Russia deepens China ties with new gas deal [Gas in Transition]

Russia’s Gazprom announced on February 4 that it had signed a second long-term natural gas supply deal with China’s CNPC, taking advantage of the shift over the past year from a buyer’s to a supplier’s market for the fuel.

Since clinching its $400bn gas supply deal with CNPC in 2014, which underpinned the construction of the 38bn m3/year Power of Siberia pipeline, Moscow has had difficulty getting its Chinese partner to commit to taking any additional volumes via pipeline. This was partly because Chinese authorities felt that at least in the near term, the country could get the gas it needed in LNG form, and on a more flexible basis than piped imports.

Circumstances have altered radically over the past year, however, with LNG prices having risen to record heights in Asia, contributing to rolling blackouts in China last autumn. Recent events have renewed concerns about energy security in Beijing, and this may well have hastened negotiations with Moscow.

“Amid the continuing high volatility in spot gas prices, long-term gas supply contracts could be commercially beneficial both for suppliers and customers, because they generally provide higher stability of supplies and prices,” Artem Frolov, vice president and senior credit officer at Moody’s tells NGW.

What is more, the timing of the deal is politically favourable for both sides. Russia and China have both endured increasingly tense relations with the West over recent years, and are keen to strengthen their shared economic and political ties.

The new agreement covers 10bn m3/yr of annual supply over a 30-year period, not via Power of Siberia but via a new route to China from the Far East. Analysts expect deliveries could begin in two or three years’ time and reach a plateau by 2026.

A seller’s market

Price was a major sticking point in negotiations for the 2014 supply deal between Russia and China. Eventually, the two sides agreed on a price that was linked to oil, at what BCS Global Markets (BCS GM) estimates as an 8.5-9.0% slope at the countries’ border. Given present market conditions, though, the brokerage believes Gazprom likely fetched a better price under the new contract.

“Delivering gas to China's northeastern tip makes this project strategically attractive for China, as the only real alternative supply would be more expensive LNG," BCS GM oil analyst Ronald Smith tells NGW. "The global gas market is very much a seller's market today, so we expect Gazprom got pricing that is somewhat superior to [Power of Siberia supplies], perhaps with a 9-10% [slope]." This implies that if oil sells at $90/barrel, the gas will be priced at $300/'000 m3.”

“Delivering gas to China's northeastern tip makes this project strategically attractive for China, as the only real alternative supply would be more expensive LNG," BCS GM oil analyst Ronald Smith tells NGW. "The global gas market is very much a seller's market today, so we expect Gazprom got pricing that is somewhat superior to [Power of Siberia supplies], perhaps with a 9-10% [slope]." This implies that if oil sells at $90/barrel, the gas will be priced at $300/'000 m3.”

The arrangement is all the more favourable to Gazprom as the company will not have to pay transit fees to any third countries, which stack up to $70/’000 m3 to the price of gas it sells in Europe, according to BCS GM.

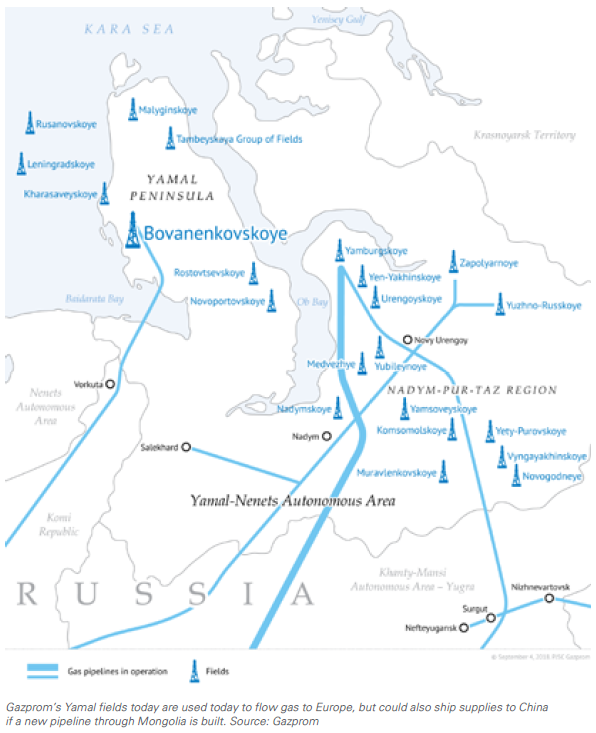

What is more, Smith believes there is a 50% probability that Gazprom’s negotiations for a further 50bn m3/yr of gas via a new pipeline to be built to China through Mongolia will lead to a deal within the next 12 months, given the project’s recent progress. Gazprom finished a feasibility study in late January on the pipeline, which would source its gas from the Russian Arctic.

Dmitry Marinchenko, senior director at Fitch, agrees that the market’s current tightness and Russia’s political difficulties with the West make the 50bn m3/yr deal with China more likely than before.

“However, there are many details yet to be worked out, including the price, before the project is formally sanctioned,” he tells NGW. “Getting everything agreed would take at least 1-2 years, and construction at least 3-4 years, which means that even if the project is accelerated, first gas is unlikely to flow before 2026-27.”

This pipeline is both a commercially and geographically attractive option for China, Kaho Yu, principal Asian analyst at Verisk Maplecroft, tells NGW. Rather than running across the country’s remote and restive northwest, where Russia had previously proposed running a pipeline through, it traverses a smaller distance to China’s heavily populated east seaboard. But having a transit country involved creates extra risk, he says.

This pipeline would link the Siberian gas fields that currently cater to European demand with the Chinese market. Initially Gazprom will be bound by supply contracts in either direction, Smith says, but over time, the connection will give it greater flexibility over where it sends its gas, and therefore greater negotiating power.

Gazprom is also in separate talks to ship an additional 6bn m3/yr of gas to China via the existing Power of Siberia.

Growing energy ties

It is only natural that Russia and China should share a close relationship in energy as neighbouring states, since the former is one of the largest hydrocarbon producers in the world and the latter is the biggest hydrocarbon importer. This relationship has been steadily expanding over the last decade.

The first landmark in this journey was the launch of the Eastern Siberia - Pacific Ocean (ESPO) oil pipeline system in 2011, which allowed Russia to pipe crude directly into China’s northeast, as well as export via tankers to China and other Asian markets. Following several expansions of ESPO, Russia today jostles with Saudi Arabia for the position of China’s top oil supplier. Last year alone it sent 1.59mn barrels/day of oil to the Chinese market, accounting for 15.5% of the country’s total imports, according to customs data.

Russia is also China’s third-biggest gas supplier delivering 16.5bn m3 of the fuel in 2021 via pipeline and in LNG form. LNG is dispatched via Novatek’s 17mn metric ton/year Yamal LNG plant in the Russian Arctic and Gazprom’s 11mn mt/yr Sakhalin LNG facility in the Far East. Power of Siberia, meanwhile, pumped 10.5bn m3 of gas to China last year, and is due to reach its full 38bn m3/yr capacity in the mid-2020s.

Russia has often courted Chinese investment for its upstream sector, especially since options for Western finance became more limited following Moscow’s annexation of Crimea and subsequent US and EU sanctions. But results have been mixed.

Rosneft, for example, had hoped to secure China’s CNPC as a partner at the Vankor oilfield in east Siberia, but in the end turned to Indian investors, while Gazprom had sought out Chinese support for Power of Siberia and the gas fields that feed it, but had to rely instead on its own funding as well as that of the Russian state.

Chinese investors have been more receptive to investing in Russian LNG, however. CNPC holds a 20% stake in Yamal LNG, while Beijing’s Silk Road Fund has 9.9%. CNPC and fellow Chinese state giant CNOOC went on to each take a 10% interest in Novatek’s 20mn mt/yr Arctic LNG-2 terminal, due on stream in 2023.

In addition, Chinese gas and power supplier Zhejiang Energy recently agreed terms to take a 10% stake in a prospective LNG project on the coast of the Far East, known as Yakutsk LNG, which is led by private investment firm A-Property.

China has also shown an interest in Russia’s burgeoning petrochemicals sector. State-owned oil firm Sinopec has a 10% interest in the country’s lead player in this sector Sibur, while Silk Road Fund also has a 10% position. In addition, Sinopec has bought a 60% interest in Sibur’s Amur gas chemical complex project, which will run on feedstock separated from gas that is running through Power of Siberia.

Supply arrangements

Gazprom did not go into details about what necessary upstream and midstream work would be needed to fulfil the new supply deal with CNPC. But in the past, it has indicated that the gas supply would come from the South-Kirinskoye gas field off the east coast of Sakhalin island.

South-Kirinskoye is one of several fields that comprise Gazprom’s Sakhalin-3 project. It was discovered in 2010, and is estimated by its operator to contain 711.2bn m3 of gas, along with 111.5mn metric tons of condensate and 4.1mn mt of oil in C1+C2 reserves. At full capacity, the field is projected to flow 21bn m3/yr of gas, easily providing what is needed under the Chinese contract.

Whatever excess supply at South-Kirinskoye could be used to supplement local demand in the Russian Far East. And Gazprom could also use it to underpin the contract of an LNG terminal in Vladivostok, enabling it to capture a larger share of the Asian gas market. Gazprom previously spoke of building an LNG terminal in Vladivostok comparable in size to its facility on Sakhalin Island, but several years ago it downsized the project to have a capacity of only 1.5mn metric tons/year.

The terminal would deliver LNG on a small-scale basis to nearby Asian markets, as well as provide bunkering services in a region where demand for LNG as a shipping fuel is increasing rapidly. Indeed, its location would make “fantastic sense – being just around the corner from the three largest LNG consumers in the world,” BCS GM’s Smith says.

To get to Vladivostok, and then onto China, gas from South-Kirinskoye must first flow via the Sakhalin-Khabarovsk-Vladivostok pipeline, which is currently undergoing an expansion to take its capacity up to 13bn m3/yr. But Smith notes that this could be raised further to 30bn m3/yr with the addition of extra compressor stations.

As recent events have demonstrated, the risk to Russia’s gas sales strategy is that market conditions are highly unpredictable, and a buyers’ market could re-emerge much faster than anticipated under most current forecasts. Once again, this would make it difficult for Gazprom and CNPC to find pricing terms they both deem acceptable. Emboldened by current high prices, LNG exporters are likely to accelerate a ramp-up in their capacity, increasing competition for Russia in China.

As recent events have demonstrated, the risk to Russia’s gas sales strategy is that market conditions are highly unpredictable, and a buyers’ market could re-emerge much faster than anticipated under most current forecasts. Once again, this would make it difficult for Gazprom and CNPC to find pricing terms they both deem acceptable. Emboldened by current high prices, LNG exporters are likely to accelerate a ramp-up in their capacity, increasing competition for Russia in China.

Beyond sales contracts, though, there is scope for additional partnerships between China and Russia. Development in the Russian Arctic is progressing and Moscow has increased fiscal incentives for projects there in recent years, making the region more attractive, Yu says. Possible recipients of Chinese investment include future Novatek LNG projects beyond Yamal LNG and Arctic LNG-2. Rosneft has also held talks on bringing on board Chinese investors at its Vostok Oil project, although no commitments have yet been made. But Yu cautions that energy investments still require lengthy negotiations.