Oil, gas and the transition [NGW Magazine]

Τhe International Energy Agency (IEA) presented its report on the ‘Oil and Gas Industry and Energy Transition’ at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting at Davos.

Introducing the report January 21, the IEA said that demands were mounting for the industry to say how it was addressing the threat of climate change.

IEA executive director Fatih Birol said every energy company will be affected and every part of the industry must respond to these demands. “Doing nothing is simply not an option,” he said.

It says oil and gas companies that put short-term profits ahead of curbing their upstream emissions would endanger their social licence to operate.

But excluding energy companies from the policy-making process is not the answer either. This needs to be redressed because, as the IEA report makes clear, the role of these companies is central to the success of the energy transition.

Key findings

The key findings from the report are:

- The oil and gas industry must balance short-term returns with long-term licence to operate.

- Every part of the oil and gas industry needs to consider how to respond to clean energy transitions. This should include not just the majors, but all national and international oil companies (NOCs, IOCs).

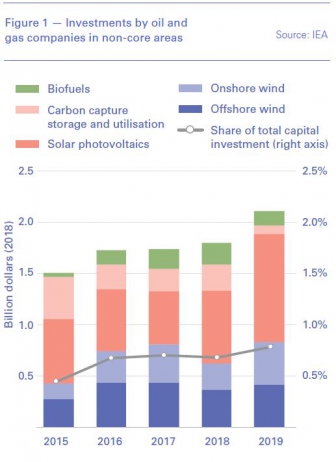

- Investments in low-carbon businesses represent less than 1% of oil and gas companies’ capital expenditure. This is nowhere near enough.

- Reducing the environmental footprint of the oil and gas industry includes cutting flaring of associated gas and venting of CO2; tackling methane emissions; and integrating renewables and low-carbon electricity into new upstream and LNG developments.

- Electricity cannot be the only vector for the energy sector’s transformation. It should include bringing down emissions from core oil and gas operations and stepping up investment in low-carbon hydrogen, bio-methane and advanced biofuels.

- A fast-moving energy sector would change the game for upstream investment, by concentrating investment on low-cost resources, with tight control of costs and environmental performance.

- A shift from ‘oil and gas’ to ‘energy’ provides a way to manage transition risks by moving into cleaner sectors, such as electricity that provides long-term opportunities for growth.

- NOCs face some particular challenges, as do their governments and societies that often rely heavily on the associated oil income. Reform and economic diversification have become essential.

- The oil and gas industry will be critical for key capital-intensive clean energy technologies to reach maturity, for example the development of carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS).

Sustainable development

In 2019 oil and gas companies invested just $2.1bn in solar, wind, biofuels and carbon-capture projects, amounting to about 0.8% of their total capital expenditures.

The IEA suggests that the sustainable way forward is to balance the oil and gas companies’ desire for near-term financial returns and a long-term future, by playing a much larger role in combating the climate crisis.

Pressure is already increasing on oil and gas companies to reduce the environmental footprint of their operations. The report points out that around 15% of global energy-related GHG emissions come from the extraction and delivery of products to consumers and “a large part of these emissions can be brought down relatively quickly and easily.”

This includes lowering the emission intensity of delivered oil and gas; eliminating routine flaring; and integrating renewables and low-carbon electricity into new upstream and LNG developments.

Responding to the pressure on them, some of the world’s biggest oil and gas companies, including Shell, Chevron, Total, Saudi Aramco and BP, discussed adopting much more ambitious carbon targets at a closed-door meeting in Davos January 22. This included widening the industry’s target to include reductions in emissions from the fuels they sell, not just the GHG gases produced by their own operations, and there was, unconfirmed, broad agreement on the need to move toward the Scope 3 definition. Targeting Scope 3 emissions would be a big shift for an industry that accounts for the bulk of GHG emissions.

In a bid to catch up with Shell, and in response to increasing investor pressure, BP’s next CEO Bernard Looney plans to expand the company’s climate targets and is considering overhauling the structure of BP in one of its biggest shake-ups in its history.

Risks

Foremost is the risk of stranded assets.

The IEA states that NOCs account for over 60% of global oil and gas reserves but they are not well-prepared for the energy transition.

In many countries oil and gas revenues contribute more than half of fiscal revenues and if the world takes a more aggressive approach to climate action, some of these assets could become uneconomic. The risk of stranded volumes is “significantly higher” for NOCs than it is for IOCs.

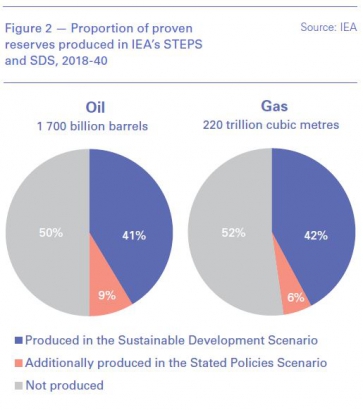

In addition, one way or another, large volumes of proven reserves will be “kept in the ground”, as many of these would not be produced before 2040 under any of IEA’s scenarios (Figure 2).

A disjointed transition, with a sudden surge in the intensity of climate policies, could lead to over-investment in the wrong kind of assets, or in sectors deemed ‘safe havens’ in energy transitions, notably natural gas and petrochemicals. This may be already happening with natural gas liquefaction. Financial institutions – notably the European Investment Bank – are pulling funding from many kinds of fossil fuel projects.

Also important are investment strategies and the risk of over- and/or under- investment in ways that would have strong implications for markets and public policy. Under-investment in oil and gas could result in future production lagging demand.

There is also a fundamental reshaping of finance and the risks this poses to future energy investments. BlackRock, which manages $7 trillion assets, shows the extent to which climate change has become a defining factor for such investors. Writing in January, its CEO Larry Fink said: “The evidence on climate risk is compelling investors to reassess core assumptions about modern finance... And because capital markets pull future risk forward, we will see changes in capital allocation more quickly than we see changes to the climate itself... Every government, company, and shareholder must confront climate change… Where we feel companies and boards are not producing effective sustainability disclosures or implementing frameworks for managing these issues, we will hold board members accountable.”

Strategic responses

The key priority for the oil and gas industry must be to address carbon emissions by clamping down on methane leaks and reducing the environmental footprint.

Other choices include integrating solar and wind projects into upstream developments; and investing in renewables and electricity generation, biofuels and in CCUS.

Birol said oil and gas companies can use their "extensive know-how and deep pockets" to play a "crucial role" in the deployment of offshore wind while also supporting the development of new technologies. “Without the industry’s input these technologies may simply not achieve the scale needed for them to move the dial on emissions," he said.

Development of CCUS technology is already benefiting from oil and gas company investment. This should be extended to hydrogen, biofuels, biomethane and advanced bio-refineries. The IEA says that within a decade, alternative fuel spending must account for at least 15% of total investments in the fuel supply to help combat the growing threat of climate change.

Going further, the IEA report states that the cost of developing these technologies should be considered as an investment in the ability of the oil and gas companies to prosper in the long-term.

As the IEA recommends, the industry would benefit from strong and unambiguous direction from policy makers. There is ample room for greater clarity on how energy and climate policies will evolve.

Transition from ‘fuel’ to ‘energy’ companies

The IEA points out that the oil and gas industry is largely unique in having the financial resources and large-scale engineering and project management capabilities to transit from ‘fuel’ to ‘energy’ and thus to drive many of these new industries to the point where they can deliver meaningful emissions reduction.

The IEA considers this transition essential. One of its key conclusions is that “transformation of the energy sector can happen without the oil and gas industry, but it would be more difficult and more expensive.” It also adds that “a commitment by oil and gas companies to provide clean fuels to the world’s consumers is critical to the prospects for reducing emissions.”

The IEA accepts that transition from ‘oil and gas’ to ‘energy’ will take companies out of their comfort zone. But it points out that with consumer spending on electricity forecast to overtake that of oil, it could also provide a way to reduce transition risks.

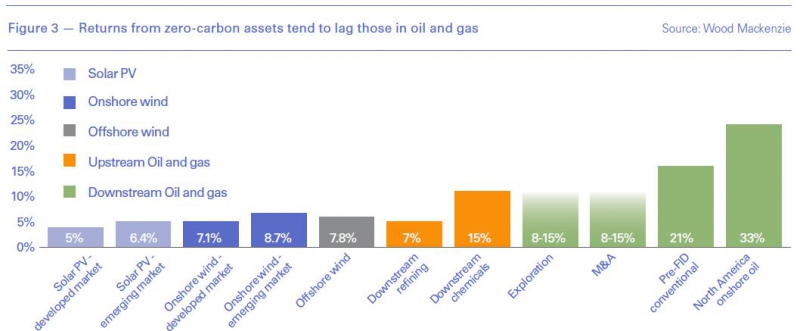

Oil and gas companies will have to prepare for a changing world, where public opinion about fossil fuels is growing more hostile and competition, regulation, and geopolitical factors make for a more volatile financial outlook. This is a fundamental challenge for an industry that has grown used to largely predictable and profitable returns (Figure 3).

The answer may be through acquisition or creation of daughter companies, which can evolve into businesses of the scale necessary to take on a global market – such as zero-carbon energy.

One consequence of the energy transition is that the world has entered an era of abundance, with the result that the market is becoming much more competitive and cost-driven – as well as harder to manage from a grid operator’s perspective.

Impact on natural gas

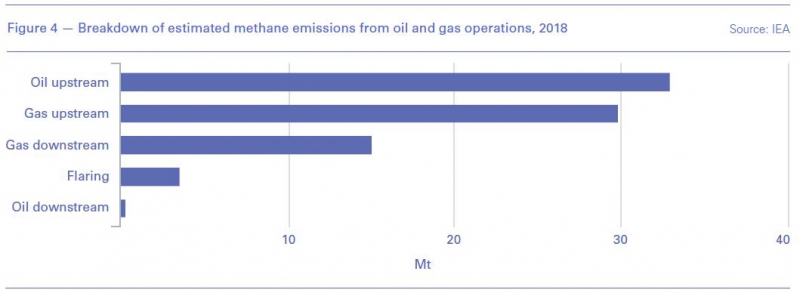

The IEA states that “gas is one of the mainstays of global energy. Where it replaces more polluting fuels, it improves air quality and limits emissions of carbon dioxide.” Reducing methane leaks (Figure 4) is the single most important and cost-effective way for the gas industry to bring down emissions and improve its image and prospects.

As the transition progresses, oil and gas companies will still need to continue to focus on natural gas and oil as key markets, as demand for these products is expected to remain strong in the coming decades. Demand for hydrocarbons in fast-growing economies is robust.

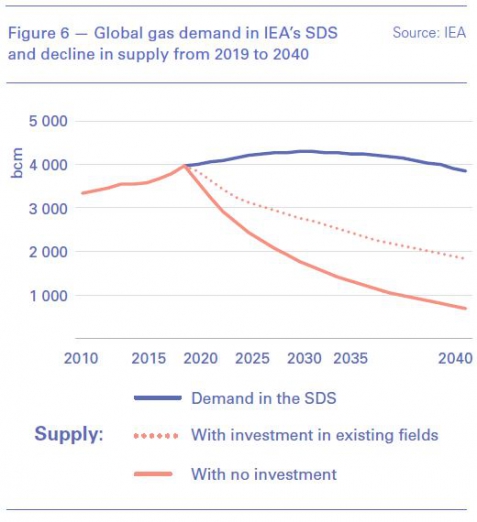

As Birol pointed out, under IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) investment in oil and gas projects will still be needed (Figure 5), even in rapid clean energy transitions. If such investment were to stop completely, the decline in output would be around 8%/year (Figure 6), which would be “larger than any plausible fall in global demand, so investment in existing fields and some new ones remains part of the picture.”

As overall investment falls back and markets become increasingly competitive, only those gas-fields with low-cost resources and tight control of costs and environmental performance will be in a position to benefit.

DNV-GL says in a new outlook report on the oil and gas industry this year that the emphasis on decarbonisation means companies must exploit synergies and a partnership of renewables with gas is the ideal scenario.

But clarity is needed from the EU and governments on future regulations and this may come from the European Green Deal, expected to be ready by March.

European Commission studies show possible reductions in unabated gas of up to 20% by 2030, rising to between 75% and 85% by 2050, as fossil gas gradually gives way to carbon-free gases and hydrogen. The new European Union’s commissioner for energy Kadri Simson said mid-January: “In the future we have to focus on electrification. And gas should not be natural gas any more, but green gas like biogas or hydrogen.”

Challenges

One way or another energy transition to a net-zero carbon future will reshape economies and societies globally. Whichever way the world goes, intensifying climate events are increasing the pressure on the energy industry and governments to act.

In addition, as the IEA points out “the nearing of the Paris Agreement 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will increase the pressure on all industries to find solutions to their production of emissions.”

But the dual challenge oil and gas companies face is that society simultaneously demands uninterrupted and reliable energy services, but also reductions in emissions. Giving too much weight to one and not balancing the other is prone to risks.

The IEA warns that “overall, there are few signs of the large-scale change in capital allocation needed to put the world on a more sustainable path.”

Under pressure from activists and shareholders to increase action to combat climate change, IOCs are generally responding, especially those in Europe. And even though at present this response is slow, it is picking up. But this is far from being the case with many NOCs. This may lead to a bi-polar world, with IOCs increasingly reinventing themselves as ‘energy’ companies, with the lower returns that implies; while some low-cost NOCs can carry on with business-as-usual, shielded by their governments and reaping the benefits without contributing to energy transition.

However, with oil and gas expected to be needed well into the future, even up to 2050, investment in the industry must continue. There must be a balance between delivering energy transition while still providing the oil and gas supplies the world will need. While, at the same time, still delivering the dividend payments their investors expect. It is a delicate balance that, with strong activism and shareholder pressure, may at times be difficult to maintain. But it will affect IOCs more than NOCs, with the latter increasingly becoming the ‘fuel’ providers to the world – particularly the developing world.

However, a recent survey of oil and gas professionals by DNV-GL has produced encouraging results. About 71% of respondents – compared to 54% in 2019 – expect their companies to increase or maintain investment in decarbonisation, despite volatile market conditions.

As DNV-GL says: “Significantly, they [companies] are pursuing multiple routes, including diversifying into renewable energy, decarbonising oil and gas production, and increasing investment in decarbonised gas such as hydrogen.” More and more people are realising that the industry must take matters into its own hands.