Reform of EU’s electricity market [Gas in Transition]

The EU unveiled on March 14 plans for targeted reform of its electricity market. Central to these are long-term contracts between suppliers and consumers, that are expected to introduce greater certainty into the cost of electricity to consumers and spur much-needed investments in the renewables sector. The reform will result in revisions to EU’s Electricity Regulation, the Electricity Directive, and the Regulation on Wholesale Energy Market Integrity and Transparency (REMIT) – that provides a regulatory framework specific to EU’s wholesale energy markets.

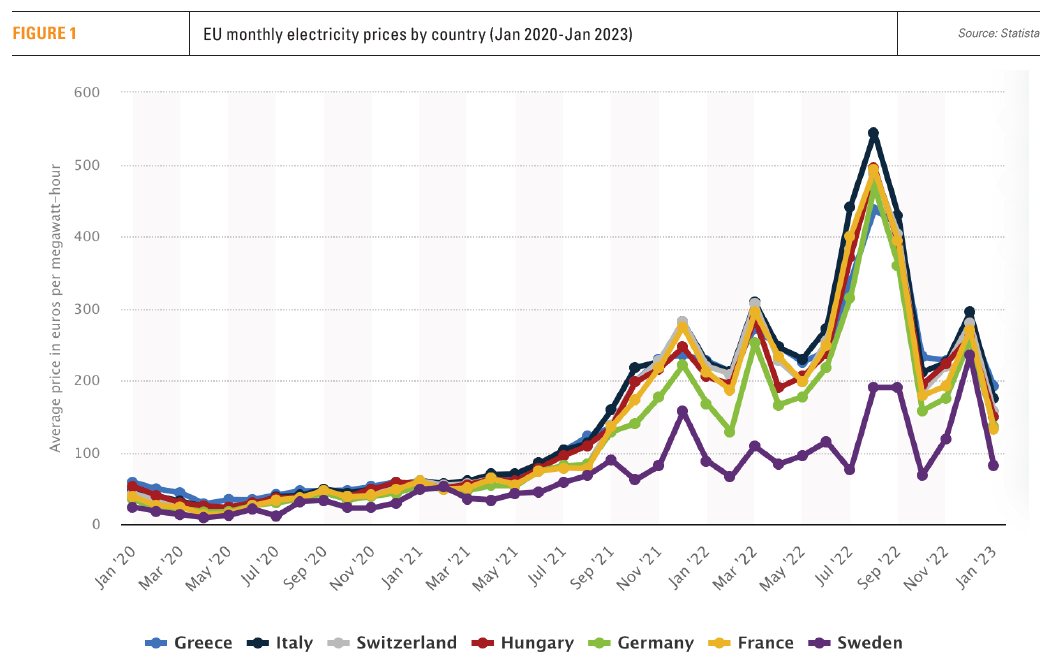

Ever since the energy crisis drove electricity prices to astronomical highs last year (see figure 1), with average day-ahead prices peaking at €405/MWh in August, the European Commission (EC) has been mulling various options to protect consumers from future price hikes. In coming up with its latest, targeted, recommendations, the EC avoided more radical proposals, favoured by France and Spain, such as separating electricity prices from natural gas prices, that would have rattled energy markets.

The EC appears to have heeded calls from a group of seven EU member states led by Germany, that urged the EC to focus on targeted and less ambitious reform measures.

Kadri Simson, the EC energy commissioner, confirmed that "the reform will not change the mechanics of price formation…But these volatile, short-term price developments will no longer determine to a large extent consumer prices." She added “It has become clear that we need to complement short-term markets with a more important role for long-term instruments to shelter consumers from price volatility and give credible price signals to renewable investors,” by “allowing them to buy electricity at predictable prices.”

The new proposals leave the ‘merit order’ system unchanged – the sequence in which power stations contribute power to the market, according to their respective generation costs. This was introduced in Europe in the early 2000s, as the basis of the liberalised electricity markets.

The EC hopes that the proposed reforms will eliminate future price spikes, especially as the share of renewable electricity grows from 37% in 2020 to over 65% by 2030.

Proposals

The EC is proposing three types of contracts, that, in various ways, are already being used in EU member states:

- Power Purchase Agreement (PPA): a private contract between a provider and a client, usually a company, that can last up to 15 years. It sets the terms for negotiated prices and supplies.

- Forward contract: a private contract between a provider and client, similar to a PPA but with a shorter duration of up to three years.

- Contract for Differences (CfD): a contract between a provider and the state that establishes a price range with minimum and maximum levels. If electricity prices fall below the range, the state compensates for the difference. But if the price exceeds the range, the state can recover the surplus revenues.

CfDs will become mandatory for all new renewables and nuclear energy projects that receive national subsidies. CfDs and PPAs have been proposed to give stable prices to consumers and reliable revenues to renewable energy suppliers. The EC believes that the introduction of these contracts will enhance the competitiveness of EU industry and to reduce its exposure to volatile prices.

Kadri Simson said “Contracts for difference will cover low-carbon or renewable installations and allow them also to promote future investments in these production units.” This implies that the reformed EU power market could support low-carbon energy like nuclear power, favoured by France, in addition to renewables.

The reform also provides that should prices go up, resulting in windfall profits by low-carbon generating companies, EU governments will be legally required to redirect these to support households and industry.

It also includes ‘a right to choose’, that will allow consumers to have multiple contracts, fixed-price as well as variable, at the same time for different purposes. In addition, ‘right to share’ rules will make it possible for consumers to invest in wind or solar parks and sell excess rooftop solar electricity to neighbours, not just to their supplier. The EC says consumers will have the option to lock-in secure, long-term prices to avoid excessive risks and volatility.

The proposals include demand-side measures that allow grid operators to encourage cuts in consumption at peak times, when the most expensive power plants are called in, such as those running on gas.

The EC proposes a ‘crisis mechanism’, to enable it to declare an EU-wide crisis should electricity prices rise dramatically and remain high for at least six months. This would allow member states to “artificially regulate retail tariffs for households and SMEs.”

In support of these proposals, the EC has issued recommendations on the advancement of storage innovation, technologies, and capacities.

The EC believes that through these contracts, investors will obtain the necessary guarantees that their investments will pay off and yield steady benefits.

The reform is not meant to eliminate price fluctuation, but to protect consumers against price spikes.

The next step is for the reform to be discussed and agreed by the European Parliament (EP) and the Council before entering into force. Kadri Simson requested the EP to give this top priority.

What the EC aims to achieve

The EC hopes that the reform will “accelerate a surge in renewables and the phase-out of gas, make consumer bills less dependent on volatile fossil fuel prices, better protect consumers from future price spikes and potential market manipulation, and make the EU's industry clean and more competitive.”

In order to achieve these ambitious goals, the EC introduces measures, such as demand response and storage, that incentivize longer-term contracts with low-carbon power production and promote more clean flexible solutions to compete with natural gas.

In order to achieve these ambitious goals, the EC introduces measures, such as demand response and storage, that incentivize longer-term contracts with low-carbon power production and promote more clean flexible solutions to compete with natural gas.

As the share of renewable electricity increases, the reform aims to reduce the impact of fossil fuels on consumer electricity bills, as well as ensure that these reflect the lower cost of renewables. It is also expected to boost open and fair competition in the European wholesale energy markets by enhancing market transparency and integrity.

In order to make sure markets are competitive and price-setting is transparent, “REMIT will ensure better data quality as well as strengthen ACER's role in investigations of potential market abuse cases of cross border nature.” The EC hopes this will step-up the protection of EU consumers and industry against any market abuse.

In parallel to the proposed reform, EC has put forward a new package of legislation, the Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) and European Critical Materials Act (CRMA), that aims to create better conditions for energy transition projects and reduce reliance on imports, including critical minerals. Through these, the EC hopes to accelerate deployment of clean technologies in the EU, particularly renewables, hydrogen and carbon capture and storage.

Challenges

There are many who are relieved the proposed reform does not include some of the more radical proposals that were put forward during and after the energy crisis. With prices down, pressure on the EU's energy market has relaxed, doing away with calls for such radical change.

However, there is concern that the reform is being rushed through, to the extent that Europe could take fundamental decisions for the future of its electricity system without full understanding of the consequences. As Bruegel points out, “CfDs can create operational distortions as generators are guaranteed a fixed price for their output, regardless of the system conditions at the time.” In the past, “the PPA market has struggled to match supply and demand.”

In addition, the reform encourages more state involvement in the electricity system, but in an uncoordinated way, as there is no “mechanism to ensure a basic level of consistency of national choices,” and how to deal with “ill-designed national schemes.

To counter this, sufficient time should be given to the political discussion process in order to ensure a thorough assessment of the impact of the reforms and the role of electricity markets during the energy transition. Bruegel recommends phased reforms.

Despite the fact that energy and electricity prices have come down considerably since their peak last year, they are still too high in comparison to pre-COVID prices, impacting consumer affordability and EU industry competitiveness. In the meanwhile, while low-carbon energy generators are earning record profits, they are not investing sufficiently in the technologies needed to decarbonise the power system. Governments, consumers, businesses and industry expect the reform to address these issues fairly.

As the International Energy Agency and Bloomberg NEF pointed out in recent reports, investments in low-carbon technology must increase by at least a factor of 3 and repeated every year if the world is to get back on track to achieve net-zero by 2050.

Another challenge, that the reformed electricity market should accommodate, is that even though the share of gas in power generation may decline as energy transition progresses, it still provides crucial flexibility to meet electricity demand, especially during periods of low wind and solar availability, as well during periods of drought that affect hydro and nuclear generation. With climate change affecting Europe’s climate, such conditions occur more often and last longer. Until clean energy technologies are developed to address these challenges and long-term intermittency, and provide secure and reliable energy, gas will continue to be an important part of the transition process, well beyond 2030. In effect intermittent supply adds to the challenge of balancing the grid, requiring more gas for back-up.

Criticism of the proposed reform came from Germany’s renewable industry association (BEE), which said it goes too far, especially the proposal that future subsidies for low-carbon electricity generation would have to be made through CfDs, and called for the delegation of more decision-making power at national level.

Energy companies, including Engie, Orsted and Iberdrola, have warned that making CfDs mandatory could deter investment. However, Eurelectric, the federation of the European electricity industry, appears to be generally supportive.

The urgency now is to get the proposed reform through the EU's legislative process before the European elections next year. This will require majority support at the EP and a reinforced majority of at least 15 states at the European Council. Failure to do so could delay the reforms significantly. The limited time available perhaps explains why the proposals are less radical than expected. That means that broader reforms may be needed in future.