Project spotlight: Qilak LNG [Gas in Transition]

Getting its natural resources to market has always been a struggle for Alaska. Huge oil finds eventually necessitated construction of the 800-mile Trans-Alaskan Oil Pipeline, a major feat of engineering completed in 1977. The pipeline brings oil from the state’s prolific North Slope to the ice-free Valdez Marine terminal for onward shipment. Oil production in the state peaked in 1988 at 2 mn b/d, but, by 2021, had declined to 437,000 b/d.

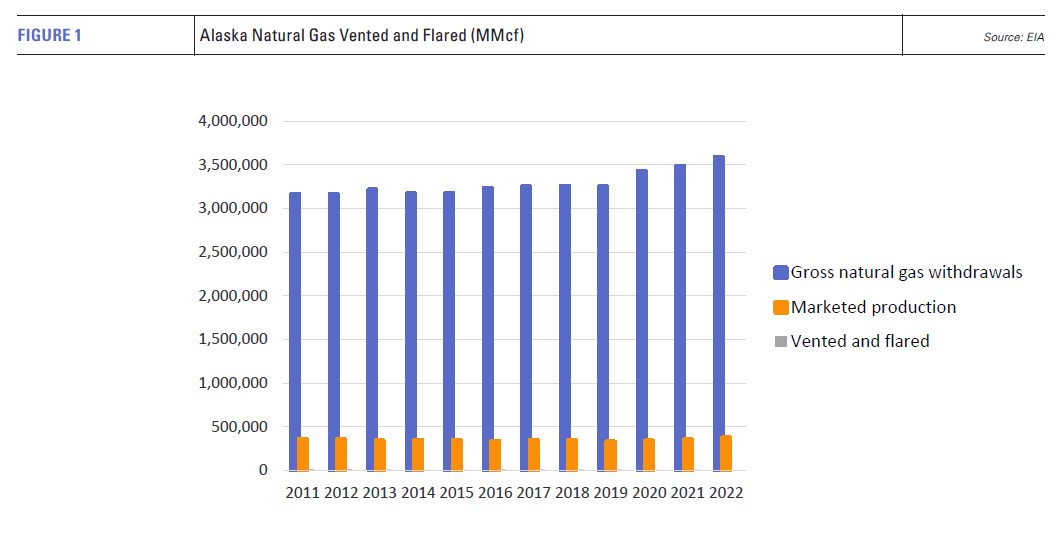

Getting gas to market has been even more problematic, owing to its lower value and the distances involved. In fact, Alaska is a large gas producer. It had proved reserves of 37 trillion ft3 at the start of 2021 and last year gross withdrawals totalled 3.5 trillion ft3, close to record levels. Gas production has been on a gentle upward trend in recent years, as oil output falls.

Yet less than a fifth of production reaches end-consumers. The majority, about 83%, is used in the oil and gas production process, in particular being used as reinjection gas to maintain reservoir pressure. Only a small amount is flared or vented – 0.17% in 2021, according to US Energy Administration Data.

Nonetheless, natural gas is important to the Alaskan economy. It generates around 40% of the state’s electricity, which accounts for about 6% of total gas production, while the residential, commercial and industrial sectors consume a further 11%. Almost half of all Alaskan homes use gas for heating. Even so, local demand is nowhere near the level of production.

Plans to utilise Alaska’s gas resources more fully are long-standing and the concept of LNG exports is by no means alien. The small-scale Kenai LNG plant on Cook Inlet exported LNG from 1969 through to the mid-2010s. However, Cook Inlet is far from the North Slope. Its own ageing oil and gas fields supply the Railbelt area, but are insufficient to sustain a large-scale LNG plant.

A 1,300-km gas pipeline to bring gas to Valdez has also been much discussed, but it would be expensive and face considerable environmental opposition.

Moreover, the advance of Arctic oil and gas technology has made other options possible and it is this which the Qilak LNG project aims to capitalise on. Rather than transport gas hundreds of miles to an ice-free port by pipeline, LNG could be produced directly on the North Slope, taking advantage of Arctic temperatures to reduce energy inputs into the liquefaction process.

The first phase of the project is planned at 4mn metric tons/year capacity. It would source gas from existing infrastructure, linked to 32.4 trillion ft3 of proven reserves. Qilak LNG has already signed a memorandum of understanding with US oil major ExxonMobil for gas supply from the Point Thomson field for the first phase. An earlier stage agreement put the promised volumes at 560mn ft3/d.

Arctic class LNGCs

While producing the LNG on the North Slope avoids construction of a long pipeline, it will require ice-breaking LNG carriers (LNGCs). However, the Aker Arctic LNGC design (Arc7) has been tried and tested with Russian company Novak’s Arctic Yamal LNG project. The vessels have a bow tailored for sailing in open waters and moderate ice conditions plus a heavy stern capable of ice breaking using three azimuth propulsion units. Plans are to load 3-5 Arc7 LNGCs per month.

The Arc7 carriers designed for Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2 project are even more powerful than those deployed for Yamal LNG. The vessels have a new hull design and 51 MW of power, almost as much as Russia’s latest generation of nuclear-powered icebreakers of the Arktika class, in order to deal with the challenging conditions in the East Siberian Sea in the winter months. They are expected to be capable of navigating Russia’s Northern Sea Route year round without icebreaker escorts.

Arc7 LNGCs were ordered in 2020 for Novatek by Japan’s MOL and Russia’s Sovcomflot from Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering at a reported $280mn each. Fast forward to October 2022 when shipping consultants Drewry put the cost of a newbuild non-Arctic class LNGC at $250mn plus, a rise of 25% over nine months with no shipyard slots available until 2026. A fleet of Arc7 LNGCs will therefore not come cheap.

Harsh environment liquefaction

The LNG plant itself will be a near-shore facility, hosting the liquefaction machinery, storage capacity and offloading arms to serve the Arctic-class LNGCs. It will be a gravity-based structure connected to the Point Thomson field by a six-mile pipeline. A gas conditioning plant will be located onshore at Point Thomson.

The plan is to use modern gravity-based structures (GBSs), similar to those deployed by Novatek on its Arctic LNG 2 development. GBSs are also planned for Novatek’s proposed Ob LNG.

GBSs are by no means new. According to UK oil major Shell there are 42 GBS in the world. They were originally designed for the harsh conditions of North Sea oil production and consist of huge ferro-concrete legs capable of supporting heavy processing facilities offshore. At their base are storage cells. The Brent field, for example, has 64 storage cells in three giant GBS, each of which weighs 300,000 mt. They preceded development of a North Sea pipeline network, so that oil could be produced, stored and loaded onto tankers from isolated offshore processing facilities.

Competitive offering

Given the far western location of Qilak LNG, distances to northeast Asian LNG markets will be short in comparison with competitors, notably US facilities located in the Gulf of Mexico, which have the additional cost of traversing the Panama Canal to access the Pacific. Transits to northeast Asia are expected to take about 14 days, about twice as fast as from the US Gulf Coast. Qilak is also 2,000 nautical miles (3,700 km) closer to Asian markets than Yamal LNG.

Although comparisons are usually drawn with Russia’s Arctic LNG projects, being situated in Alaska arguably makes the under construction LNG Canada project Qilak’s primary competitor.

Although comparisons are usually drawn with Russia’s Arctic LNG projects, being situated in Alaska arguably makes the under construction LNG Canada project Qilak’s primary competitor.

Yamal LNG is estimated to have cost $27 billion for 16.5mn mt/yr capacity. Costs for Arctic LNG 2, which used GBS for the first time in Russia, built by Italy’s Saipem, have been put at about $21bn for 19.8mn mt/yr capacity. Qilak phase one is estimated at $5bn for 4mn mt/yr.

On a $/mt capacity basis, this works out at Yamal $1,630/mt; Arctic 2 $1,060/mt; and Qilak $1,250/mt. However, the final costs for Arctic LNG 2 are uncertain, following the withdrawal of western investors and technology companies in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Qilak is also being proposed after a period of rapidly rising raw materials costs, while Yamal and Arctic 2 were completed or started before this.

In contrast, Canada LNG will have 14mn mt/yr capacity, but costs have skyrocketed to around $48bn, including the plant itself, annual budgets for drilling in the North Montney region and the seemingly ever rising costs of the Coastal GasLink pipeline, which are now put at $14.5bn alone.

As such, if Qilak can deliver on its cost projections, it looks competitive and should benefit from relatively low operating costs. Higher investment in Arc7 LNG carriers should be offset by this and the short transits to market.

Limiting the plant’s greenhouse gas emissions may also prove difficult, as the option, as at LNG Canada, to use a high proportion of renewable energy for electrically-driven compressors doesn’t exist. However, the North Slope’s oil and gas fields should provide a nearby opportunity for carbon dioxide reinjection, either for permanent sequestration or to support oil field production.

The project is being developed by Lloyds Energy, a company led by former Governor of Alaska Mead Treadwell. According to Treadwell, the company hopes to complete a feasibility study this year and front-end engineering design in 2024. A final investment decision, which will almost certainly depend on landing off-take agreements for the majority of the development’s first phase output, could be taken in 2025 for commercial start-up in 2030.