Nuclear first policy: implications for LNG in South Korea [Global Gas Perspectives]

In its 11th Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand, Seoul confirmed its return to nuclear expansion, putting in place a near complete reversal of the previous administration’s policies.

Under former president Moon Jae-in, no life extensions for existing reactors were allowed and all new build plans, bar the completion of the Saeul 3 and 4 reactors (formerly Shin Kori 5 and 6), were cancelled. Nuclear power was to be phased out. Under President Yoon Suk Yeol, who assumed office in May 2022, life extensions will be granted and new building plans have resumed.

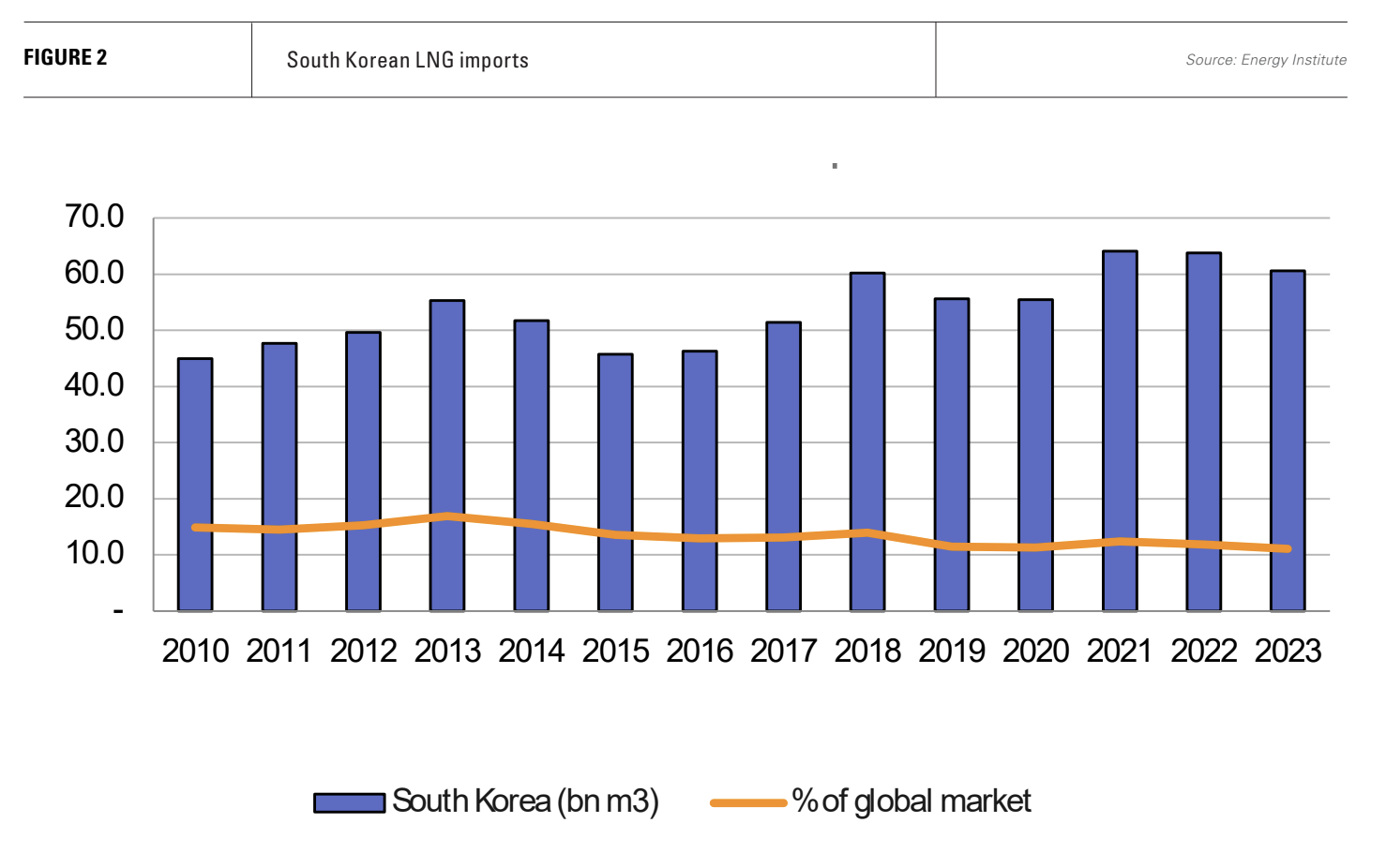

The re-commitment to nuclear power has obvious implications for the use of LNG, and for the trajectory of South Korea’s energy transition. The country is the third largest market for LNG after China and Japan, importing 60.6bn m3 of the fuel last year, equivalent to 11% of the global market.

Policy inconsistency

Given long construction times for reactors and the need to maintain a highly skilled workforce, nuclear power is usually developed with cross party support for the technology. South Korea’s policy inconsistency is therefore notable.

Public distrust of the nuclear industry in the country is substantial, following a series of scandals over the last decade and more, the issue of growing piles of nuclear waste with no long-term storage solution, and still resonant memories of Japan’s Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011.

At the same time, public opinion is also strongly in favour of developing a nuclear weapons arsenal to counter the threat posed by North Korea.

President Yoon does not have solid electoral backing. Legislative elections in April, essentially a mid-term referendum on the government’s performance, returned a majority in the National Assembly for the main opposition and its satellite parties, amid a record electoral turnout. The opposition increased its majority to 192 seats out of 300, while the governing party’s representation fell to 108 from 114, further hindering its ability to pass legislation.

The country’s political polarisation and ambivalent position towards nuclear technology means current plans could be suspended by future administrations, once again re-writing the future of the country’s LNG demand.

Renewables getting squeezed

Although it envisages a large expansion of renewable energy capacity, the proposed Basic Plan falls short on how it will be achieved. South Korea already lags its OECD counterparts in renewables. Although solar deployment has accelerated, it provided only 4.8% of the nation’s electricity in 2023. South Korea has little hydro power and limited onshore wind capacity, both of which accounted for just 0.6% of 2023 power generation. Overall, renewables accounted for just 9.1% of total generation last year.

Moreover, according to Dr Hyejeong Kim of South Korea’s Sustainable Development Research Centre, the Yoon administration’s focus on nuclear is putting the squeeze on renewables. He points to the suspension of new permits for renewable energy in Honam region until December 2031 and government plans to designate 205 electricity substations across Honam, Jeju, Gangwon and Gyeonbuk as controlled substations, which can restrict wind and solar generation at any time.

The measures are being introduced to address grid congestion. As the government also intends to extend the life of the Hanbit 1 and 2 reactors in Honam, Kim suggests that blocking the connection of renewable energy projects and suspending new permits may be designed to secure transmission capacity for the nuclear reactors.

Grid limitations and complex permitting processes are already significant barriers to the expansion of renewables in South Korea.

However, the government is moving ahead, albeit slowly, with offshore wind. The first of a series of tenders is to be held this month with the aim of tendering 7-8 GW of offshore wind capacity between now and the first half of 2026. South Korea currently has just 136 MW of offshore wind, despite a target of installing 14.3 GW by 2030.

This target is unlikely to be met, given the low starting point and length of time it takes to build offshore wind projects, particularly in new markets. There is a lack of suitable vessels both in the APAC region and internationally for the large turbines most economical to install.

Fossil fuels – decline or stability?

Given South Korea’s flip-flopping nuclear policy and slow development of renewables, it is no surprise that neither coal nor LNG use have declined substantially in the last decade. Coal for power generation in 2023 was about 80% of its 2017 peak, but still contributed a third of the country’s power. At just over 200 TWh, coal, not LNG, remains the largest source of electricity generation.

Gas for power, all of which is sourced as LNG, generated 167 TWh, a reduction from a peak of 178.7 TWh in 2021 and 174.4 TWh in 2022.

The fall in fossil fuel use over the last two years was primarily the result of a jump in nuclear generation, owing to the connection to the grid of the 1.4 GW Shin Hanul-1 reactor in June 2022.

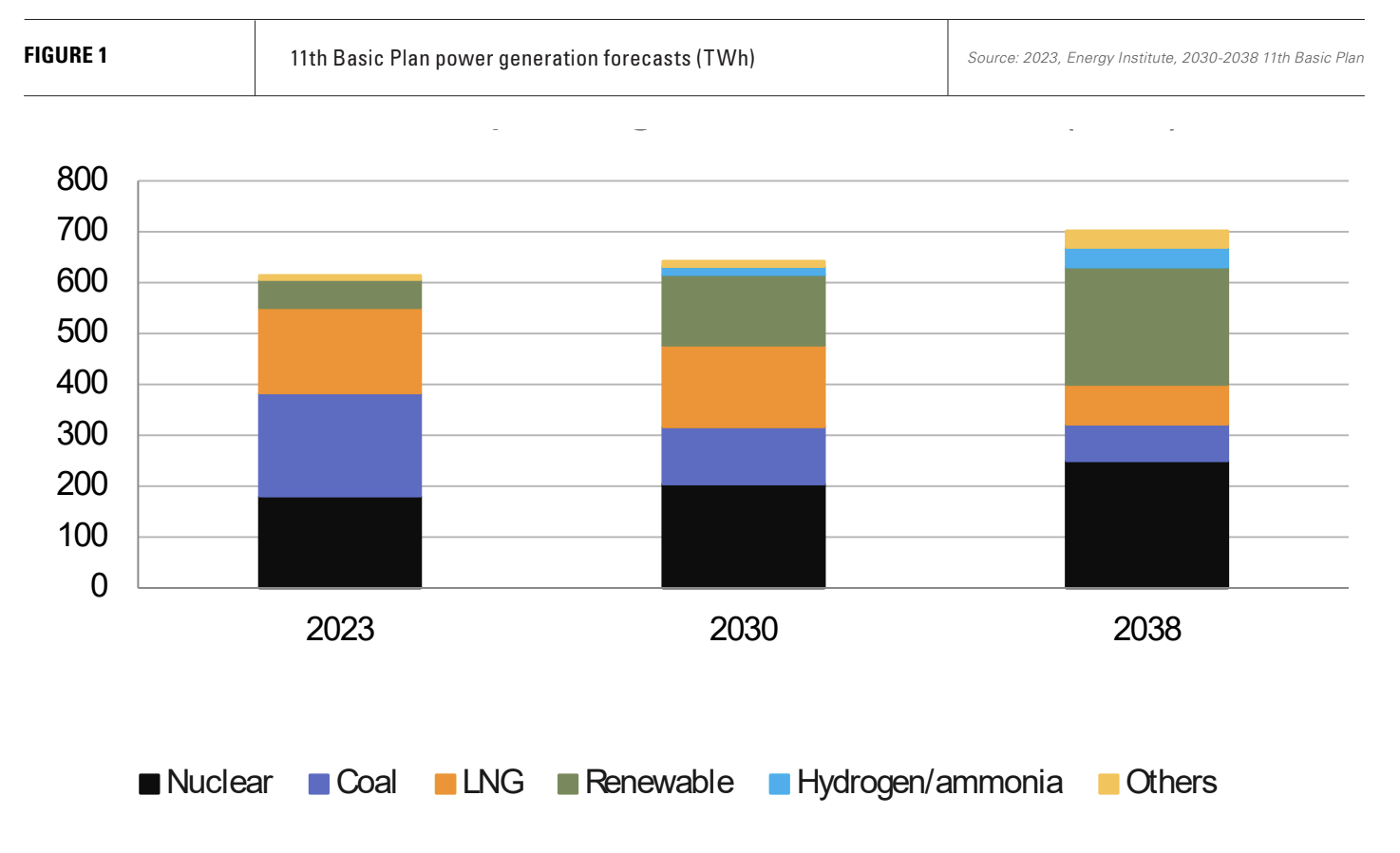

Over the medium-term, under the 11th Basic Plan, gas-for-power generation is forecast as fairly stable, even if its proportion of the energy mix falls. In 2030, LNG is expected to generate 160.8 TWh, not much less than in 2023, while coal generation falls substantially to 111.9 TWh.

The reduction in coal use of 90 TWh and about 30 TWh of demand growth is made up primarily by a large jump in renewable energy output (83 TWh) and a more modest increase in nuclear generation (24 TWh), reflecting the start of operations of Shin Hanul-2 at the end of 2023. The plan also incorporates a somewhat speculative contribution from hydrogen/ammonia of 15.5 TWh.

Renewables generated 55.7 TWh in 2023 and need to rise to 138.4 TWh by 2030. This looks ambitious given the lack of onshore wind and hydro. It depends on the continued acceleration of solar, which has a low capacity factor, meaning a lot more capacity needs to be built to achieve the required output, just as the government is slowing down permitting for grid congestion reasons.

The government’s renewables target thus appears to bank on the successful development of offshore wind. If the proposed tenders are successful between now and mid-2026, this would probably only mean 7-8 GW at most in operation by 2030. Even that is an unlikely permitting and construction timeline. If installed, this would generate only about 25-28 TWh.

Post 2030, LNG use is forecast to fall sharply

The 2030-2038 period looks very different. Gas for power use falls sharply, more than halving to 78.1 TWh in 2038. Coal use also falls but less than LNG in this period, dropping from 111.9 TWh to 72.0 TWh. Notably, the government has not set a date for the complete phase out of coal and has rolled back plans for the conversion of coal-fired power plants to LNG. As a result, both coal and LNG maintain reduced but roughly equal shares of the generation mix in 2038.

Given that all the necessary infrastructure to sustain higher LNG imports is in place, the lack of coal-to-gas switching appears a lost opportunity to wean the country off coal in a much shorter time period.

The loss of generation from coal and LNG, plus forecast demand growth, in the period 2030-2038 amounts to 183 TWh. This will be met by the construction of three new nuclear plants and the country’s first Small Modular Reactor (SMR). SMRs are an experimental technology which has yet to be proven. Nuclear generation would provide an additional 45 TWh on top of 2030 levels, according to the plan.

The remainder would come from the further expansion of renewable power (plus 92.4 TWh between 2030 and 2038) and a further 23 TWh from hydrogen/ammonia, which, to be carbon free, would mean more renewable energy capacity combined with electrolysis.

LNG demand collapse scenario

In June, the government announced the identification of oil and gas prospects off the country’s east coast, which it says could hold as much as 14bn barrels of oil and gas. Yoon has authorised the drilling of five wells in an effort to firm up the prospects’ potential.

Domestic oil and gas production, which is currently negligible, would allow the country to reduce its dependence on imported energy fossil fuels in a period of rapid demand decline. As a result, a combination of success in implementing the 11th Basic Plan and domestic gas production could potentially see a collapse in the country’s LNG demand in the 2030-2038 period.

The development would be justified on energy security grounds, but would also be likely to lock oil and gas use into the country’s energy system long term. Eliminating a domestic industry is much harder than eliminating imports.

As a result, it is hard to form even a most-likely scenario for South Korea’s LNG demand trajectory. In addition to the uncertainties governing renewables, nuclear and the possibility of domestic gas, the Basic Plan may overestimate electricity demand growth, which is expected to come primarily from the growth of AI and related technologies.

However, it does appear that unless much greater efforts are made to address grid limitations, South Korea will continue to lag its OECD counterparts in terms of renewables, sustaining, in the absence of domestic gas production, its dependence on both LNG and coal.