Morocco turns to LNG in the face of pipeline insecurity [Gas in Transition]

Morocco is the latest country to enter the LNG market. Like Europe’s expansion of its LNG import capacity, the motivation is the loss of pipeline supplies from a neighbouring exporter, owing to a breakdown in political relations. This is not how it was supposed to be.

Large infrastructure projects – pipelines – were supposed to bind countries together in mutual economic benefit. However, Algeria, which has sufficient alternative export capacity, has been prepared to use gas as an economic lever in its dispute with Morocco and Spain over the Western Sahara.

Transit gas truncated

Algeria cut off gas supplies to Spain through the Maghreb-Europe pipeline, which passes through Morocco, in the fourth quarter of 2021.

Morocco had received a small proportion of the transit gas as a royalty, and consequently found itself unable to supply its two gas-fired power stations, Tahddart and Ain Ben Mathar. Together these have 1,735 MW out of total installed capacity in the country of just over 11 GW. The two plants consumed most of the Algerian gas with just over a tenth used by industry.

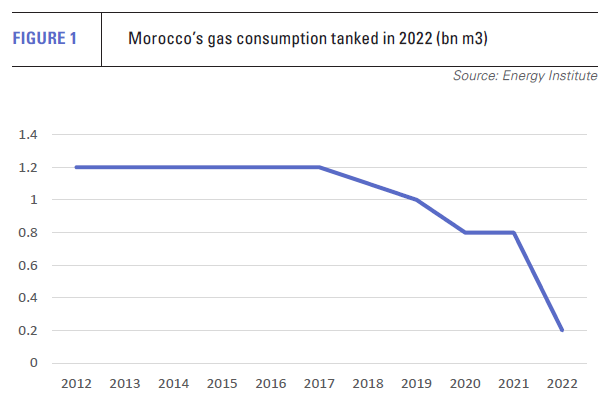

Moroccan gas consumption fell to just 0.2bn m3 last year, according to Energy Institute data (see figure 1), down from 0.8bn m3 in 2021 and 1.2bn m3 in 2017. The gas consumed came from domestic production, which is small, and reversed flows via the section of the Maghreb-Europe pipeline which links Morocco with Spain.

LNG market entrant

Gas continued to flow from Algeria to Spain via the 756-km subsea Medgaz pipeline, but as Spain otherwise sources its gas imports as LNG, Morocco became a defacto LNG consumer for the first time.

This position has now been cemented by the signing of a deal between Anglo-Dutch LNG major Shell and Morocco’s power and water utility ONEE in July for 0.5bn m3/yr of regasified LNG for 12 years. The gas will arrive in chilled form at Spanish LNG import terminals before being sent south via the Maghreb-Europe pipeline.

This position has now been cemented by the signing of a deal between Anglo-Dutch LNG major Shell and Morocco’s power and water utility ONEE in July for 0.5bn m3/yr of regasified LNG for 12 years. The gas will arrive in chilled form at Spanish LNG import terminals before being sent south via the Maghreb-Europe pipeline.

Morocco looked at the construction of on and offshore LNG import terminals, but the availability of floating regasification and storage units (FSRU) dried up in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent rush by European countries to secure FSRUs to expand their own LNG import capacity.

As Spain already has spare regasification capacity, but lacks the export infrastructure to send gas further into Europe, using the existing pipeline infrastructure made sense both from an economic point of view and in terms of the speed with which gas could be supplied.

Power exports turn to imports

Morocco's loss of Algerian gas also had another impact. In 2021, Morocco was a net exporter of power to Spain via two interconnectors, which together have a capacity of 1,400 MW. The country’s power surplus, in combination with its largely undeveloped renewable energy resources – both solar and wind – have been widely touted as a basis for the expansion of green electricity exports to Europe.

The start of reversed pipeline gas flows in late June 2022 allowed the reactivation of the Tahddart and Ain Ben Mathar gas plants in July last year, but the high cost of LNG in 2022, and the impact on Morocco’s gas subsidy bill, meant imports were kept to a minimum.

Owing to the inactivity of the gas plants, last year there was no power surplus and instead Spain exported on a net basis to Morocco..png)

Gas’ role in Morocco’s climate plans

Morocco’s generation mix is dominated by coal. According to ONEE, the country has 4,641 MW of coal-fired generation. Fossil fuels combined last year generated more than 80% of the country’s electricity, owing in part to very low hydropower output, the result of drought conditions.

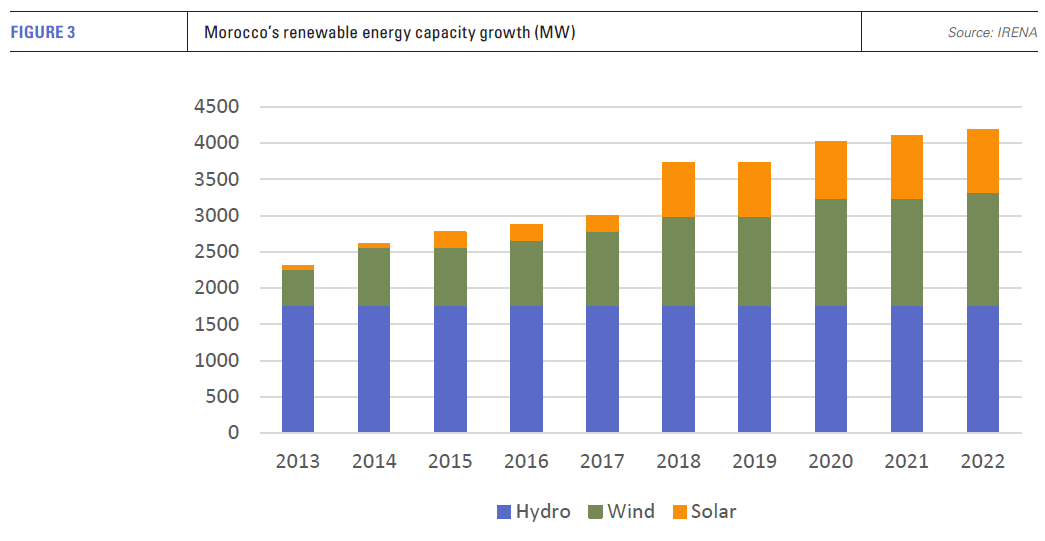

In line with its climate goals, Morocco intends to phase out its coal-fired generation completely by 2050. However, renewable energy capacity is growing only slowly (see figure 2).

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, the country’s hydro capacity has remained at 1,306 MW for the last decade, excluding pumped storage. Installed solar is 858 MW, of which 540 MW is concentrated solar power and the remainder solar PV, while wind has grown from 1.022 GW in 2017 to 1.556 GW last year (see figure 3).

More wind and solar farms are under construction as well as two pumped hydro projects, which will add flexibility and resilience to the electricity grid. But the capacity of generation projects under construction – about 800 MW of wind and 1 GW of solar – remain relatively modest in terms of the amount of electricity they will actually generate.

Increased gas-fired generation is, in any case, a central part of the plan to phase out coal. The government is targeting an additional 2,400 MW of gas-fired power plants by 2030. In May, ONEE issued a tender for construction of a 900-MW open-cycle gas-fired plant to be sited close to both the Al-Wahda dam and the Maghreb-Europe gas pipeline.

Increased gas-fired generation is, in any case, a central part of the plan to phase out coal. The government is targeting an additional 2,400 MW of gas-fired power plants by 2030. In May, ONEE issued a tender for construction of a 900-MW open-cycle gas-fired plant to be sited close to both the Al-Wahda dam and the Maghreb-Europe gas pipeline.

Domestic production hopes

Rabat is also pinning its hopes on a number of recent gas discoveries in the country, which could expand the current low level of domestic gas production.

Chariot Energy operates the 1,794-km2 Lixus offshore licence in nearshore water depths of up to 840 m. The licence has two discoveries, Anchois-1, with contingent resources of 361bn ft3 (10.2bn m3) and the more recently drilled Anchois-2, which identified dry gas across seven reservoirs with about 150m of net pay, according to company reports.

Chariot says that the Anchois gas field now has contingent resources of 637bn ft3 with additional on-block exploration potential. Contingent resources assess potentially recoverable gas, but not the economic viability of recovery. The spread of gas across multiple reservoirs could be problematic.

Nonetheless, Chariot completed the front-end engineering and design of key components of the Anchois gas development in March, at which point it said engineering, procurement and construction proposals had been requested.

The development will initially consist of three subsea production wells, including Anchois-2. The gas will be processed at a facility onshore and a tie-in agreement to the Maghreb-Europe pipeline has already been signed. Production capacity initially will be 100mn ft3/d.

Chariot also signed in early August a new petroleum agreement for exploration on the Loukos onshore licence, which lies adjacent to its offshore licences.

Predator Oil & Gas and SDX Energy are also active in the Moroccan gas sector. In June, Predator announced that its MOU-3 well had identified two new potential gas reservoirs on the Guercif Petroleum licence onshore. The company has identified six targets in addition to the newly-discovered shallow gas zones.

SDX Energy in November last year announced two discoveries from the SAK-1 and KSR-20 wells, the first of which has already been linked up to SDX’s existing infrastructure. According to the company, the discoveries open up a new area to the north-west of SDX’s current production zone.

The company has four concessions in the Gharb basin in northern Morocco. In June, SDX announced the renegotiation of one of its gas sales agreements, allowing it to expand its summer exploration programme.

Owing to the loss of Algerian imports, gas prices are high making even relatively small discoveries commercially viable. In addition, Morocco has an attractive fiscal regime for gas production, including a total exemption from corporation tax for 10-years. The government’s stake in licences is capped at 25% and exploration and production benefit from a range of other tax exemptions.

Owing to the loss of Algerian imports, gas prices are high making even relatively small discoveries commercially viable. In addition, Morocco has an attractive fiscal regime for gas production, including a total exemption from corporation tax for 10-years. The government’s stake in licences is capped at 25% and exploration and production benefit from a range of other tax exemptions.

As a result, investment in gas is arguably more attractive than the electricity sector, where no competitive wholesale market exists, transmission and distribution fees are high and infrastructural limitations in the domestic grid are large.

Although it remains early days for these discoveries, they could make a significant difference to Morocco’s gas balance.

However, ONEE’s willingness to sign up to a 12-year LNG supply deal with Shell indicates that it, at least, expects domestic gas in the short-to-medium term to meet only a proportion of the country’s demand, and there is no clarity, beyond LNG, as to how new gas-fired plant will be supplied.

Long-shot pipeline option

Another gas supply possibility are the various plans for a Nigeria-Europe gas pipeline. There are two versions of this scheme, both of which would require a host of intergovernmental agreements and billions of dollars in investment for a project which would take years to complete.

One plan is to take the pipeline directly north through Niger, where a coup has raised questions about cooperation and security, and into Algeria, which would be of little benefit to Rabat, given the two countries’ parlous relations.

The second option is for the pipeline to skirt the West African coast and come through the Western Sahara to link up with the now under-used Maghreb-Europe pipeline, which would provide Morocco with plentiful gas for its own economy, as well as transit fees for the onward export of gas to Europe. Some agreements have been signed, but the project is a vast undertaking and dependent on gas supplies from Nigeria, where both oil and gas production experience recurrent interruptions.

Western Sahara remains a flashpoint in Algerian-Moroccan relations

The dispute over the Western Sahara is a flash point for Algeria, a socialist republic, and Morocco, a constitutional monarchy, two countries which have grown apart since independence.

Spain withdrew from the Western Sahara in 1975 and it was occupied by Morocco. Mauritania rescinded its claims to parts of the territory. The occupation was resisted by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) and its armed wing the Polisario Front. Algeria supports the SADR and independence. Morocco views the Western Sahara as its sovereign territory.

Algeria has provided military support to the Polisario Front, as well as providing refuge for its leaders and establishing Sahrawi refugee camps within its borders. Algiers has accused Rabat of supporting the Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylie and the Islamist Rachad Movement, both of which it categorises as terrorist organisations.

Morocco’s claim that the Western Sahara is sovereign territory is not recognised by the UN. Only the US, under Donald Trump, recognised the claim when Rabat normalised its relations with Israel. In July this year, Israel also changed its position in support of Morocco. In March 2022, Spain expressed its support for Morocco’s autonomy plan for the Western Sahara.

The UN and the International Court of Justice have ruled that Morocco’s attempts to annex the territory are illegal. The UN categorises the Western Sahara as a non-self-governing territory. A referendum on independence, agreed in the late 1980s, has never been held.

The Western Sahara’s primary resources are its oceanic fishing grounds and large reserves of phosphate rock, which is used in the production of phosphate fertilisers, as well as containing significant amounts of uranium. Given its high solar irradiance, the territory has huge solar potential as well as a substantial wind resource.