Oil: dead on the water? [NGW Magazine]

The social impact of the pandemic may mean there is no return to the energy demand trajectory which existed pre-Covid-19. But once the smoke has cleared, governments will have to decide whether to use fiscal stimuli to accelerate the energy transition or simply to jump-start the economy at the lowest cost.

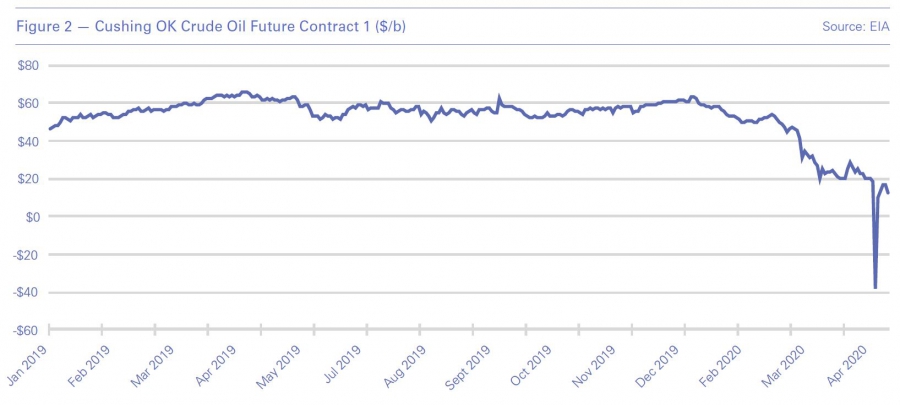

The oil market has experienced a series of entirely new events in the space of just a few months: the market was flooded with oil as a result of the breakdown in talks between Russia and Saudi Arabia and then demand vanished as a result of the coronavirus (Covid-19).

The profound price collapse even led to negative prices in the US – in effect producers having to pay to have their crude taken away. Regardless of the major output cuts agreed by the Opec+ group, oil producers are scrambling to cut production of a commodity to limit their losses. Norway too has joined in, for the first time in almost two decades, announcing at the end of April it would cut production by 250,000 b/d in June and by 134,000 b/d during the second half of the year.

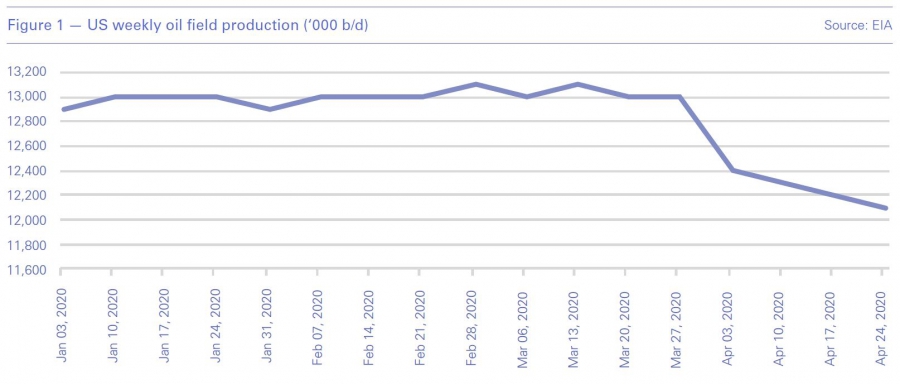

US field production of crude oil dropped from 13mn b/d in January to 12.1mn b/d for the week ending April 24. The US oil rig count has slumped from 670 at the start of the year to just 325 on April 1, according to Baker Hughes. The gas rig count has dropped from 123 to 81. This level of activity is on a par with the autumn of 2016, but both counts are likely to continue their freefall.

The US Energy Information Administration puts dry shale gas production and US gas output on a downward trend from February. Reduced oil output will cut associated gas volumes.

Global impact

The International Energy Agency’s Global Energy Review 2020, published in April, illustrates the impact on energy demand in the first quarter of 2020 (see separate feature, Page ??).

The IEA estimates that at end-March, global transport activity was almost 50% below the 2019 average with aviation 60% below while electricity demand for countries in full lockdown has fallen by 20% or more.

This has hit fossil fuel generation harder than renewables because even if fossil fuel prices are low, they cannot compete with free input energy. Renewable generation capacity continues to increase and in many countries around the world it benefits from priority dispatch on preferential terms. As demand falls, must-run renewables’ share of generation increases substantially.

On average across the year, oil demand could fall 9% – roughly 9mn b/d – putting consumption back to 2012 levels. For April, the IEA estimates that oil demand was down an incredible 29mn b/d compared with April 2019 and it expects demand to remain 2.9mn b/d below year earlier levels even as late as December.

At the beginning of May, lockdown restrictions were beginning to be eased, despite fears that infection rates may again rise. If they do not, this should allow a gradual recovery in economic activity, but not to former levels. Many businesses will not reopen and forecasts for aviation suggest demand will remain subdued for some time. Those businesses that do reopen will face very tough trading conditions and many furloughed staff will find they have no job to return to.

According to the International Monetary Fund, the world economy will contract by 3% this year. Advanced economies are expected to shrink by 6.1% in contrast to a 1.0% fall overall for emerging markets and developing economies.

Rebalancing

It will take a long time for the oil market to rebalance, suggesting low prices in the short and medium term. Its immediate problem is a lack of storage: the IEA estimates that floating storage of crude jumped in March from 22.9mn barrels to 103.1mn barrels, or a whole average day’s demand last year. By early May, another calculation put the figure at 170mn barrels afloat.

The IEA expects global oil supply to fall 12mn b/d in May, owing to the deal reached amongst the Opec+ group and market driven cuts in non-Opec oil supply. The IEA expects non-Opec output to fall as much as 5.2mn b/d by fourth-quarter 2020 and to be on average 2.3mn b/d lower for the year as a whole.

Oil prices will remain depressed until the huge and still building stock of surplus inventory is drawn down gradually by low demand. Stocks levels, in terms of forward demand coverage, are even higher than their absolute levels suggest.

Surplus capacity

Drawing down stocks is just the start of the rebalancing process. The oil market will emerge from its bout of Covid-19 with huge surplus capacity spread much more broadly than before.

Before, the world’s surplus oil capacity was concentrated in Saudi Arabia with some additional capacity held by other Middle Eastern producers. This allowed Saudi Arabia a measure of market control, accentuated by the degree to which it could persuade other producers within Opec and without (Opec+) to co-operate.

Post-Covid-19, almost all Opec+ members and major non-Opec producers such as the US will also have spare production capacity. This is a new situation.

Opec has always faced the dilemma that its output curbs, in supporting oil prices, provide a free pass to non-Opec producers, a situation exemplified by the rise of US shale oil.

That problem will be even more acute. As the oil price stabilises thanks to recovering demand, output cuts and the gradual drawdown of stocks, the Opec+ group should eventually be able to recapture former market share or push prices higher, but they will not be able to do both, as one objective will come at the expense of the other.

This time, Opec and its associates will have to contend not just with the possibility of reviving the US shale sector, but other non-Opec spare capacity coming back to the market.

Investment halt

The other side of the coin is the impact on oil and gas investment. With surplus capacity across the board and revenues sharply lower, hit both by prices falls and reduced volumes, oil and gas companies, whether state-owned or private, will find themselves with neither the cash nor incentive to invest in new capacity.

Without frequent attention, oil and gas fields decline over time and with little new investment, decline rates tend to trend upward. There is no reason to spend money squeezing every last barrel out of a field when prices are low and there is no shortage of crude. This is another longer-term form of supply-rebalancing.

The backwash will be felt profoundly by the oil services companies. Low oil and gas prices will mean a new round of cost -cutting and efficiency drives which should again lower the marginal cost of new oil production.

Gas markets

This low oil price outlook will have profound impacts on gas markets. The International Gas Union’s survey of gas pricing published last year showed further gains in gas-on-gas competition across the world, but the reduction in oil price indexation overall was geographically very uneven. In Asia, the share of gas linked to oil price escalation has been on an upward trend and stood at two thirds in 2018, compared with a third in 2005.

In its 2020 annual report, the IGU said that in 2019 about 68% of LNG volumes sold through long-term contracts (about two-thirds of the LNG market) were indexed to oil, while 24% were indexed to Henry Hub. The increase in spot LNG trade in 2019 should reduce this, but it remains unclear how the market will adapt to the new realities.

There has been some concern that buyers will invoke force majeure clauses, as a means of exiting long-term contract obligations. But no seller has ever yet conceded, and there are no cases of FM clauses being successfully used to relieve an LNG buyer – in the public domain at least (see box). Pushing long-term contracted LNG out into the spot market will keep downward pressure on prices, which sellers are unlikely to agree to. Equally, with the oil price likely to stay in the doldrums from some time, long-term oil-indexed contracts should deliver low-cost LNG.

However, whether the LNG market and gas more generally can return to its former growth rates depends critically on demand. The LNG market was in surplus going into the pandemic with a full supply chain of new US LNG plants still to come on line, the latest to do so being Freeport LNG’s third and last train on May 1.

The expectation, or hope, had been that the availability of low-cost LNG would stimulate demand in growing Asian economies and underpin a global shift away from coal-fired generation to gas and renewables, reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

This demand growth will be held back by recession at a time when liquefaction capacity had already extended itself beyond the world’s pre-Covid-19 requirements.

The composition of recovery

Pre-Covid-19, oil demand on average was only expected to grow by just over 1%/yr out to 2040. If there is a structural downward shift in transport demand, for example, as a result of recession or more fundamental changes in behaviour – for example increased home working, reduced business travel or a decline in tourism – it could be enough to see not just a short-term collapse in oil demand but slower than expected growth over the longer term.

Peak oil demand, expected sometime after 2030 by many forecasters, including major oil companies such as BP and Shell, could come sooner than expected.

Governments across the world are offering cheap or free debt in an effort to kickstart their economies. At the same time, some are concerned that climate action should not fall victim to this process. The European Commission, in particular, has argued that the two processes should be married and this is an opportunity to use ‘green’ funding as the primary fiscal stimulus, putting economies back to work on a new more sustainable basis.

In policy terms, it is about where funds get allocated. This could work to gas’ advantage or disadvantage. In Europe, electricity systems have been shown to work well with a much higher percentage of renewable energy over more sustained periods. As the decline in demand has hit fossil fuel generation hardest, it has demonstrated the resilience and practicality of higher levels of renewable penetration. Why go back?

If, as the EC argues, this is an opportunity to accelerate the energy transition, then gas will probably suffer from demand failing to bounce back to its former growth trajectory and from intensified competition from renewables.

But the real deciding factor will be the degree to which India and China pursue coal-to-gas switching and the broader gasification of their energy systems, for example in transport. With some certainty that the price of gas, whether pipeline or LNG, will remain low, it is an opportunity to accelerate the process, and one which will reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Faced with economic hardship, the opposite policy path would be to prioritise domestic coal over imported gas in an effort to keep the coal mines and heavy industry working. This year’s likely large drop in greenhouse gas emissions may provide space to allow the expansion of renewables to phase out coal over time with less of a transitional phase based largely on gas.

There are still many unknowns. Severe recession will put major strains on all economies and the policy responses are far from certain.

There is also growing mistrust of China and its handling of the initial virus outbreak. While the issue of Chinese-US trade relations appeared to have been put to bed at the beginning of the year, the White House is becoming increasingly strident in its criticism of China and there is a significant chance that Beijing will not be able to deliver on its side of the trade agreement reached in January.

|

Covid-19: Time to revisit old grievances? Low oil prices are not all bad: they can also create a number of opportunities that deserve consideration by prospective investors. These include mergers and acquisitions; and the chance to demand fairer terms from host governments, the co-director of US upstream advisory firm Moyes & Co, Christopher Moyes, told a webinar hosted by law firm Volterra Fietta April 30. He said they were now in a stronger position to argue for improved cost recovery mechanisms or progressive profit-sharing; and for local content laws to be adjusted in favour of the foreign company. Investors could also press for the rights to the gas produced and for the local supply obligations to be redefined, if that had been problematic in the past. Other desirable changes the host government could make might include allowing a company that is entering bankruptcy to retain the licence while restructuring; and also allowing a company to assign licences freely without unreasonable state interference, refusal or delay. They could also press for functional regulation. There could also be some “once in a lifetime” chances to buy upstream assets where first oil and gas is a few years away, he said. The oil and gas can be sold forward, and prices are higher a few years out, he said. Countries cannot afford to play the game for long and need oil to be at $40/barrel to balance their books, so it is a question of time, he said. And lenders should not extend any relief or talk about debt forgiveness at this time, he said: governments that had chosen to keep their economies dependent on natural resources should learn their lesson and diversify. Volterra Fietta partner Agnieszka Ason said that while buyers might be unlikely to succeed in their force majeure claims – none had in the past and sellers are unlikely to set a precedent, at least in public – the number of major sales and purchase agreements expiring over the next few years in Japan and Korea does at least give them the chance to press for freer trade. Restrictive destination clauses imposed by sellers – already outlawed in the European Union, and opposed by the Japanese economics ministry – oil indexation pricing clauses and annual offtake clauses could all be challenged at renewal time, she said. Rights to divert cargos might also be loosened in the buyer’s favour. “The crisis will put volume and destination flexibility under the spotlight,” she said. But she warned that oil indexation did not necessarily work to the advantage of the seller. And she pointed out that with no gas trading hub in Asia, there is no local alternative to oil, barring spot assessments for delivery into northeast Asia. Experience has shown that spot gas prices at times of high demand – particularly during the aftermath of nuclear disasters or at the end of long, cold winters – can be very high relative to those priced against oil. However, at time of writing, neither of those possibilities seem likely. William Powell |