Mexico asserts resource sovereignty [NGW Magazine]

The final investment decision (FID) on the Energía Costa Azul (ECA) LNG project in Mexico, issued last year, opened up a new option for companies seeking to export US natural gas. In the difficult market conditions, half the capacity is being offtaken by a partner in the plant, the French marketer Total.

But in late December, the Mexican energy ministry issued new regulations covering the permitting process for the import and export of fuels.

“All changes to legislation are made due to a new vision of the new federal Mexican administration called the ‘energy sovereign policy’, which is intended to strengthen Mexican national energy entities in the energy sector,” Claudio Rodriguez Galan, a partner in Thompson & Knight’s international energy practice, told NGW. These state-owned entities being favoured by the president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador include national oil company Pemex and electricity utility CFE.

While the most significant changes affect refined fuels, the new rules also affect natural gas. Specifically, importers and exporters of gas will need to provide more detailed information on volumes and infrastructure. In addition, the Mexican government will only grant future LNG export permits for excess gas above what is required to meet domestic needs.

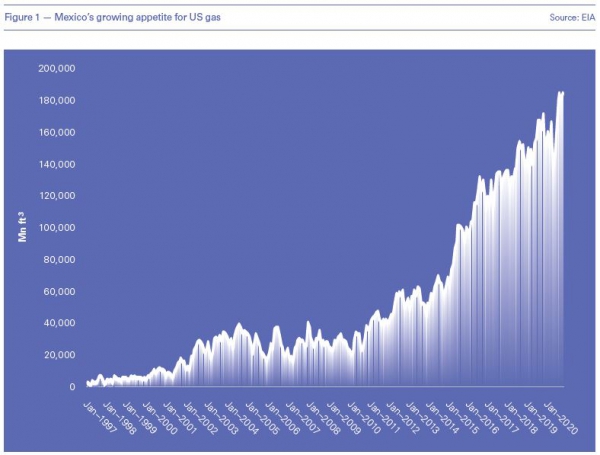

This poses a potential challenge given Mexico’s increasing reliance on foreign gas supplies. Rodriguez Galan noted that gas imports into Mexico had grown steadily over the past decade and that this might be viewed as going against the energy sovereign policy. Nonetheless, with domestic production limited and declining, imports are necessary.

“Mexico's domestic production is only at 3.9bn ft3/day and struggling and there are still strong drivers for demand,” Erin Blanton, a senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University SIPA, told NGW. “We saw Mexico's gas demand go up in 2020 despite the pandemic and economic impact. So the fundamentals are strong, especially as US pipeline gas is so much cheaper than imported LNG.” She added that volumes from the Waha hub in Texas were now displacing imports of LNG via Mexico’s Manzanillo terminal.

Indeed, Mexican imports of gas from the US reached record highs in 2020 as pipeline capacity grew, totalling 6.2bn ft3/day in October, the latest month for which data from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) are available. And imports appear set to grow further still, owing to both ongoing pipeline capacity expansions and increasing demand.

“A few days ago CFE published its 2021-27 business plan, which shows an important increase in thermal power generation by the Mexican state. This means that even more gas is needed,” said Rodriguez Galan. “Therefore, such legislative changes might be a product of securing more gas for the Mexican state (CFE) which might mean that private entities will face more struggles to import gas for their own projects if such imports affect the availability (and ultimate energy sovereignty) of gas for CFE.”

Obstacles for LNG

This prioritisation of gas for domestic use could make it more challenging for LNG export projects to move forward in Mexico, coming as a blow just after the FID on ECA LNG bolstered interest in the country’s export potential. The move should not affect ECA LNG itself, with operator Sempra Energy having already received its export permit. But other projects have also been proposed, and their backers may find the permitting process more challenging.

Mexico Pacific Ltd (MPL) is proposing to build an LNG export terminal at Puerto Libertad in Sonora State, and had said before the regulatory changes that it could make an FID by the end of 2021.

Separately, Singapore-based LNG Alliance is proposing to build the Amigo LNG terminal. That project has received authorisation from the US Department of Energy to export US gas to Mexico and then re-export it as LNG, but still has regulatory hurdles to clear in Mexico.

Both projects would be on the Sea of Cortez in the Pacific, and would pipe in and liquefy Permian gas for export to Asia – the same approach that ECA LNG is taking. The appeal of exporting LNG from Mexico is that it saves both time and money compared with shipping the fuel from the US Gulf Coast. And ongoing delays in transiting the Panama Canal, which have contributed to the recent spike in Asian spot prices, have made the option of shipping directly from North America’s Pacific Coast look all the more attractive.

On the other hand, regulatory uncertainty threatens to diminish the appeal of building liquefaction capacity in Mexico.

“The legislative changes will deter further LNG investment as they prioritise domestic gas use and only allow for the shipment of excess gas,” Blanton said. “It is a huge investment to build an LNG export terminal and with the threat of ever-changing rules and permit requirements, those risks will certainly make investors wary.”

She expects pushback from companies that stand to be affected by the changes, however. “The changes will be challenged in court, ie with parties arguing that they violate the [US–Mexico–Canada Agreement, or USMCA] but the uncertainty will remain and given that every year of delay in an LNG export project is a year that another project around the globe can make an FID and sign contracts with customers, it will continue to set back future Mexico export projects,” she said. As a result, Blanton is sceptical about how much LNG export capacity would be built in the country.

Rodriguez Galan noted that the USMCA has the last word under the legal framework in Mexico. Indeed, several injunction proceedings against legislative changes based on the energy sovereign policy had been filed and relief actions granted by the courts, he said. He also takes a slightly more optimistic view about LNG developers being able to find a way forward.

“The conditions, steady growth and size of Mexican market makes new projects feasible,” Rodriguez Galan said. “I think projects and investors will understand that decisions now by Mexican officials in the energy sector are not made based on the strict rule of law, but on the [energy sovereign] policy, which it is not necessarily written or based on the law, but even so, it is blindly followed by the ministry of energy, Pemex and CFE,” he explained.

“However, if investors understand this situation and they find new ways to submit their projects to the authorities (understanding their vision of the policy), then it is likely for them to develop new projects in Mexico,” he said. “As now everybody agrees, reading the law is not enough if investors do not understand the rationales imposed by the policy and the impact that it might have on their investments and projects.”

Thus, options appear to remain available for companies seeking to build LNG terminals and participate in Mexico’s gas industry. In addition, the abundance of US – and particularly Permian – gas increasingly available to Mexico could also mean that volumes are more than sufficient to meet the country’s domestic needs as well as demand from LNG exporters.

“At the end, I think the availability of gas in foreign markets shall suffice the needs of both private and state-owned companies,” said Rodriguez Galan. “If this happens, the changes in legislation shall decrease. However, if the availability of gas deceases in foreign markets, the ministry of energy will continue to change Mexican rulings to secure gas for CFE.”