[NGW Magazine] China reforms state owned enterprises

China’s mixed ownership and structural reforms is racing along with concrete steps taken in natural gas, oil, power grids, amongst other heavy-weight industries such as military, aviation and rail.

China’s structural reforms of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) is proceeding, affecting natural gas, oil and power grid operators. Other heavy-weight industries such as defence, aviation and the railways are also a part of the plan.

The reforms have achieved much in just one year. The hype surrounding SOE reform funding and the idea of sophisticated models and distribution of financing could eventually filter down to aiding mid-sized companies in collaboration with SOEs.

They are also likely to speed up China’s energy mix diversification – especially the clean energy drive towards conversion from coal to gas – and to reduce debt in the economy. Regulating debt allocation is one way to ensure efficient return on capital.

It could also indicate how China’s economy is moving towards a free-market economy, where responsibility for planning is devolved to corporate managers in a co-ordinated manner.

Mixed-ownership reform is the first step towards overall SOE reform, according to China’s State Council in a statement issued late last year. China has an estimated 150,000 SOEs, holding more than 100 trillion yuan in assets and employing more than 30mn.

With the first fund, the Structural Adjustment Fund (SAF), set up in September 2016, market-oriented reforms by state-owned asset investment companies are designed to make the Chinese state a “stakeholder” instead of an enterprise manager, introducing private capital and lowering the financing costs of some industries.

Promoted by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (Sasac) and the two state-owned asset management companies, China Reform Holdings and China Chengtong Holdings, three main strategies are in progress.

First, a yuan 200bn state venture capital fund has been established; and Chengtong Holdings set up the yuan 350bn SAF. China’s largest private-equity fund with an initial capital of yuan 131bn, its key capital sponsors include China Petrochemical Corporation (Sinopec), China North Industries Group Corporation, Shenhua Group, Postal Savings Bank, China Merchants Group and Beijing Financial Street Investment Group.

The funds, especially Chengtong, will pool private, state-owned and eventually overseas funds for the overall project of structural reforms within the SOEs.

The larger-capitalised SOEs will also facilitate alliances, divestments and mergers involving first the steel industry; then other industries – possibly, petrochemical, gas, coal and other emerging strategic industries – will follow. The funds will also finance supply-side structural reforms through SOE upgrades and industrial consolidation.

The steel sector is first up for the surgery, as it has to address its over-capacity and exit inefficient assets, overseen by the Chengtong-initiated SAF. It is also in the plan that the gas pipelines, oil, marine equipment and power grids undergo reorganisation, although no timeline has been set. Overlapping businesses may be merged, as the gas grid expands when coal is replaced. Cutting carbon emissions from power grids could be another uphill task in the future.

SOE Strategises To Reduce Debt

Second, the two SOE reform funds will have official equity shareholding in the listed companies, even though these stakes may not yet have significant control rights.

According to Sasac, at the end of 2016 SOEs had stakes in 290 A-share listed companies on the Shanghai Mainboard Stock Exchange whose operating income and profits account for 39.3% and 30.07% of total A-stock market share respectively. Foreign investors have only limited access to A-shares, denominated in local currency, while B shares are denominated in dollars.

Most recent cases include China Reform and China Chengtong increasing stakes in publicly-listed China Merchants Bank, Baoshan Iron & Steel and Wuhan Iron and Steel.

The debt-for-equity swap announcement with China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation has a market-leading effect since the SOE-mixed ownership reforms started more than a year ago. CSIC has several oil, gas and construction companies under its control.

For the past two years of declining demand, CSIC and its companies have suffered as customers have walked away from half-complete or even complete oil and gas construction projects, losing minimal deposits sometimes worth just 1% of the total value, leaving the contractor out of pocket. These projects include gas platforms, pipelines, transport and other infrastructure.

Such significant rescue moves are aimed at optimising the target companies’ debt ratios and strengthening the influence of the SOE reform agents: Chengtong and China Reform.

As its third strategy, China Chengtong said it will hold equity of selected SOEs to tackle problems during business reorganisation and revival. The ultimate aim is to complete the modernisation, upgrading business capabilities and reallocate resources. An estimated 69 companies are scheduled to complete restructuring by the end of 2017, according to Sasac.

In October, Sinochem’s potential initial public offering (IPO) was associated with the mixed ownership initiative. The IPO of China’s fourth-largest energy company is planned for the second half of 2018.

Well-placed sources were quoted in mainstream media saying the listing excludes under-performing overseas oil and gas production assets, whose value were impacted by the oil price slump. Sinochem will focus on its traditional value-added refining, fuel retail and storage businesses. Its strategy follows the direction taken by some of the other SOE structural reforms.

While the two state reform funds are said to be initially focusing on the steel industry, there are no obstacles to the funds increasing their shareholdings in a company such as Sinochem. In fact, this move is likely to add momentum and credibility to the reform initiative, and representing the state simply as an investor-stakeholder, as opposed to a direct stakeholder who is there to manage.

One Belt and Road

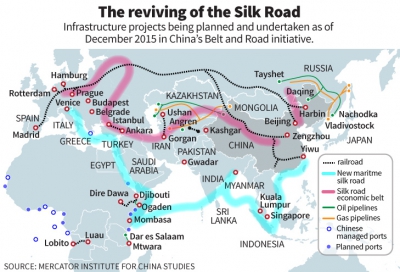

Chengtong is also preparing to set up several sub-funds, one of which to support and invest in overseas operations of Chinese SOEs under the One Belt and One Road initiative, according to Chengtong Holdings chairman Ma Zhengwu.

A certain percentage of the Belt and Road Initiative is for infrastructure servicing the gas and petrochemicals industry. Potential overseas partners already in talks include Russia regarding a pulp and mill project, and there is potential for other projects.

The China Bond Market 2016 report by the Climate Bonds Initiative and the China Central Depository & Clearing Company also stated that the China’s Belt and Road Initiative creates other investment opportunities for infrastructure projects with possible implications for green bonds both onshore and offshore China.

Private transport provider China LNG told the stock exchange in October that it is in talks with a state-owned enterprise energy company regarding a joint issue of a yuan 5bn bond for three LNG infrastructure projects in Fuping, Huanggang and Jiangyin.

Although the identity of the SOE has not been confirmed, Chengdu Huaqi Houpu Holding and China Nuclear Industry Fifth Construction in November entered into an initial agreement with China LNG for an industrial investment fund for clean energy.

These projects are planned for completion in the next three to five years, with projected revenues in the millions. Amongst these projects include coal-to-gas and clean energy asset transformation plans.

Regarded as “emerging industries” in this recent context, clean energy projects are yet to be considered a priority for China’s reform funds. However it is an area that funds are likely to favor in the near future, especially if it is believed to improve the capital structure of companies such as China LNG.

Green bonds are a potential legitimate tool for the China reform agents – China Chengxin Holdings and China Reform Holdings – to increase their ownership in key state-owned enterprises in strategic industries.

sCarbon-intensive industries will benefit from financial instruments set up to reduce the carbon footprint and increase the energy efficiency of companies and sectors.

Green bonds can change the debt quality and provide a way out for financially distressed companies while ensuring green investments are part of the companies’ future development.

This strategy would be strengthened by investment-grade and internationally recognized Chinese green bonds issuance, enhanced by a growing green financial system mentioned in China’s 13th Five Year Plan.

According to a China Bond Market 2016 report compiled by the Climate Bonds Initiative and the China Central Depository & Clearing Company (CCDC), domestic green bond issuance increased in 2016 from zero to US$36.2 billion, accounting for 39% of global issuance in 2016.

Global growth in green bond issuance was driven by China 2016

Source: “China Green Bonds Market 2016” Prepared jointly by the Climate Bonds Initiative and the CCDC. Accessed online in August 2017.

Green bonds is also part of China’s coal-to-gas transformation, as such investments by public and private Chinese companies are contributing to the greening of municipalities and provinces in the next five to ten years.

Half of China’s green bonds last that long, according to the CCDC. Bond proceeds are spent in a range of projects, such as clean energy, clean transport, pollution prevention & control, resource conservation and recycling and energy saving.

Variants of green bonds are in the process. These include green credit, green financial bonds, green corporate bonds, green enterprise bonds, green asset-backed securities and green development sub-funds. These could be made accessible via the two state-owned asset management companies.

Staff