Scenarios and Outlooks for Energy

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 18

By Charles Ellinas

The non-energy company DNV GL has thrown its hat into the ring with a forecast of energy supply and demand during the transition to a lower carbon global economy. NGW looks at how it compares with other companies' and agencies' outlooks for energy

DNV GL released its first Energy Transition Outlook on 4 September, presenting the results of its study into a global and regional energy transition to 2050.

Among quite a few such outlooks published this year, this one claims to be different in that – as a provider of third party and technical advisory services both to the fossil and renewables industries – the classifier and registrar DNV GL takes an independent and balanced view, with the novelty of anchoring its case to a ‘central’ base rather than offering a range of outcomes depending on which ‘scenario’ the reader thought likeliest.

DNV GL designed a model of the world’s energy system independently, depicting globally interconnected demand and supply of energy, within ten global regions, and the transport of energy between those regions, and based its work on this. It incorporates the entire global energy system from source to end-use.

This is what makes this an important outlook to analyse and draw from its findings and conclusions.

In his introduction, DNV GL CEO Remi Eriksen says: “We forecast that by mid-century, primary energy supply will be split roughly equally between fossil and renewable sources. That presupposes a very substantial growth path for renewable energy, but not enough, we calculate, to bring humanity on track to reduce climate emissions in line with the climate goal agreed in Paris in 2015.” How does this compare with forecasts in other organisations’ Outlooks, such as BP, Shell, International Energy Agency (IEA) and Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF)? And what are the key differences if any?

But the good news is that during this period of transition DNV GL’s forecast demonstrates the key role that the cleanest fossil fuel, gas, has to play: it remains the biggest energy source even in 2050.

Key findings

DNV states that on a global scale, the energy transition will be dramatic, but it will be experienced unevenly across the world’s regions.

The key findings are:

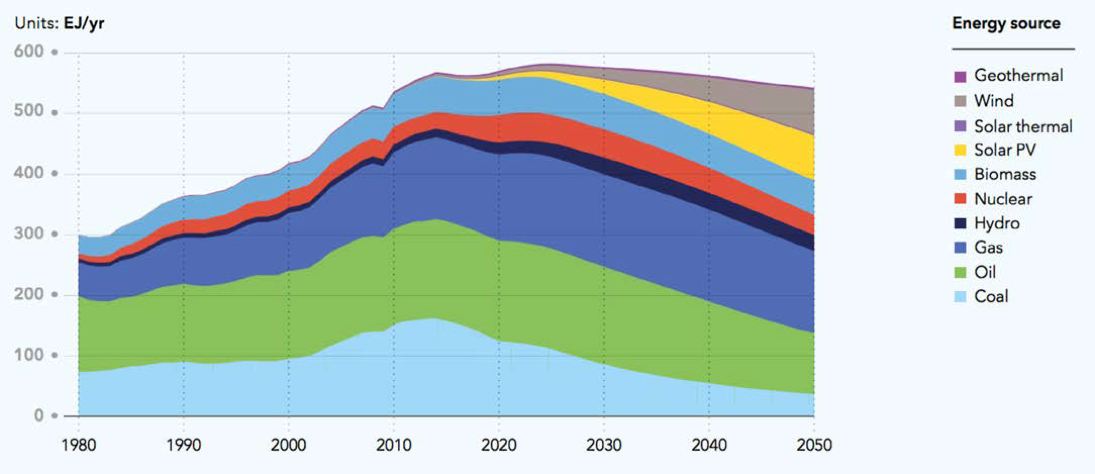

- Energy efficiency will improve faster than global economic growth due to the rapid electrification of the world’s energy system, leading to a peak in primary energy demand during the mid-2020s (Figure 1).

- Renewable energy sources will continue to rise, making up nearly half of global energy supply by 2050, halving energy-related CO2 emissions by that time.

- Gas supply will peak in 2035, but will still be the biggest single source of energy by mid-century.

- Oil supply will flatten out in the period 2020 to 2028 and then fall significantly to be surpassed by gas in 2034.

- The world will manage the shift to a renewable future without increasing overall annual energy expenditure, meaning that the future energy system will require a smaller share of GDP.

- Despite greater efficiency and reduced reliance on fossil fuels, the Energy Transition Outlook indicates that the planet is set to warm by 2.5˚C, failing to achieve the 2015 Paris Agreement target.

A rapid decarbonisation of the energy supply is underway with renewables set to make up almost half of the energy mix by 2050, although gas will become the biggest single source of energy, but prices will stay low.

Global energy demand

The world is experiencing a rapid energy transition, driven by electrification, boosted by a strong growth of wind and solar power generation, and further decarbonisation of the energy system, including the decline in coal, oil, and gas, in that order.

DNV GL forecasts that global primary energy supply will peak by 2030s and stay largely unchanged to 2050 even in the context of continued population and economic growth. This is at variance with most other energy outlooks which forecast continued increase in primary energy demand – for example UK BP, the International Energy Agency and Shell – even if at a slower pace.

This is due to increased energy efficiency on a global scale, driven by the growing share of electricity in the energy mix, with energy losses reduced through the steady uptake of efficient renewable sources.

This is due to increased energy efficiency on a global scale, driven by the growing share of electricity in the energy mix, with energy losses reduced through the steady uptake of efficient renewable sources.

DNV GL says that coal use has already peaked, oil will peak within the next 10 years – which could easily reverse if a giant like China burned a few percentage points more coal – and gas in 20 years, but gas will remain the biggest single source of energy for the world through to 2050. BNEF shares this view. It expects the world’s hunger for coal to abate starting around 2026 as governments work to reduce emissions in step with promises under the Paris Agreement on climate change. But this assumption faces challenges, considered later in this article.

Today, the world’s energy is used in transport (27%), buildings (30%) and manufacturing (31%). By 2050 these will change to 23%, 33% and 32% respectively. Transport declines as vehicle electrification materialises.

From the perspective of where the energy is sourced, according to DNV GL the demand picture is more dramatic. Although total energy demand is almost flat, there are big changes in its composition. In 2015, electricity represented 18% of the world’s final energy demand but by 2050, its share will become 40%. Electricity replaces both coal and oil in the final energy demand mix, and the trend of electrification is strong in all regions.

Renewables

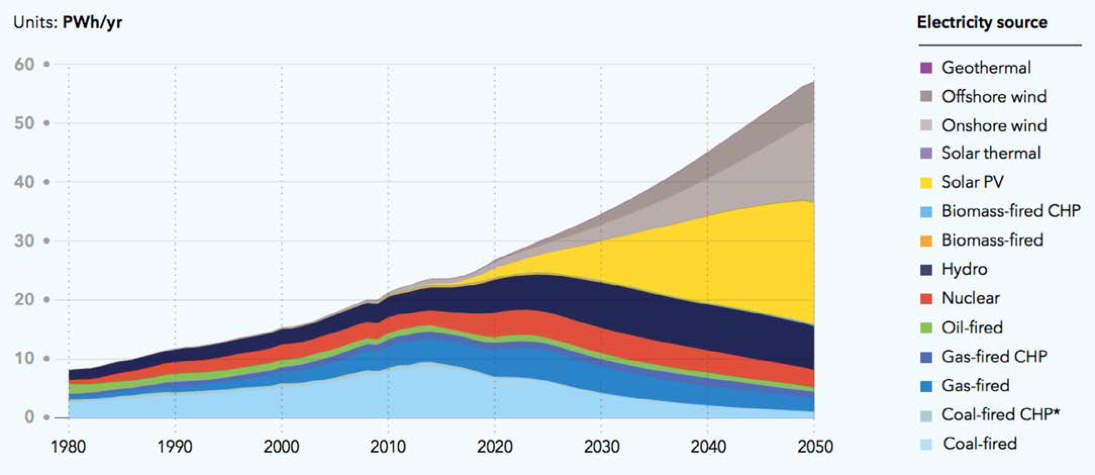

Renewable energy – chiefly wind and solar photovoltaic cells (PV) – holds the most potential for cost-competitiveness. Solar and wind will rapidly become cheaper than fossil fuels, despite the low cost of the latter. As a result, renewables will expand to make up 44% of primary energy supply and 85% of electricity supply by 2050. At the same time the share of electricity in total energy supply will rise dramatically from 18% today to 40% in 2050.

Renewables will increasingly dominate world electricity generation, with solar PV and wind each having a 36% share. Two-thirds of wind power will come from onshore by 2050. For both wind and PV, forecast growth depends strongly on continuing cost-reduction trends. This implies further technology developments. BNEF estimates that by 2030, unsubsidised new solar and onshore wind will undercut existing coal and gas generation. If that happens it will be a tipping point for electricity production.

Electricity supply will be dominated by variable renewables (Figure 2). But DNV GL believes that this will not cause insurmountable problems for grid balancing in order to maintain secure electricity systems. Such major penetration is beginning to take place in various European grids, and the system operators have shown themselves capable of addressing problems. As penetration increases further, so will innovation.

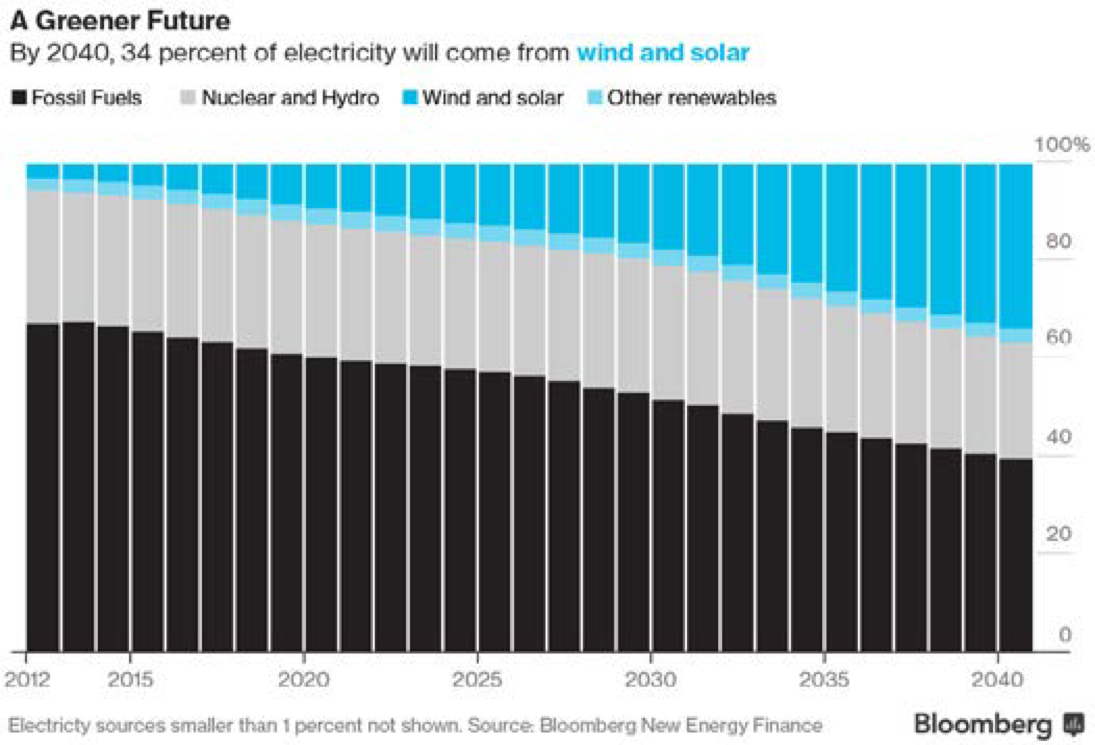

This is a more bullish view in comparison to most other forecasts. Even BNEF does not expect renewables to dominate electricity production (Figure 3). It expects renewables, solar and wind to provide about 34% of global electricity production by 2040, with fossil fuels still providing about 40%. According to DNV GL the contribution from fossil fuels will be only about 15% over the same period.

According to DNV GL electricity production from nuclear and natural gas changes only slowly over the forecasting period, indicating that robust industries are likely to continue, even after some consolidation.

Interestingly, it goes on to say that when heat must be decarbonised, the current fossil-fuel options for heating will be unavailable, impacting costs. Governments may therefore have to justify heat supply becoming significantly more expensive. This would be a big challenge.

Energy efficiency

DNV GL’s outlook shows that the world’s energy system is highly sensitive to changes in energy efficiency. The IEA states that half of global emission reductions can be achieved through energy efficiency measures – a view shared by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The world’s energy intensity – the amount of energy per unit of GDP – has been declining on average by 1.4% per year for the last twenty years. According to DNV GL, the electrification of the global energy system would cause this to almost double to an average annual 2.5% decline per year.

Electricity use, especially derived from solar and wind energy, is much more efficient with less heat losses than is the case for fossil fuels. But is this achievable? What are the challenges?

The European Commission has put the EU at forefront of delivering energy efficiency improvements. It has even adopted the principle of “Efficiency First”, setting a target to deliver energy savings of 30% by 2030. However, at an Energy Council meeting on June 26, the EU energy ministers adopted proposals that appear to water down energy efficiency. It has been estimated that, unless rectified, proposal loopholes could reduce the current EU energy efficiency target from 1.5%/yr to less than half of that and in a worst-case scenario down to almost zero.

This is indicative of the challenges being faced. If the EU, which is at the forefront of combating climate change, is finding it difficult to increase its ambition, what would the challenges be in less committed countries?

Oil and gas

DNV GL forecasts that renewables and fossil fuels will have an almost equal share of the energy mix by 2050. Wind power and PV will drive the continued expansion of renewable energy, while gas is on course to surpass oil in 2034 as the single biggest energy source.

Oil is losing ground as a source of heat and power, and demand is set to flatten from 2020 through to 2028 and fall significantly from that point as the penetration of electric vehicles gains momentum. This is not very different from what Shell and Statoil have said they expect to happen, but it is considerably earlier than estimates by BP and the IEA. Even the International Monetary Fund is now predicting the end of the oil age, stating that it is not whether but when.

Given the long lives of many oil projects, even the possibility that world demand could be peaking in the 2020s and will start falling after that is something that could affect future investment decisions, such as BP’s September 14 extension of the Azeri production-sharing Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli oil and gas agreement to 2049, from its normal expiration of 2024

A contributor to the oil demand peak is a very rapid shift to electric vehicles (EVs). This is driven by an increasing number of countries, including the UK and France, committing to ban fossil fuel vehicles by 2040. China is also considering an eventual ban.

However, as BP’s Spencer Dale points out, the global car fleet accounts only for about 20% of the world’s current oil consumption. So even if the EV uptake by 2050 reaches 50%, the impact of this on oil demand will be limited.

According to DNV GL the fossil fuel share of the world’s primary energy mix will decline from 81% now to 52% in 2050, of which the share of oil and gas will be 44%.

Even so, fossil fuels will still comprise about half of the total energy supply by 2050. Oil and coal now provide 53% of the world’s global energy supply. By 2019, coal will be overtaken by gas, and by 2034, gas will surpass oil to become the largest energy source. However, BP (Figure 5) and the IEA forecast gas overtaking coal in the 2030s and not overtaking oil during the reference period. The US Energy Information Administration also agrees with this.

This means that oil and gas will retain an important role in the global energy mix even by 2050, requiring continued investment in new projects to maintain production capacity. The possibility of peak oil demand is one of the factors driving the oil companies to increase investments in gas.

Gas will continue to play a key role alongside renewables in helping to meet future energy requirements. Its contribution to total global primary energy will decline from 27% at its peak in 2034 to 25% by 2050, but it will still be the dominant fuel source.

Major oil companies are already increasing the share of gas in their reserves to meet this future demand, especially LNG. The industry is betting on gas overtaking coal thanks to its clean characteristics relative to both oil and coal. The gamble on gas rests in large part on the expectation that it will squeeze coal out of the global energy system and compete with the rise of wind and solar power.

Maarten Wetselaar, head of Shell’s gas business is “absolutely convinced that gas will provide that role.” But natural gas needs to remain affordable and possibly at prices even lower than now. An abundance of resources and a near flat demand are likely to keep prices low.

ExxonMobil’s mid-September cave-in to LNG pricing demands from India is indicative of the challenges. Buyers are already gaining the upper hand, aided by ample gas and LNG supplies. It is a trend producers need to learn to live with, requiring further reductions in production costs. Higher cost projects will be fraught with risks.

DNV GL concludes that in an energy future with more intensive competition and reduced oil demand, the oil and gas industry will intensify its focus on cost efficiency to remain competitive over the forecast period.

Assumptions and challenges

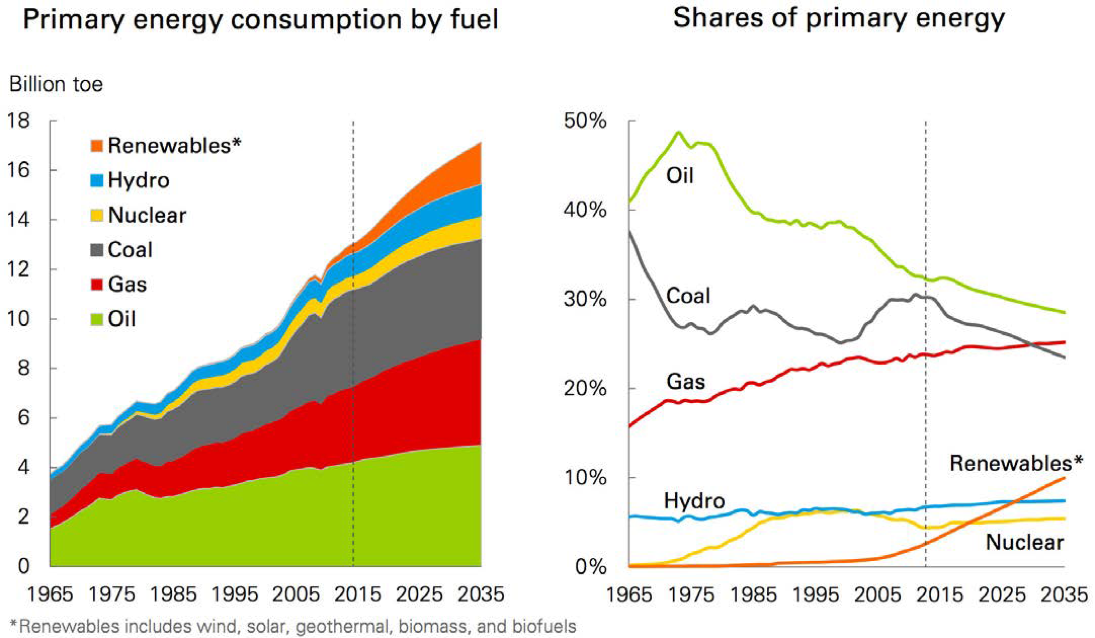

The big assumption in DNV GL’s work is that coal will decline dramatically from providing about 26% of global primary energy now down to only 8% by 2050. This is in contrast with BP’s Energy Outlook 2017 forecast (Figure 4).

It is interesting to compare the two. The total primary energy consumption by 2035 according to DNV GL will be about 20% than estimated by BP. DNV GL forecasts that global primary energy consumption will peak in the 2030s and stay flat after that, while in BP’s Outlook it continues growing, albeit at a lower rate.

It is interesting to compare the two. The total primary energy consumption by 2035 according to DNV GL will be about 20% than estimated by BP. DNV GL forecasts that global primary energy consumption will peak in the 2030s and stay flat after that, while in BP’s Outlook it continues growing, albeit at a lower rate.

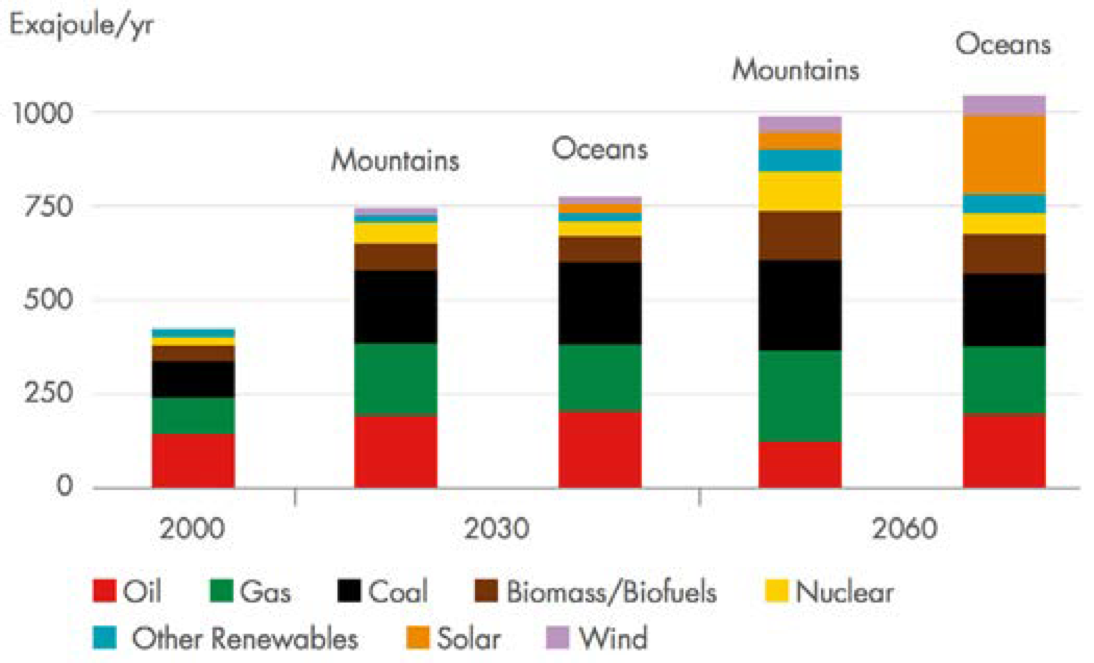

The more recently released Shell’s Scenarios Energy Models appears to agree with BP (Figure 5). And so does EIA which forecasts a 28% growth in global energy demand between now and 2040, with almost all growth coming from of non-OECD countries.

Shell’s ‘mountains’ scenario explores the widespread success of shale gas and strong government policy to reduce oil use in transport and use of so-far trivial amounts of carbon capture and storage to reduce emissions; ‘oceans’ explores a highly economically efficient world and strong uptake of renewables to reduce emissions. There is some divergence between the two scenarios by 2060, but in terms of fossil fuel demand in 2030 they produce similar results – which are also close to BP’s and EIA’s forecasts.

Going back to the comparison between DNV GL and BP, the contribution from the main energy sources to the total primary energy by 2035 is revealing. In terms of oil, DNV GL predicts a 27% contribution by 2035 while BP predicts 29%, which is close. And the same applies to gas with 27% against 25%. Interestingly the total oil and gas contribution to total primary energy by 2035 is the same, at 54%. Incidentally, the EIA predicts this combined contribution to be about 56% by 2040 – close.

The marked difference is in terms of coal where DNV GL predicts a 12% contribution in 2035, while BP’s estimate is almost double at 23%. The difference is almost entirely accounted for by renewables, with DNV GL predicting a 22% contribution and BP at 10%. This implies that the switch in DNV GL’s forecast is not from coal to gas but largely from coal to renewables.

So the key factor is whether this switch is borne out by facts on the ground. As Figure 4 shows, the contribution from coal to total primary energy has remained roughly constant for over the last 40 years. All indications are that in absolute terms coal consumption may stay at the same level as now. This is also EIA’s forecast. Even BNEF forecasts that by 2040, global coal generation will be only 5% down from where it is today. That would impact oil and gas demand.

Demand for gas has been held back by two main factors. One is rapid growth in renewable power. In Europe, this has led to the mothballing of some gas-fired power stations as rising wind and solar generation pushes down wholesale electricity prices. The other is that coal remains cheaper than natural gas in many parts of the world.

The need for regulatory help to drive out coal explains why all the big oil groups support the taxation of carbon emissions – a measure which could make coal more expensive relative to gas. But so far it has been adopted only sporadically around the world.

Coal is not disappearing in Asia. In much of Asia, but also in Europe, it is coal that undercuts unsubsidised gas on price. As a result, the rapidly falling cost of renewables – even though still subsidised and non-despatchable – is putting more pressure on gas than on coal.

In China coal is cheap and available domestically, thus avoiding dependence on others and security of energy supplies challenges. It is similar in India. And in Europe, Germany, Poland and Turkey do not appear to have any plans to stop using coal.

No matter how hard China tries to find alternatives, coal is likely to remain its most important energy source for decades to come. For that reason CCS is virtually inescapable for China – at least after 2030.

What is needed is further cost-reducing technological developments and making sure that new coal-fired plants are ‘CCS-ready’, so that they can be easily retrofitted once the technology is affordable after 2030.

The conclusion from the above is that what happens to coal over the next two decades will be a crucial factor on how the global energy mix develops. Will it stay or will it go? Not an easy question to answer.

Another challenge is that natural gas producers portray their product as a ‘bridging fuel’ between the eras of hydrocarbons and renewables. The risk for the industry is that advances in battery technology, which allow surplus wind and solar power to be stored for future use, could allow the world to leapfrog gas direct to renewables. However so far, while batteries can deal with short-term fluctuations in renewable power, they cannot yet address seasonal variations.

Finally, technological advancements are coming so fast that they keep bringing unpredictable changes, often with far reaching effects and implications.

Implications

An important implication of peak energy demand is that with abundant supplies competition between producers will increase. The energy market will become much more competitive and cost-driven.

Globally, investments in fossil fuels will more than halve from around $3.4 trillion/yr today to $1.5 trillion/yr in 2050, according to DNV GL, while non-fossil energy expenditures show the reverse trend, increasing fivefold from around $500bn/yr today to $2.7 trillion/yr in 2050. But also according to DNV GL, the pleasant surprise is that the world can afford the transition. The amount of money spent on energy will not change much.

The energy future will be one of more intensive competition and reduced oil demand. Gas will be the largest energy source by 2034, but its share of the energy mix will start to decline from 2040 onwards. As a result, the oil and gas industry will intensify its focus on cost efficiency to remain competitive against renewables. And so far producers appear to be finding ways to deliver gas more economically. But that also means that low prices are here to stay.

However, the positive take for natural gas from DNV GL’s Outlook, supported by other outlooks including BP and Shell, is that it will continue as an important contributor to global primary energy to 2050. Gas is set to perform much better than other fossil fuels over the coming decades.