

On top of all this, LNG’s role in South Korean gas supply could be challenged by piped gas imports, while imported electricity may also compete with gas-fired generation if the proposed Northeast Asian Super Grid is implemented.

It is thus unsurprising that South Korea’s 2018 Natural Gas Plan forecast demand in 2031 of only 40.49mn mt – some 4mn mt lower than in 2018.

Piped gas import plans

The currently-favoured pipeline project would deliver gas overland from Siberia and the Russian Far East through North Korea. A 2010 assessment by South Korea and Russia envisaged imports to South Korea reaching 7.5mn mt/year. A 2015 study suggested the line would run 1,200-1,500 km in North Korea, depending on whether it delivered gas to Pyongyang and Kaesong.

This would affect the project cost, broadly estimated at $2.5 billion by Russia’s Gazprom. However, if the longer route is adopted North Korea could get its transhipment fees in the form of gas. The annual fees have been estimated by Kogas at $158 million.

The project was boosted in 2017 with the election of Moon Jae-in, who favours closer ties to Pyongyang. It has also benefited from US President Donald Trump’s diplomatic initiatives with North Korea. In June 2018 a joint feasibility study by Kogas and Gazprom into the project was agreed by Moon Jae-in and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

But for all its high-level backing the project remains problematic, with sanctions against North Korea one of the key constraints. North Korea’s political volatility is also a concern. And in June 2019 the Korea Energy Economics Institute noted the project was hamstrung by political rather than economic reasons, not least because the three countries have very different political agendas.

Less attention has been paid recently to two proposed undersea gas pipelines from Russia that would avoid North Korea. One would run through China and enter South Korea from the west. The other would run from Vladivostok to the east coast of South Korea. The options appear to be being downplayed because of Seoul’s desire for rapprochement with North Korea, rather than cost or technical reasons.

Importing power

More interest has been shown in the Northeast Asian Super Grid, which would form part of the wider Asian Super Grid and integrate the electricity markets of China, Mongolia, Russia, Japan, and the two Koreas. The project is centred on the supply of renewable energy from, for instance, Mongolian wind and solar farms to energy-poor regions such as South Korea.

While a trans-Asian grid has been dreamed about for decades, the project gained traction in 2016 when it was promoted by Japan’s Softbank. One of the other main promoters is the South Korean power company Kepco. The cost was estimated by Kepco in late 2018 at Won 7.2-8.6 trillion ($6-7.2 billion), depending on which Japan-Korea link is chosen.

The China-South Korea section is one of the most advanced components of the project, although the initial proposal for an undersea link has shifted to one running through North Korea. In May 2018 a meeting of Chinese and South Korean officials agreed to implement an initial 2-GW project from 2022.

However, the project must still overcome serious problems, not least the issue of North Korean sanctions. The overall project has also been affected by the dispute between South Korea and Japan.

All still to play for

While South Korean LNG prospects may appear bleak, appearances can be deceptive. The feasibility of building large amounts of renewable plant is uncertain; the current support for nuclear could evaporate as a result of even a minor incident at home or abroad; while fiscal measures and popular opposition are eroding coal’s position.

Meanwhile, energy demand is shifting from industrial consumption to more peaky residential use, which will benefit LNG. If circumstances conspire in its favour, LNG demand in 2030 could exceed 50mn mt just as easily as it could dip below 40 million mt if they conspire against it.

The picture beyond 2030 is even less clear. Nuclear and coal-fired output is slated to fall, but renewables together with piped gas and electricity imports could exert significant downward pressure on LNG use.

Building 129 GW of renewable plant will be hard, while neither import option is likely to be single-mindedly embraced by Seoul at the expense of LNG. South Korea’s heavy dependence on imported energy means it is unlikely to sacrifice the diversity of sourcing and delivery options offered by LNG in favour of less flexible and potentially more-risky options.