New Cold War Disrupts Global Gas Market [NGW Magazine]

The US-China trade war is increasingly looking like the start of a new Cold War. The long-term implications for the global gas market are huge in terms of consumption and production growth, international gas competition and preferred method to import gas, especially for China.

New Cold War

There’s a great deal of debate about the Trump administration’s motive for starting its trade war with China. One school of thought argues Trump is “simply” attempting to level the economic playing field between China and the US, in which case it’s just a matter of time before the world’s two economic heavyweights strike a trade deal.

Another school claims the administration is attempting to pre-empt the rise of a rival superpower, in which case the trade war could become a permanent new feature of the global economy.

As time passes and the war deepens with tit-for-tat tariffs, it is looking more and more like the latter, especially given the extreme demands of the US trade team. China is the most powerful of its geopolitical rivals. This strategy is like the one successfully pursued by Ronald Reagan in the 1980s: the US president forced the Soviet Union into an arms race it could ill afford, rather than negotiate a truce with it.

In the National Security Strategy of the States of America, released in December 2017, the Trump administration warned of a new era of “great power competition,” citing China and Russia in particular. These foreign powers are attempting to “reassert their influence regionally and globally,” and they are “contesting [America’s] geopolitical advantages and trying [in essence] to change the international order in their favour,” it said.

In a speech to The Hudson Institute in October 2018, vice-president Mike Pence reiterated these points, especially in regard to China. Pence said: “After the fall of the Soviet Union, we assumed that a free China was inevitable. Heady with optimism at the turn of the 21st century, America agreed to give Beijing open access to our economy and we brought China into the World Trade Organization.… America had hoped that economic liberalisation would bring China into a greater partnership with us and with the world. Instead, China has chosen economic aggression, which has in turn emboldened its growing military.”

In terms of the so-called ‘Made in China 2025’ initiative, Pence said: “[T]he Communist Party has set its sights on controlling 90% of the world’s most advanced industries, including robotics, biotechnology, and artificial intelligence. To win the commanding heights of the 21st century economy, Beijing has directed its bureaucrats and businesses to obtain American intellectual property – the foundation of our economic leadership – by any means necessary.” The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), America’s pre-eminent policy think-tank, has referred to ‘Made in China 2025’ as “a real existential threat to U.S. technological leadership.”

The US ambassador to the United Nations for the first two years of the Trump administration, Nikki Haley, wrote in Foreign Affairs – CFR’s flagship journal – in July: “China poses intellectual, technological, political, diplomatic, and military challenges to the US … China requires a response that is not just ‘whole of government’ but ‘whole of nation.’ Fortunately, there is support across the political spectrum for countering China’s new aggressive policies. We must act now, before it’s too late. The stakes are high. They could be life or death.”

Global Gas Market

The global gas market in 2040 under a New Cold War scenario will have little in common with the fond imaginings of the IEA’s New Policies scenario. In the latter case, economic growth will be higher and gas demand will also grow significantly faster (see Table 1).

Strong economic growth has helped drive global gas consumption higher since the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991, and especially since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. But with economic globalisation thrown into reverse, growth in the global economy and gas demand will be slower. Global economic growth averaged 3%/year during the 1947-91 Cold War, 0.4% percentage points less than projected by the IEA in the base case over the long term.

Since improvements in energy efficiency should be similar under either scenario – and could increase in a more geopolitically-charged world as security of supply fears rise – a 0.4 point decline in global economic growth should translate into a disproportionately large cut in gas demand growth. Global gas demand rises by third to 4.987 trillion m³ to 2040 in New Cold War, compared with almost a half under the New Policies scenario.

Slower gas demand growth in New Cold War leads to slower production growth and less revenue available for reinvestment thanks to lower volumes and prices, and less international trade. Global gas trade increases over half to 1.191 trillion m³ between 2017 and 2040, compared with two-thirds in New Policies Scenario.

LNG dominates growth in international trade under New Policies scenario, less so in New Cold War. Global LNG trade increases a whopping 134% in the former – exactly twice the rate for trade as a whole – increasing its share of international gas trade from 42% in 2017 to 59% in 2040. Pipeline trade increases by less than a fifth to 532bn m³. The IEA wrote: “China is the only region that shows a noticeable growth in trade via pipeline, mostly from Eurasia.”

New Cold War also assumes China is the one region to significantly ramp up pipeline imports of gas (to be discussed in greater detail in the next section), as other major gas importing regions such as Europe and India are likely to side with America, or at least be neutral, through 2040. Despite a rapid build of the Chinese navy in recent years, the US should continue to dominate the high seas for most, if not all, of the 2017-40 period.

Global LNG trade almost doubles between 2017 and 2040 in New Cold War, while pipeline trade increases by a quarter. The share of LNG in international trade increases to 53% over the period, whereas pipeline trade loses just 11 percentage points – compared to 17 points under New Policies scenario.

Chinese Gas Market

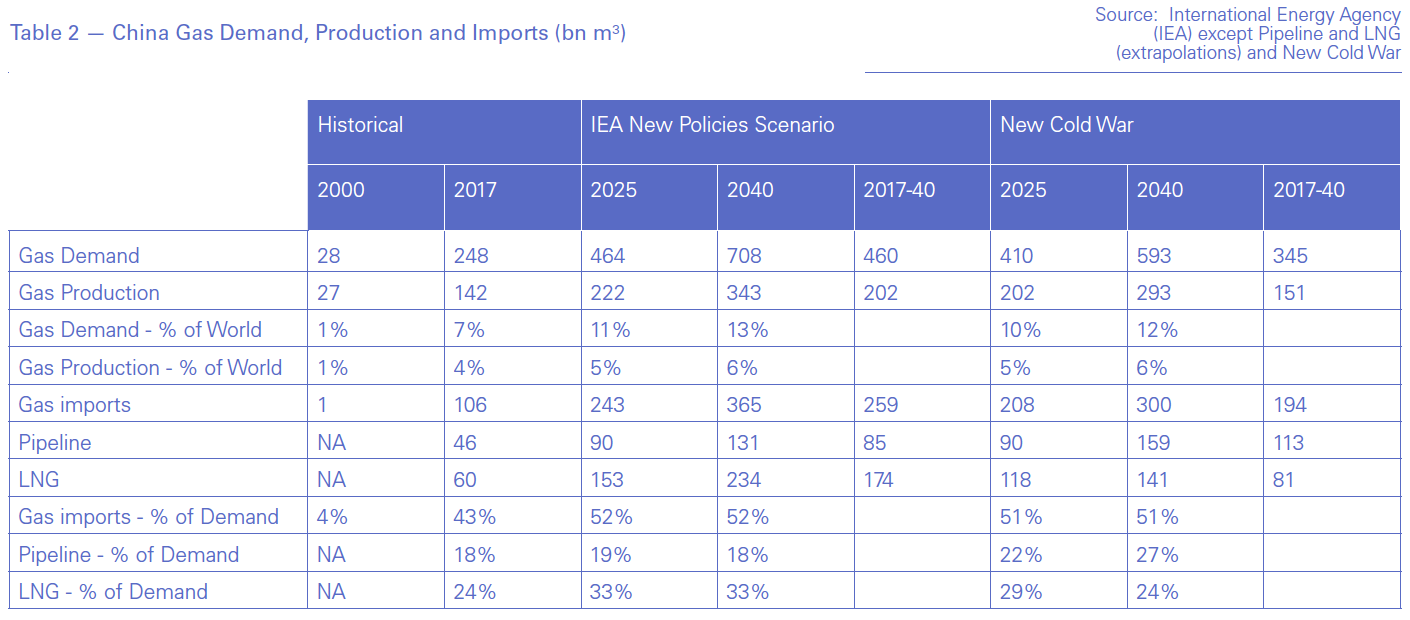

In a New Cold War scenario or not, China will be the major driver of global gas demand growth and trade in the long term, assuming rapid economic growth continues and the government sticks with its Blue Skies policy push to switch from coal to gas in industry and buildings (see Table 2). Exceptionally strong gas consumption growth in 2017 and 2018 in fact led the IEA to revise Chinese gas demand upwards by a massive 100bn m³ for 2040 in its most recently released New Policies scenario.

But security of supply has been a concern of Beijing in the past, and will only become a more important policy driver moving forward. Based on projections in the IEA’s New Policies Scenario, China will import 52% of its gas in 2040 and 82% of its oil. For 2017, the figures were 43% and 69% respectively.

This is despite a substantial forecast increase in Chinese gas output, especially unconventional gas in the post-2025 period.

New Cold War scenario assumes growth in both Chinese gas demand and output slip at the same proportion as in the rest of the world as a whole. In fact, China’s economic growth, and hence gas consumption, could be knocked proportionately harder because the Chinese economy has benefited relatively more from globalisation, while much of its industry has been developed for the now trade-constrained US market. On the gas production front, Beijing could ramp up incentives to boost output in response to security of supply concerns.

Despite these relatively conservative assumptions for consumption and production, China’s gas import dependency rate still increases 8 percentage points to 51% between 2017 and 2040 in New Cold War – albeit with total imports almost a fifth less than New Policies Scenario at 300bn m³ at the end of the period.

Since the middle of last decade the Chinese government has attempted to rapidly ramp up gas imports by pipeline from Russia and the former Soviet republics of central Asia, but with limited success for several reasons. These include the relatively high cost of pipeline gas from these countries compared with LNG, eastern Siberia being in an early state of gas development; and assorted political problems in central Asia.

The third line of the 55bn m³/year Turkmenistan-China gasline did not come into service until 2014. The Power of Siberia pipeline, which will eventually carry 38bn m³/yr is scheduled to start at the end of this year. Another pipeline is also under consideration, running from west Siberia, which would allow Russia to divert supply from Europe.

New Cold War assumes Chinese gas imports by pipeline will more than triple to 159bn m³/yr between 2017 and 2040, representing almost three-fifths of the country’s increase in total international trade. LNG imports more than double to 141bn m³/yr over the period. In contrast, Chinese pipeline imports of gas less than triple to 131bn m³/yr in New Policies scenario, whereas LNG imports almost quadruple to 234bn m³/yr.

LNG Competition

The combination of significantly less global gas trade over the next 20 years than had been foreseen and China’s greater success in sourcing pipeline gas from Russia and central Asia will contribute to far greater competition for international LNG markets than outlooks like New Policies scenario would indicate.

The IEA argues the roster of new LNG suppliers will become increasingly diverse later in the outlook period under New Policies scenario, expanding to countries such as Argentina and Mozambique. The top five LNG producers continue to dominate through 2025, accounting for over 80% of total production growth, whereas in the 2025-40 period the top five account for less than 40% of the total. The IEA wrote: “[O]ur analysis suggests that large-scale greenfield projects can also find a place in the new gas order.”

But with 126bn m³/yr less global LNG trade in 2040 under New Cold War than New Policies scenario, and the bulk of the difference arising over the 2025-40 period – most liquefaction projects that are to be completed by 2025 are already under construction – we should expect new entrants into LNG to be at a distinct disadvantage. Greenfield projects as a rule are more expensive than brownfield ones, of which the largest is the Qatari expansion.

The biggest winners under New Cold War through 2040 will be traditional LNG producers with distinct cost and geographical advantages, such as Qatar – now that it has ended its self-imposed project moratorium on North Field – and Russia, and Australia and the US as well. Qatar and Russia benefit from favourable shipping costs to the Asia and Europe, the two largest gas import markets, while LNG exports from Australia and the US should gravitate towards Asia.

However, the US will be the biggest LNG loser later in the 2017-2025 period in New Cold War. Not only will US LNG producers be shut out of the massive Chinese LNG market, but flexible contract terms for many liquefaction projects in a world of less than expected gas consumption will cause them to run far below capacity until the second half of next decade.

This, along with increasing concern about security of supply among major importers – especially China – could lead to a renewed age of firm delivery contracts for all LNG projects.

To conclude, the global gas market will be very different in a world dominated by superpower rivalry from the one based merely on economic competition.