Shell unveils LNG outlook amid heightened uncertainty [Gas in Transition]

The LNG market rebounded in 2021 despite supply constraints, with global trade increasing by 6% to 380mn metric tons, Shell notes in its LNG Outlook 2022 released on February 21. By 2040 this is expected to reach 720mn mt, driven by growth in demand in Asia, as LNG replaces coal as a result of pledges to achieve net-zero by 2050-70.

Shell’s key conclusions are that:

- As a reliable, available and lower-emissions energy source, gas has an important role in supporting energy transition, both as a partner to renewables for grid stability and as an immediate option to lower emissions in hard-to-electrify sectors.

- LNG has a key role to play particularly in Asia, replacing declining domestic gas production, enabling coal-to-gas switching and supporting economic growth

- The volatility in energy prices in 2021 shows how quickly the energy market can destabilise without sufficient reliable supply.

- 2021 saw increased momentum in efforts to decarbonise the LNG value chain, a crucial factor for its long-term role in the energy mix.

- China overtook Japan as the world’s largest LNG importer while US led growth in LNG exports and is expected to become the world’s top exporter in 2022.

In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, energy markets have become destabilised and distorted like never before. The oil and gas in industry is entering uncharted territory, with global natural gas markets in particular undergoing rapid change. Europe is accelerating efforts to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, including natural gas, and expand renewables. Russia is also fast-tracking its pivot to China, as witnessed by the growing number of gas pipeline and LNG exports deals that have been reached between the two countries over the last few years.

In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, energy markets have become destabilised and distorted like never before. The oil and gas in industry is entering uncharted territory, with global natural gas markets in particular undergoing rapid change. Europe is accelerating efforts to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, including natural gas, and expand renewables. Russia is also fast-tracking its pivot to China, as witnessed by the growing number of gas pipeline and LNG exports deals that have been reached between the two countries over the last few years.

In the short-term, though, energy security concerns, geopolitics vis-a-vis Russia, the economic recovery from COVID-19 and growing inflation have magnified the energy crisis, trumping climate issues. Worried about the security of its gas supplies from Russia, Europe has prioritised securing alternative supplies, especially LNG. But it has to compete with Asian markets which, according to Shell’s LNG Outlook 2022, will drive future LNG demand growth.

While all this is happening, oil and gas prices are sky-rocketing and, with rising demand and increasing supply constraints, they are likely to remain high for the best part of this decade. Not only is this encouraging a return to coal and nuclear energy, but it is also accelerating the uptake of renewable energy, particularly in Europe, at the expense of oil and gas as we approach 2030 and beyond.

Global LNG demand will grow

Shell forecasts that an LNG supply-demand gap will emerge in the mid-2020s, especially in Asia. But given Europe’s determination to diversify its own gas supplies in its drive to become independent of Russian gas by 2030, this gap is set to appear earlier. Europe is scouring the world for more LNG imports, exacerbating its competition with Asia for supplies and resulting in higher and more volatile prices for longer.

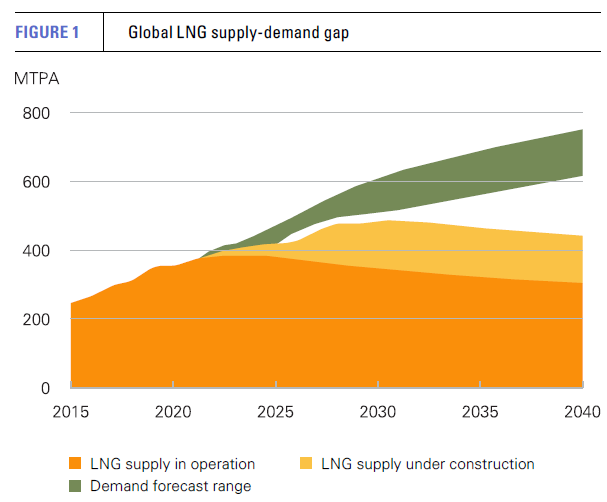

LNG export growth in 2021 was led by the US, which Shell said was tipped to become the world’s largest LNG exporter in 2022. Global LNG demand is expected to exceed 720mn mt by 2040 (Figure 1), from about 380mn mt/yr in 2021 – an increase close to 90%. According to Shell, most of this extra supply will be destined for Asia, where Shell forecasts future LNG demand will carry on growing throughout the outlook period.

The outlook states that global LNG supply is expected to be tight in 2022, with the shortfall between supply and demand increasing by 2025 – this will be exacerbated by Europe’s turn away from Russian gas to LNG, at least in the short-term. Shell forecasts this gap to increase to 200mn mt/yr by 2040.

This is what has led Shell to call for an increase in investment in new LNG supply projects to meet this rising demand.

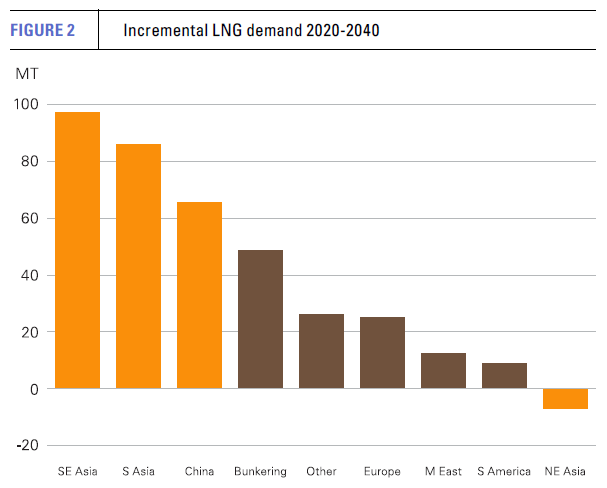

China in particular will drive growth between 2020 and 2040, with Shell estimating it will require an addition 65mn mt/yr by the end of the period (Figure 2), as its economy grows and as – beyond 2030 - the country switches from coal to cleaner fuels to meet its pledge to achieve net-zero by 2060.

According to Shell, in 2021 Chinese LNG buyers signed long-term contracts for more than 20 mn mt/yr. But the question is whether this will continue at the same pace in light of the shake-up in energy markets as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its pivot to China. It remains to be seen.

Shell notes that “as countries develop lower-carbon energy systems and pursue net-zero emissions goals, focusing on cleaner forms of gas and decarbonisation measures will help LNG to remain a reliable and flexible energy source for decades to come.” Certainly that remains true, but for how long? As investment in renewables, hydrogen, CCUS and other clean energy technology is vastly increased and accelerated in response to the global energy crisis, the day of reckoning for fossil fuels will get closer.

Decarbonisation of LNG

Shell’s outlook states that “successful efforts to reduce emissions from natural gas and develop cleaner pathways will bolster LNG’s role. During 2021, momentum picked up for decarbonising the LNG value chain with several announcements around investments to address emissions.”

This is still important if LNG is to fulfil its role as backup to intermittent renewable power supply during energy transition and in coal-to-gas switching. As the outlook states, “as a reliable, available and lower-emissions energy source, gas has an important role in supporting this transition, both as a partner to renewables for grid stability and an immediate option to lower emissions in hard-to-electrify sectors.”

Switching just 20% of coal-fired power in Asia to gas can potentially save 680 mt/yr of CO2. This is equivalent to all annual emissions from Germany.

The EU’s conundrum

The EU’s plan to replace Russian gas will likely face many difficult-to-overcome obstacles. It is more easily said than done. Analysts from Bruegel conclude that “if Russian gas stops flowing, measures to replace supply won’t be enough. The EU will need to curb demand, implying difficult and costly decisions.” Or it will continue relying on Russian gas, but in reduced quantities.

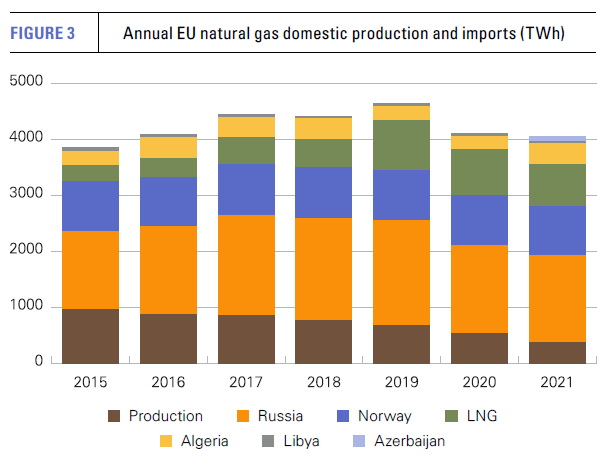

And it will not be just Russian gas that will have to be replaced in the period to 2030. It is also declining domestic production (Figure 3). This has been in constant decline for years, going from 24% in 2015 down to just 9% in 2021. And it is expected to carry on declining.

What Figure 3 shows is that by 2030, the EU may need to replace almost 50% of its gas consumption – a tall order. Even if it can secure more LNG, that will not be enough. And with intermittency still a problem, renewables will not be enough either. Hence Bruegel’s conclusion.

Challenges

In the topsy-turvy world we have entered following the invasion of Ukraine, established order in energy markets has now been upended for good. It is no longer a case of a gradual energy transition. Fast-evolving geopolitics have made security of supplies the priority. A bi-polar world is emerging with the US and the EU on one side, and China and Russia on the other, with the rest of the world caught in between. This also applies to energy.

With everything interconnected, decoupling is difficult and in cases painful. Shunning Russian oil and gas may hurt Russia, but it is also hurting the countries that import those supplies as well as the global economy. Prices of everything are increasing, from energy, to food, to goods, transport, and so on, and with them inflation, which has reached highs not seen since 2008.

All this comes at a high cost to consumers and taxpayers, particularly in Europe and partly in the US. How they react will define how energy policies develop. One thing for sure is that the EU’s push to end reliance on Russian energy is effectively fast-forwarding its energy transition strategy.

The paradox is that many of the sanctions are designed to hurt Russia’s economy by starving it from export revenues, and in particular from oil and gas. But even if such efforts manage to curtail Russian exports, with oil and gas prices sky-rocketing since the invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s revenues would hardly see a change – unless of course its exports are completely stopped, which is not possible.

The paradox is that many of the sanctions are designed to hurt Russia’s economy by starving it from export revenues, and in particular from oil and gas. But even if such efforts manage to curtail Russian exports, with oil and gas prices sky-rocketing since the invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s revenues would hardly see a change – unless of course its exports are completely stopped, which is not possible.

Switching from Russian gas to LNG in Europe is likely to increase global LNG demand by as much as 10% this year. But, at least in the near-term, global supply capacity cannot be increased in response to this. The expected 25 mn mt growth in LNG supply this year is already largely contracted. In addition, about 65% of global LNG supply is already committed to long-term contracts. Securing this additional LNG will prove to be a major challenge for Europe. High prices are likely to become even higher, encouraging a return to coal. Achieving climate change targets may no longer be a priority.

Europe is looking to the US to provide it with LNG to become independent of Russian gas. But, with renewables and hydrogen being accelerated to fill the gap, this is a short-term requirement – at least that is what Europe believes, even though reality may be different. Nevertheless, that is the signal the EU is passing to the US LNG producers and exporters. Given the current tightness of US LNG production, this will require new projects. But it takes five years for such projects to go from final investment decision to the start of exports. So, these producers will be forced to look to Asia for their longer-term exports to justify commercial viability.

What this ignores is the realignment in global energy markets in the aftermath of the Ukraine conflict. Already Russia and China have signed pipeline deals to deliver close to 100bn m3/yr of Russian gas to China by 2030 and more as LNG. Chinese companies are also participating in Russian gas and LNG projects, with their shareholdings likely to increase following the departure of Western majors.

Even though Chinese gas demand is growing, the additional Russian gas could fill the gap between demand and supply, limiting China’s need to import more LNG.

Ultimately, this additional Russian gas – some of it diverted from gas fields supplying Europe to China – could replace the entire 90bn m3/yr, estimated by Shell to be the incremental LNG demand in China between 2020 and 2040.

Another challenge will be the impact of high gas prices caused by the upheaval in global energy markets as a result of the Ukraine conflict. European futures markets show the price of gas remaining above $30/mn btu into 2024 and possibly beyond.

This is hastening the transition to renewables (wind, solar, biogas, biomethane) and hydrogen, but also encouraging a return to cheaper coal – despite the high EU carbon permit prices – and nuclear energy. In fact, during the ninth week of this year, Europe burned 51% more coal than it did in the same period a year earlier. As long as natural gas/LNG prices remain high, European utilities will continue giving preference to coal at the expense of natural gas/LNG.

Responding to heightened energy security concerns, China is doing something similar. Taking their cue from president Xi Jinping, who said “China could not simply slam the brakes on coal”, delegates at the mid-March annual parliamentary gathering confirmed that the country “will make full use of coal as a vital part of its energy strategy,” at least this decade. In addition, Shell has not yet been able to finalise newLNG shipments to China this year because of the high prices. As a result, China’s LNG imports are no longer forecast to rise this year. Will this continue beyond 2022? – quite possible.

India is also shunning expensive LNG imports. It seems that coal is indeed king.

Even though the return to coal may be reversed by 2030, increased renewables, hydrogen and nuclear power will permanently displace a substantial part of the energy market that, otherwise, gas and LNG might have expected to fill in a more orderly transition.

The concern is that all these developments are setting back the fight to contain climate change and global warming. In effect this is now delayed – the priority is energy security. Indicative of this is that IPCC’s new report on climate change has gone largely unnoticed.

The message from the EU is that it needs more natural gas from sources other than Russia now, but that it intends to reduce natural gas dependence by 30% by 2030 and to zero by 2050. EU and US goals remain to accelerate energy transition and reduce dependence on fossil-fuels as fast as possible. They and climate change activists are concerned that investments in new fossil fuel projects will lock-in more long-term use.

On that basis and with that message, the question is why any company would invest in long-term natural gas – or oil – projects when they do not know what the future holds, beyond a few years from now. This is a confused message that discourages investment. Should the transition to renewables and hydrogen take longer than hoped for – which looks likely – the EU will find itself exposed to energy quandaries again.

What is needed is a reality check. With renewable intermittency still a serious problem and green hydrogen technology still expensive, the world will need natural gas for a few decades more. This must be recognised and accepted by Europe and the US, with appropriate policy signals to unlock investment in new oil and gas projects – backed by CCUS – ensuring longer-term security and affordability of supplies, beyond just the next few years.