Scottish CCS project misses out on govt funding [Gas in Transition]

The UK has taken a major step forward in efforts to decarbonise its largest industrial clusters, selecting in late October two carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS) projects in northern England for state funding. But the government has faced criticism for overlooking a third project in Scotland, despite its advanced stage of planning. The project’s omission will throw a spanner in the works for a number of Scottish companies with net-zero ambitions, including those that handle and process North Sea oil and gas.

The administration of UK prime minister Boris Johnson wants to have at least two CCUS projects up and running by the mid-2020s, and at least four by the end of the decade, with the aim of capturing up to 30mn metric tons of CO2 annually for storage offshore by 2030. It launched a sequencing process this year to decide which clusters should be decarbonised first, and announced on October 19 that it had selected the UK East Coast Cluster and HyNet North West initiatives. These projects will receive some £1bn ($1.4bn) of funds from the government’s CCS Infrastructure Fund.

The East Coast Cluster will deploy CCUS across the Humber and Teesside regions, comprising three sub-projects known as Zero Carbon Humber, Net Zero Teesside and Northern Endurance Partnership. Alone it is expected to prevent 50% of CO2 emissions from UK industry from escaping into the atmosphere. BP, Italy’s Eni, Norway’s Equinor, Shell and France’s TotalEnergies are leading the development of its transport and storage infrastructure.

HyNet North West will consist of CCUS infrastructure and low-carbon hydrogen production, helping to decarbonise industry in northwest England and north Wales. It will handle 10mn mt/yr of CO2 by 2030, and provide almost half of the hydrogen supply envisaged in the UK’s net zero strategy.

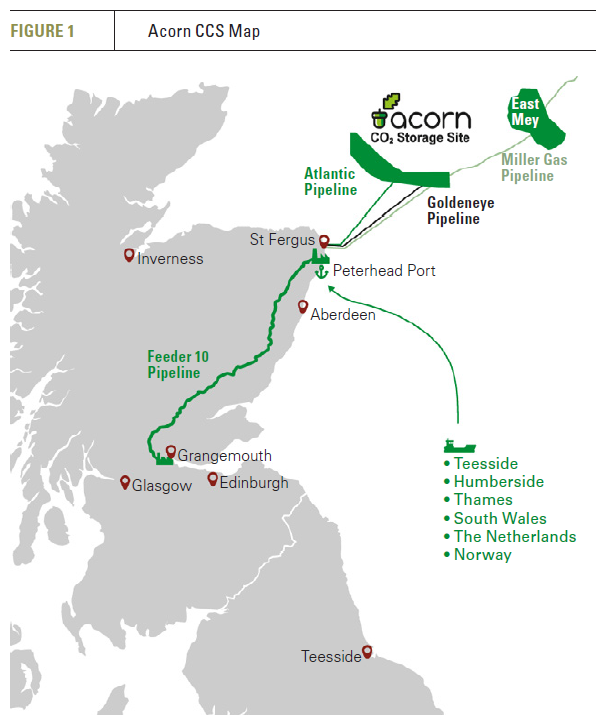

Another project that had been vying for funding was the Scottish Cluster, which centres around the Acorn CCS project in northeast Scotland. It is one of the most advanced CCUS projects in the UK, with a front-end engineering design study already underway. Yet the UK government has listed the Scottish Cluster as only a “reserve cluster”, meaning it will serve as a backup option if negotiations for one of the other two projects fall through.

“Whilst we are disappointed of the outcome of the sequencing bid, we remain convinced of the potential and significant advantages of the Scottish Cluster and are committed to the development of CCS to support decarbonisation of the UK industry and power,” Nick Cooper, CEO of Acorn CCS developer Storegga, said in an emailed statement to NGW. “We have been very clear that all of the current clusters need to be operating to meet UK net-zero targets and will be seeking support to progress as soon as possible.”

Prior to the government announcing the winning projects, Storegga had told NGW’s Gas Pathways that a final investment decision (FID) on Acorn CCS was expected as soon as early 2023, with commercial operations due to start two years later. But without state backing, the schedule is up in the air. Acorn CCS was expected to store up to 6.5mn mt/yr of CO2.

Reactions

Acorn will have another shot at state support further down the line, but the UK government’s decision to put it in reserve has provoked strong criticism from authorities in Scotland.

“This is a terrible decision by the UK government,” Scottish energy minister Michael Matheson commented on social media. “All credible evidence and analysis has demonstrated that CCUS is critical for meeting Scotland’s statutory emissions reduction targets.”

“This is a terrible decision by the UK government,” Scottish energy minister Michael Matheson commented on social media. “All credible evidence and analysis has demonstrated that CCUS is critical for meeting Scotland’s statutory emissions reduction targets.”

He added that the decision “will also significantly compromise our ability to take crucial action to reduce emissions in Scotland and will have serious implications for delivering a just transition for those in our oil and gas sector.”

Stephen Flynn, MP for Aberdeen South and the spokesman for the Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP) on business and energy matters, described the decision as “a catastrophic blow to Scotland’s net-zero ambitions and a betrayal of the north-east.”

Storegga and its partners at Acorn, Shell and Harbour Energy, intend to handle CO2 from nine primary emitters including Ineos, the owner of the Grangemouth refining and petrochemicals complex near Edinburgh. Ineos is targeting net-zero emissions by 2045, and was counting on Acorn to handle the 3mn mt of annual CO2 emissions emitted at Grangemouth, as well as to decarbonise areas like transport and home heating.

Since the government announced its selection, the company has unveiled a new plan to invest €2bn in green hydrogen production, which does not require CCUS but is more expensive than blue hydrogen. It wants to build electrolysers in Norway, Germany and Belgium over the next few years, and has additional projects planned for the UK and France.

Ineos has taken to the local press, stressing that CCUS will be vital for Scottish industry to survive in a net-zero landscape.

“In Scotland, if carbon capture does not go ahead, there will be no net zero or no industry at all,” Ineos told the Scottish Daily Mail. “Effectively it will lead to an export of jobs and the economy, whilst increasing imports and greenhouse gas emissions.”

The company said that without Acorn, the UK as a whole could struggle to realise its 2030 and 2050 emissions targets – a concern that was echoed by OGUK. The upstream association argues that the UK will need all five all CCUS cluster initiatives, which also include a second in the Humber region and one in the Southampton area, to hit net-zero. They boast a combined capacity of 100mn metric tons/year, which would be enough not only to decarbonise UK industry but also other sectors such as heavy freight and marine transport.

OGUK’s sustainability director Michael Tholen told the Scottish Daily Mail that a Scottish CCS project “could enable not just our oil and gas industry but also our chemical, refining, engineering and even our brewing industries to join the low-carbon economy.”

“With carbon capture, and the associated production of hydrogen, Scotland would risk another wave of deindustrialisation with key employers like the chemical industry moving south to new sites close to carbon capture facilities,” he said.