Oil & Gas in the Energy transition [NGW Magazine]

The energy transition is an integral part of the strategy to reduce carbon emissions and keep the average global temperature rise to below 2 °C by the year 2100, in line with the provisions of the Paris 2015 agreement – but this has hardly begun.

Despite all the efforts made to date, hydrocarbons, which constituted 81% of global energy demand in 2000, still provided close to 81% in 2018, but of a bigger total. And renewables provided only 4% of global primary energy consumption in 2018 – despite rapid growth during the last 20 years.

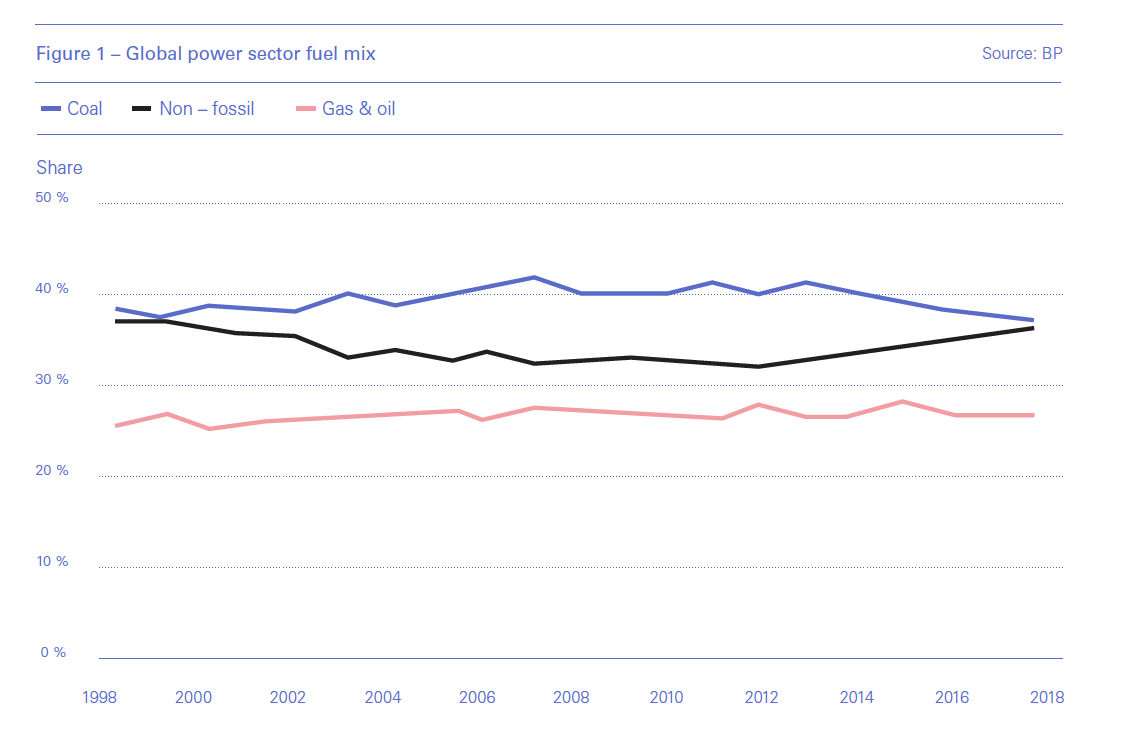

Even in the power sector, where renewable penetration is stronger, the fuel mix in global power generation remains flat, with the share of gas and oil in 2018 at 26%, and coal at 38% – unchanged from 20 years ago (Figure 1).

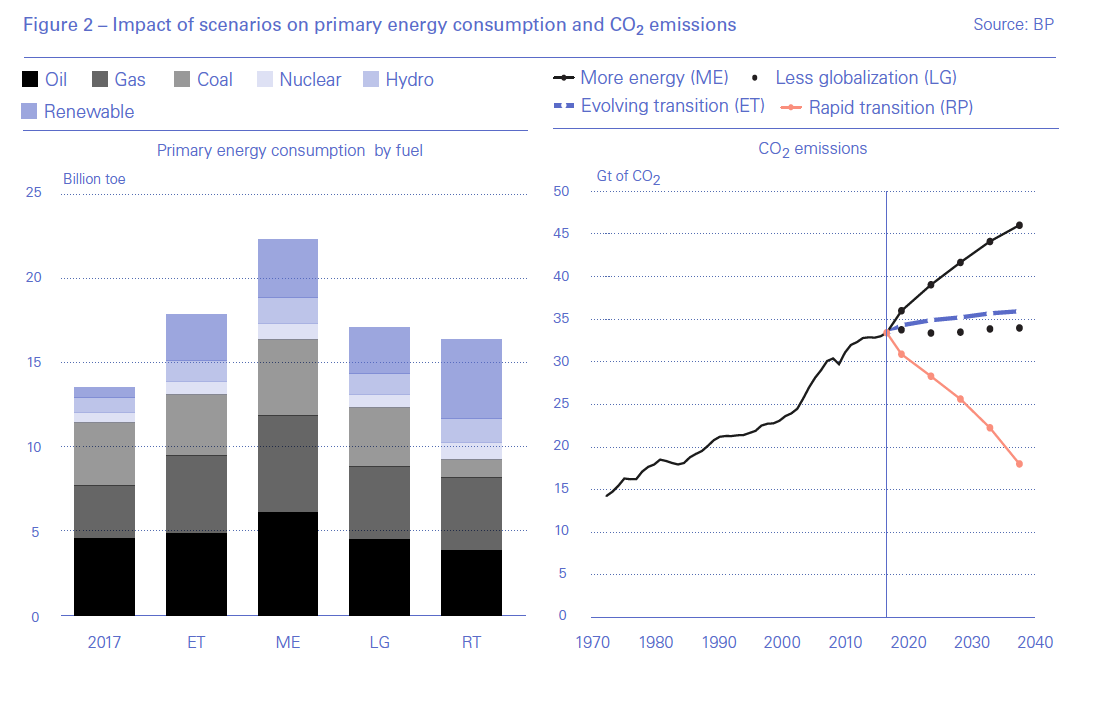

Evidently oil and gas has a role to play in energy transition. This is also clear from this year’s BP Energy Outlook 2019 (Figure 2).

In all the scenarios considered by BP, oil and gas provide a major part of the global energy mix to 2040. Even under the ‘Rapid Transition’ scenario, designed to meet Paris Agreement goals, oil and gas still meet half of global primary energy demand by 2040.

However, despite the fact that data show that there is a role for oil and gas well into the future - at least for the next 20 to 30 years - the social contract under which producers operate is changing. The energy transition is gaining momentum, with public support for cleaner energy strengthening. But the energy transition is also facing challenges as talk is cheap.

Challenges

Most countries are failing on their nationally determined contributions (NDC), declared when they signed the Paris climate change agreement. The UK’s Climate Change Committee, set up to hold government to account, said July 10 that the UK was likely to miss its targets, despite its net zero carbon pledge, and having sharply reduced its coal use for power this year.

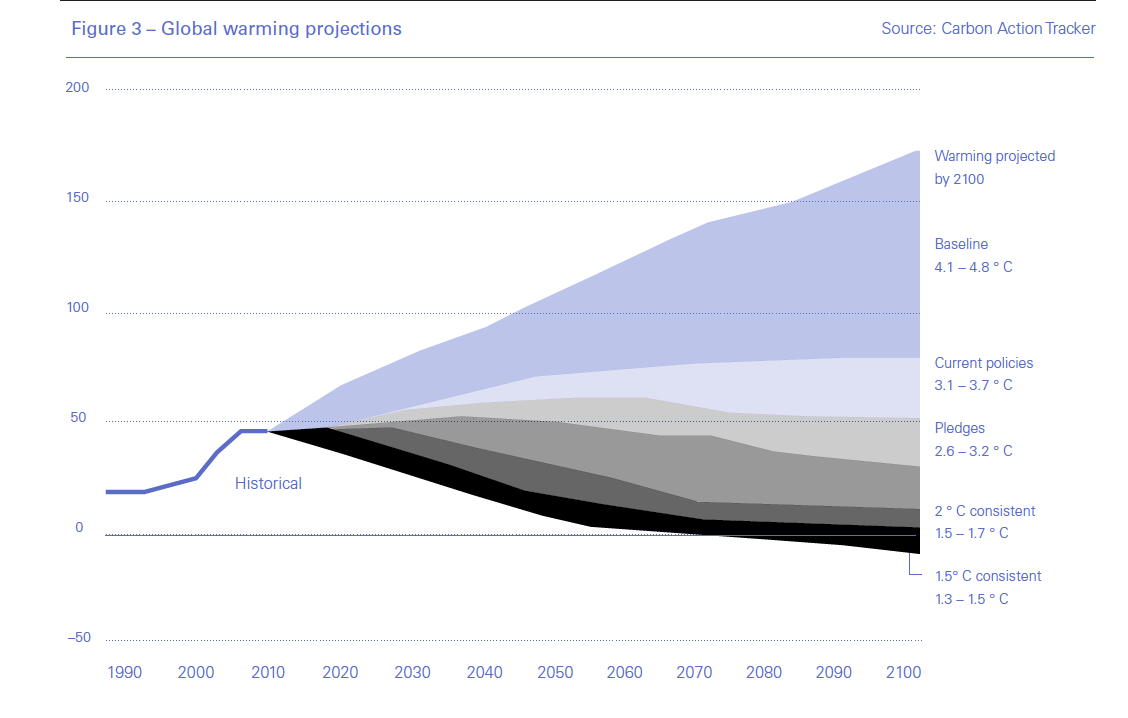

Current policies are expected to lead to a temperature rise of 3.1-3.7 °C (Figure 3), far above the 2 °C goal set by the Paris agreement, let alone the 1.5 °C maximum limit called for by the UN Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its Special Report published in October 2018.

Only 16 countries out of the 197 that have signed the Paris Agreement have defined targets in their national climate action plans ambitious enough to meet their NDC pledges. Worryingly, that list does not include the main polluters US, China and India and most European countries.

The IPCC is piling pressure on policy-makers, business and industry to take the required measures to achieve this change during the transition period to 2050. The IPCC report outlines a plan, based on a ‘manual of solutions’, of how to achieve its recommendations. The world must invest $2.4 trillion in clean energy every year from now to 2035 and reduce coal-fired power generation to more or less zero by 2050.

These are very challenging targets to meet, even without the need to ensure sufficient and affordable energy for all, free from disruption and unexpected consequences.

In the meanwhile, in Asia and Africa population growth and economic drivers mean that more affordable energy will be needed, to the extent that ‘cheaper beats cleaner’. Without change, coal demand in Asia is forecast to remain at 2012 levels even by 2040.

The fossil fuel industry is not making it easier. Technological improvements increase the competitiveness of shale oil and gas, for example, making it harder for renewables.

But oil and gas companies are also starting to embrace the need for change by investing in and planning for transition, often in response to pressure from their shareholders who are concerned about the longer-term security of their investments and demand more transparency and faster change.

Global energy demand

Despite the rapid increase in renewables, low-carbon energy is not keeping up with energy demand growth, which is expected by BP to increase by a third by 2040.

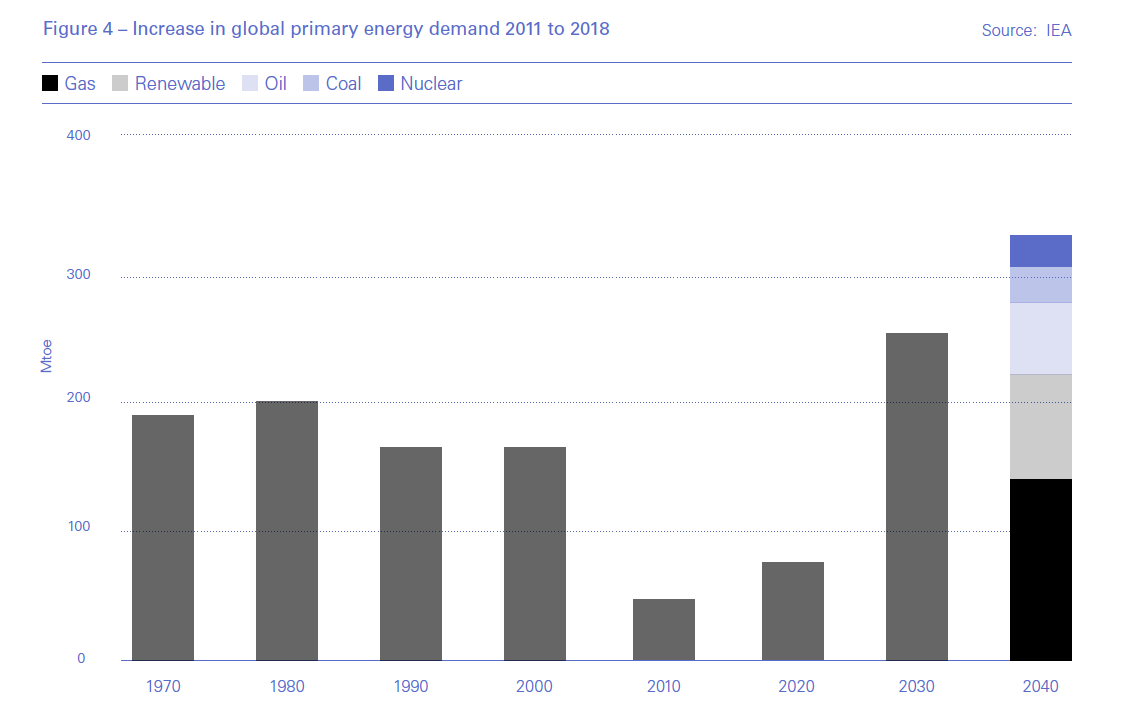

According to the International energy Agency (IEA), global primary energy demand increased by 2.3% in 2018, with carbon emissions going up 1.7%. Renewables provided only a quarter of this increase, gas 45%, oil 16%, coal 7% and nuclear 7% (Figure 4). Global electricity demand rose by 4%, with fossil fuels providing 55% of that, solar+wind only 26.5%, hydro 13% and others 5.5%.

In addition, the IEA says, after three years of decline, global energy investments stabilised in 2018 at $1.85 trillion. Of that, 42% were in oil and gas supply, 18% in renewables and 7% on coal.

Investment growth in renewables and energy efficiency slowed down in 2016 and 2017 and stalled in 2018. Also new renewable capacity added in 2018 was the same as in 2017, making it the first time since 2001 that annual new renewables installations failed to increase from the previous year.

The IEA states that an increase of 250% is needed in renewable and energy efficiency spending to deliver Paris goals. The IEA also warns that relative to 2015 when the Paris climate agreement was signed, “the appetite to push low carbon investments and policies is slowly fading.”

Energy investments now face unprecedented uncertainties, with shifts in markets, policies and technologies. Clearly the world is not investing enough in cleaner energy technologies to change course.

In the meanwhile spending on oil and gas in going up, making up for the mismatch in clean energy investment and future global energy needs – expected to increase by a third by 2040.

The outcome of all these developments is that output from low-carbon power investment is not keeping pace with demand. As a result, renewable growth is not keeping pace with increase in electricity and global primary energy demand.

But oil and gas companies will need to avoid relying on business as usual each year and paying lip-service to the need to change. Their social licence to operate is being challenged – increasingly the public is demanding faster change.

Research & Development

Another necessary step in the transition to cleaner energy is investment in research. Wind and solar is cheaper now but it still not able to compete for large scale supply of power without back up.

The energy transition also needs to combine low-cost, low-carbon solutions. China is already deploying large scale new grid technology. Europe should do the same by establishing a pan-European grid. Research should be a priority. That will position companies for the future.

But R&D spending is far short of what is needed. There is a need massive increase to develop new technologies required to combat climate change. Much of the responsibility lies with governments.

But responsibility also lies with oil and gas companies. So far investment in low-carbon energy is a minimal fraction of their annual spend. According to the IEA World Energy Investment report (WEI), out of the $1.85 trillion invested globally in energy in 2018, about $780bn was on oil and gas supply. Of that. just over $18bn was invested in R&D – all R&D, not just clean energy – well below 1% of global oil and gas revenues. The IEA says that this 45% below 2014 levels and “is not rising significantly as a share of revenue.” Clearly, if the oil and gas companies want to show that they are serious about energy transition, their R&D investment in low-carbon energy will need to increase substantially.

Role of oil and as companies

The outlook is for continued use of oil and gas well into the future:

- According to BP Energy Outlook 2019, oil demand is 100mn b/d now, and likely to plateau at 108mn b/d in the 2030s and declining slowly after that.

- Use of oil in vehicles is expected to be limited by electric vehicles. But it will take time. There are only 5.6mn EVs on the road now against 1.2bn internal combustion engine vehicles.

- There are no obvious substitutes yet for use of oil in land or seaborne freight or aircraft or petrochemicals.

- Gas use also rising worldwide, if not in Europe

The result is that emissions are still rising worldwide.

So, in that context what should be the role of oil and gas companies? First they need to manage and reduce emissions from their own activities, by tackling:

- Methane emissions

- Other waste losses

- The carbon footprint from their operations

- Fuel mix – replacing coal with gas where possible

- Efficiency of energy use – clean petrol, vehicle mileage per gallon, reduction of emissions per unit of energy consumed.

The oil and gas companies are beginning to do much of this. They are also starting to develop low carbon businesses. Each company will do different things, but all can use their global reach, skills and technology to experiment and establish knowledge of low carbon businesses.

Industry has also started doing some of this, but still very small – less than 5% of capex last year.

The problem is different rates of return from oil and gas investments in comparison to renewables. Oil-field development is all about access to resources and is producer-led and can produce IRR of 20%+. Wind farm returns are at most 8%. In addition, the low carbon part of the electricity sector is highly competitive with few barriers to entry.

The two sectors are very different. These contrasts make investment decisions challenging.

What is needed by the oil and gas companies is organisational change to create distinct entities – to create clean energy subsidiaries which are:

- Cross subsidised

- Sharing some skills and brand

- But separate balance sheet

- And separate investment criteria

The subsidiaries, such as Shell’s New Energies division, can then grow and one day take over.

Just as the energy market is in transition, so too are the organisational structures of the energy businesses. For the next two decades, as we move through the transition phase, there is no reason why both the old and the new cannot both thrive.

Climate change continues

The challenge for oil and gas companies is that climate change continues, with emissions likely to keep rising. The last two years saw energy demand and emissions going up and 2019 is going in the same direction.

Clearly the road to net-zero emissions by 2050 is extremely difficult, with no easy solutions, as the results so far show. There are serious challenges ahead – without measures to accelerate it, decarbonisation will be a slow process.

Governments need to act quickly to provide the required policy regimes to correct this situation and bring energy transition back on track. What is needed is strong policy and government leadership – globally.

But switching to clean energy sources while maintaining economic growth and providing energy on demand remains a challenge.

As BP’s CEO Bob Dudley, said continued investment in the oil and gas industry is essential to meeting the dual challenge of providing billions of people with more energy while drastically lowering carbon emissions.

The oil and gas companies see natural gas playing a major role in global energy for decades to come. Some of them do also invest in renewables, low-carbon energy and electric vehicle technology. But in response to the rapidly changing public opinion and perception of oil and gas as a major contributor to global warming, as a class they need to embrace change faster and be more transparent about their actions.

Challenges

Energy transition is dependent on going beyond the lifestyle choices evident in Europe. It needs to penetrate markets in Asia like India, which is experiencing rapid growth but is far from being rich. In Asia affordable energy is key.

But even Europe is finding it difficult. That is why Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic prevented a decision by the EU late June to adopt net-zero emission targets in 2050. Abandoning coal will have a high social and economic cost.

NGOs appear to have reached a limit of campaigning against governments. As a result, they are now refocusing on companies.

For the oil and gas sector the problem is not supply - there is plenty - or demand . The challenge is how to maintain trust as they continue to work in a business which is increasingly seen as doing damage.

An article prepared jointly by Charles Ellinas and Nick Butler based on presentations made at the Energy Transition Forum that took place in Vienna June 6-7, organised by IENE. Nick Butler is a visiting professor at King's College London and has held senior positions in BP’s strategy and policy department.