Sino-Australian dispute threatens LNG trade [Gas in Transition]

China is Australia’s biggest trading partner and the two most valuable Australian exports to China, LNG and iron ore, have thus far been relatively unaffected by the deterioration in political relations. However, there are fears that continued enmity will eventually damage trade in LNG.

The dispute between the two countries began in 2017 when Canberra announced that China had attempted to interfere in Australian politics. This prompted Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull to say that Australia would “stand up” to Chinese bullying, just three years after Chinese premier Xi Jinping had been invited to speak to both Australian houses of parliament.

The Australian government also accused Beijing of intimidating Chinese Australians, while the latter have come under pressure from Canberra itself to prove their loyalty to Australia.

Since then, a series of tit-for-tat claims and economic measures have seen relations nosedive. Planned Chinese investment in Australia, including by Huawei in building a 5G network, have been blocked by the Australian government.

The heat turned up significantly last year when the Australian government requested an independent investigation into the origins of Covid-19. Beijing responded by imposing sanctions on Australian imports and then publishing a list of 14 grievances in 2020.

This year, China suspended the China-Australia Strategic Economic Dialogue, which is designed to iron out economic difficulties between the two.

China has adopted a robust foreign policy under Xi and has reacted by seeking to restrict many Australian imports, ranging from coal and copper to wine and barley. Tariffs on some products were increased, some imports were virtually blocked entirely and Chinese companies in several sectors appear to have been instructed to avoid Australian imports.

China has adopted a robust foreign policy under Xi and has reacted by seeking to restrict many Australian imports, ranging from coal and copper to wine and barley. Tariffs on some products were increased, some imports were virtually blocked entirely and Chinese companies in several sectors appear to have been instructed to avoid Australian imports.

Coal trade between the two collapsed dramatically, but the move appears to have had a detrimental impact on China itself, which has struggled to secure sufficient thermal and coking coal from other producers. Lloyds List reports that coal shortages in China have prompted Chinese port authorities to allow the unloading of some Australian coal cargoes in October.

Aukus

The Australian government appears to have calculated that it needs allies in maintaining a harder line on China. Most notably, it signed the Aukus regional security agreement with the US and UK in September, under which the US will provide the technology for Australia to build nuclear-powered submarines and long-range missiles, joining an elite club of just six nations who already have them.

The UK is the only other country to have benefitted from US nuclear submarine technology. Never before has the Australian military had the ability to strike opponents at long range.

For many years, Australia tried to balance its relations with China and the US, but it now seems to have firmly moved into the US camp, diluting its long standing policy of pivoting towards Asia. The leaders of the US, UK and Australia said that the pact was designed to address regional security concerns that had “grown significantly”, in clear reference to China.

Beijing condemned the security pact as “extremely irresponsible” and said it risked “severely damaging regional peace”, which only underlined its significance.

One of Canberra’s biggest fears is China’s growing military power and its attempts to assert its control over the South China Sea, which is subject to many conflicting sovereignty claims with other countries in the region. The governments of the biggest trading nations in Southeast Asia are reported to be publicly annoyed, but privately pleased about Aukus: annoyed that they were not consulted, but pleased that the US in particular has restated its commitment to regional security.

Impact on LNG

The impact on the commodities that China needs most but finds difficult to source elsewhere, such as iron ore and LNG, has been less profound. Iron ore exports from Australia to China stood up at $53bn in the first half of this year, while trade in LNG has thus far been little affected.

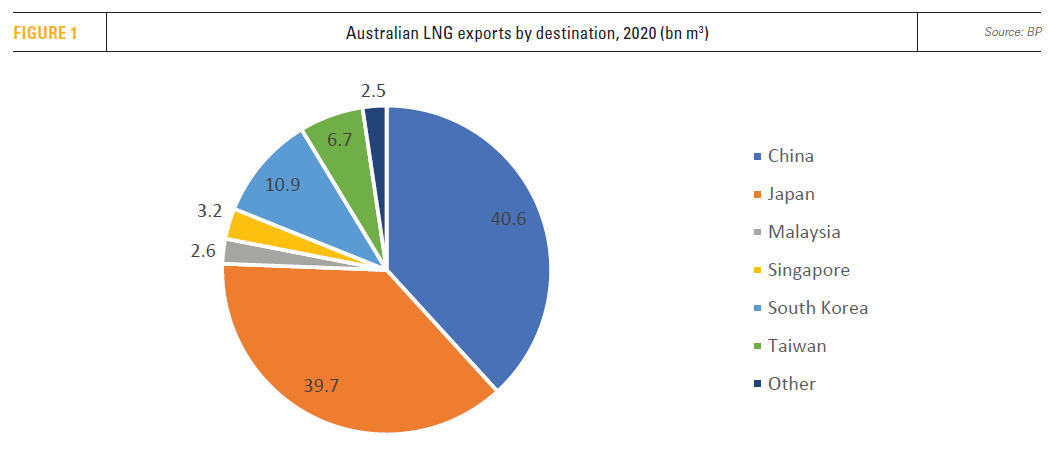

Indeed, China has now overtaken Japan as the biggest market for Australian LNG (Figure 1). A total of 29.8mn mt was shipped in the fiscal year to the end of June 2021, representing 39% of Australian LNG exports, up from 37% in the previous year.

Japan imported 28mn mt of Australian LNG over the same period, but both countries were a long way ahead of the next biggest customer, South Korea, with 8mn mt.

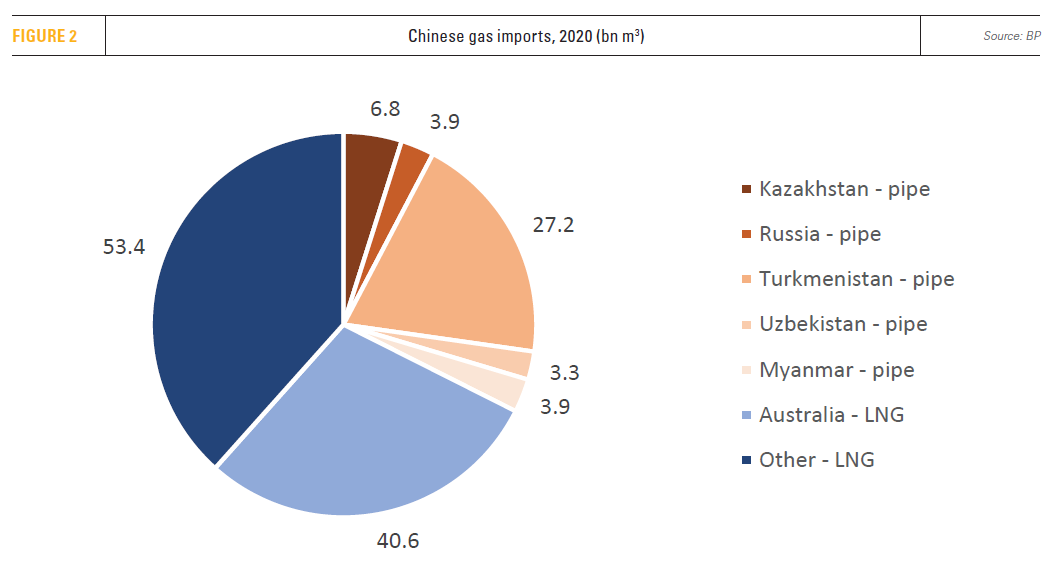

This makes Australia highly dependent on the Chinese market, yet Beijing is just as reliant on Australian gas (Figure 2). China imported 41% of its LNG from Australia in the year to the end of June 2021.

High spot prices this summer and ahead of winter indicate a lack of spare LNG supply and China would be hard pressed to source such significant volumes of LNG from elsewhere. The most likely source would be the US, the other prime mover in the Aukus agreement.

Sino-Australian interdependence

Australian LNG exports to China have increased rapidly as a result of two interlinked trends: China’s huge and growing thirst for LNG as it promotes coal-to-gas switching and tries to battle both greenhouse gas emissions and local air pollution, and Australia’s desire to monetise its offshore gas and coal bed methane (CBM) reserves.

These two influences remain intact, so there is huge pressure for the geographically convenient trade to continue. The Australian share of the Chinese market looks set to fall as Chinese demand continues to rise and no new Australian LNG capacity is scheduled to come on stream. But, politics aside, Australia should remain a major LNG supplier to China.

There have been reports that at least two smaller Chinese importers were instructed not to buy Australian LNG earlier this year, but it does not appear that the country’s biggest LNG customers: China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. (Sinopec), PetroChina and the China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC), have been affected.

While still significant, it is likely that only spot cargoes would be hit, as the big three buyers would struggle to extricate themselves from their long-term supply contracts. Sinopec and CNOOC also both have equity investments in Australian LNG projects.

The big three Chinese importers have actually been prepared to boost their imports of Australian LNG, with very tight gas supplies in much of the world and spot LNG in Asia trading around $20/mn Btu, a record level for this time of year. Australian consultants EnergyQuest reported that the North West Shelf, Queensland Curtis and Australia Pacific LNG projects have all been supplying China with volumes above their long-term contracted agreements, while even those Australian plants without long-term deals were supplying spot cargoes to Chinese customers.

Beijing’s decision not to target Australian LNG reflects a big increase in domestic gas demand on the back of the COVID-19 recovery, markedly higher coal prices and lower hydropower production in China, with Chinese gas-fired power generation 14% higher in the first four months of 2021 in comparison with the same period last year.

Its approach may change if and when the LNG market slackens, but, even then, would likely be limited to spot market purchases.

Inward investment

Chinese investment in Australia fell by 61% in 2020 in comparison with 2019. But for the LNG sector, Australia would have been in a far more vulnerable position had it been seeking new long-term supply contracts with Chinese customers. This now looks increasingly unlikely, particularly with regard to CBM. Three LNG projects have already been developed in Queensland using CBM: the 9mn mt/year Australia Pacific project, 8.5mn mt/year at Queensland Curtis and 7.8mn mt/year at Gladstone, but further CBM projects look set to focus on hydrogen rather than LNG production.

Australia exported 77.2mn mt of LNG in the fiscal year to the end of June 2021, a fall of 2.3mn mt on the previous year, partly because of gas supply problems on the country’s first LNG project, North West Shelf, and technical issues on several other projects. This is someway short of total Australian nameplate capacity of 88mn mt/year, but any further output is likely to be traded on the spot market and, given current demand, is likely to find a home, with or without Chinese interest.

Conflict duration

The big question is how long this conflict is likely to endure. China and Australia are obvious trading partners, but that economic interdependence has not been sufficient to calm tensions over the past four years. At each stage, the dispute has been fuelled by a policy decision by one side or the other, most recently by Aukus.

A change of heart – or government – in Canberra could solve the problem, but Beijing’s tactics have only served to drive up indignation among Australian politicians of all hues, so any attempt at rapprochement looks some way off. For its part, China’s political sentiment famously takes a long time to change, so any new policy is likely to be a change in degree rather than direction.

A change of heart – or government – in Canberra could solve the problem, but Beijing’s tactics have only served to drive up indignation among Australian politicians of all hues, so any attempt at rapprochement looks some way off. For its part, China’s political sentiment famously takes a long time to change, so any new policy is likely to be a change in degree rather than direction.

At present, the most likely outcome is for the conflict to rage on for the foreseeable future.

However, China seems unable to satisfy its demand for LNG and iron ore with other suppliers, so those two commodities could remain relatively untouched for now. Two things could change that: a further, significant escalation of the conflict, perhaps driven by military rivalry between China and Australia, the UK and US, and their allies within the region; or increased supply options.

Given how long it takes to develop LNG projects, the latter would be a fairly lengthy process, but a warm northern hemisphere winter could take the heat out of the LNG market and provide Chinese buyers with greater supply flexibility. Nonetheless, Sino-Australian tensions could well benefit developments in other countries, for example Qatar, which is certain to be looking for more, firm off-takers for its major North Field expansion project.