Methane emissions regulation is getting tougher, much tougher [Gas in Transition]

Methane has been identified as a potent greenhouse gas (GHG), particularly over shorter time frames, and the impetus to control emissions of the gas is strong. In its report The Imperative of Cutting Methane from Fossil Fuels, published last October, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said that actions to tackle methane emissions from fossil fuel production and use were essential to limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

The primary targets, and the most cost effective, are the elimination of routine venting and flaring, alongside the rapid identification and repair of leaks.

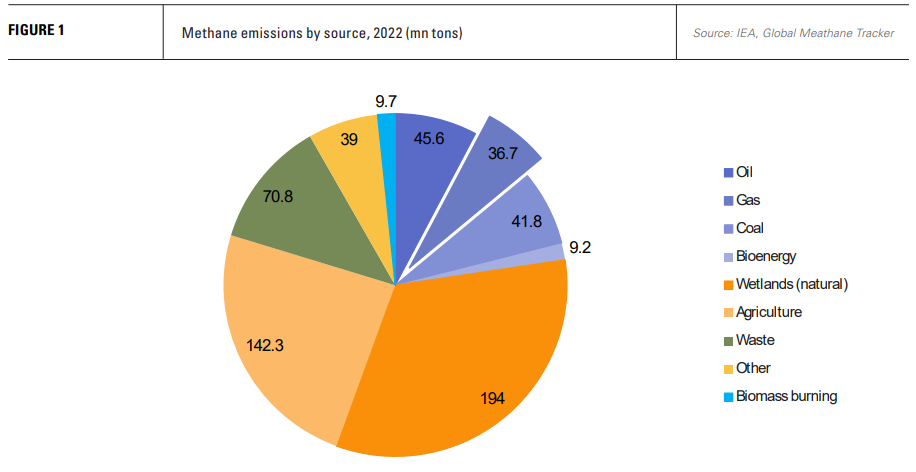

According to the IEA, fugitive methane emissions from LNG operations are relatively low. Liquefaction and shipping in 2022 resulted in methane emissions of just 0.4mn t, compared with the IEA estimate that fossil fuel operations generated close to 120mn tonnes of methane in 2020, nearly one third of those generated from all human activities.

However, this ignores methane emitted upstream to supply the feedstock on which LNG plants depend. With a raft of regulations hitting the market from this year in the EU and US, controlling methane emissions from all parts of the gas value chain is now central to sustaining a social license for LNG production and use.

INFO BOX: LNG – a small but important source of methane emissions: IEA

Methane leaks can occur at LNG liquefaction facilities from gas service valves, reciprocating compressors, pump seals or metering equipment as well as during the transfer of LNG to ships. During shipping, methane leaks can also occur if boil-off gas from the cargo is vented or used as propulsion but not fully combusted in the ship’s engines (methane slip).

The IEA estimates that total fugitive methane emissions from LNG liquefaction and shipping in 2022 were about 0.4mn t, equivalent to around 0.1% of total annual LNG transported globally. Shipping accounts for the majority and it is essential to ensure that boil-off gas is injected into engines or reliquefied rather than vented.

Manufacturers are increasingly promoting technologies that reduce methane slip, for example by recirculating exhaust gases, using high-pressure direct injection or methane oxidation catalysts.

Regulation has become more overtly obligatory

Tougher methane regulation is here and with it a much greater emphasis on obligatory as opposed to voluntary actions. Both in the EU and the US, regulation will extend to existing facilities and new developments, as well as including legacy operations, such as abandoned wells.

In Europe, the EU’s methane regulation is close to adoption. Following a deal between the European Parliament and European Council in November, an agreed text was endorsed by the Committee of the Permanent Representatives of the member states on December 15 and by the ENVI and ITRE committees of Parliament on January 11.

It now needs a final vote in a parliamentary plenary session and publication in the EU’s Official Journal before becoming law, which is likely before European parliamentary elections in June.

The regulation is wide ranging, applying to oil and gas upstream exploration and production, including inactive wells, temporarily plugged wells and permanently plugged and abandoned wells, fossil gas gathering and processing, gas transmission, distribution, underground storage and LNG terminals. There is an exemption allowing slower implementation for EU countries with more than 40,000 old wells and for offshore wells in deep water.

The regulation requires operators to report regularly on methane emissions at source level, including non-operated assets and obliges companies to carry out regular surveys on their equipment to detect and repair leaks. It also bans routine venting and flaring and restricts non-routine flaring to unavoidable circumstances. It also requires oil, gas and coal companies to carry out an inventory of closed, inactive, plugged and abandoned assets, such as wells and mines. Companies have to monitor the emissions of these inactive assets and adopt a plan to mitigate any emissions as soon as possible.

Some time is allowed to bring these new rules into practical operation. Routine inspections need to be completed 21 months after the regulation’s date of entry into force and the subsequent inspection period should be no longer than three years. With regard to monitoring and reporting, operators are required to deliver quantification of source level methane emissions within 18 months for operated assets and within 30 months for non-operated assets. Site level emissions measurement is required within 30 months for operated assets and within 48 months for non-operating assets.

In addition, operators need to submit a leak detection and repair programme to the relevant authorities within nine months of the regulation coming into force and within six months from the start of operations at new sites. The Commission may choose to specify minimum detection limits within 12 months and the regulation says that repair needs to take place immediately after a detection of a leak over the threshold and no later than five days for a first attempt and 30 days for a complete repair.

There is an exemption for offshore wells at a depth of more than 700 metres, provided evidence can be shown that emissions from these wells are likely to be negligible.

INFO BOX: Romanian oil site methane emissions valued at €90mn

A study coordinated by UNEP’s International Methane Emissions Observatory released in September 2023 estimated that oil production in Romania emitted about 120 kilotonnes of methane in 2019, at least two times more than the national inventory estimate. The lost methane was valued at about €90mn based on average prices at the Dutch Title Transfer Facility in the first half of 2023.

The study quantified methane emissions from onshore oil production sites in Romania at source and facility level using a combination of ground and drone-based measurement techniques. About 10% of the sites accounted for more than 70% of total emissions.

Major causes of methane emissions from oil production sites in Romania are the venting of gas through open-ended lines, followed by malfunctioning equipment. The study also found that sites associated with emissions of the dangerous gas hydrogen sulphide were better maintained and had a lower number of detected emission points compared with oil production sites without these emissions.

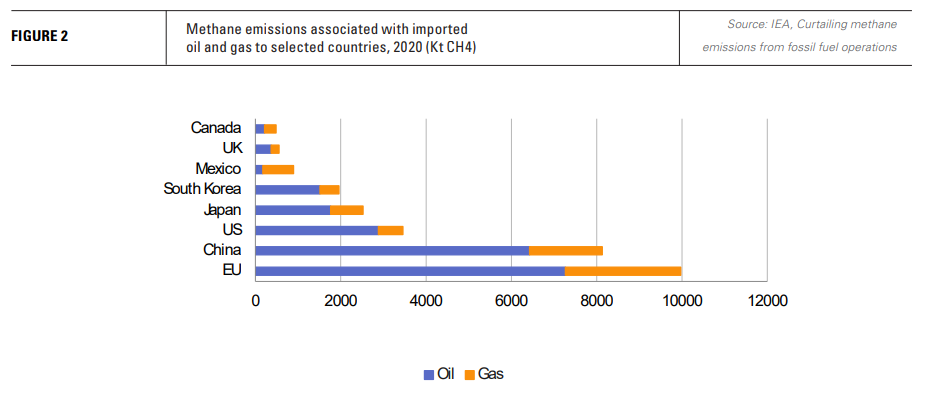

EU regulation will extend to imports

Given the growth in US-European LNG trade, one of the most significant aspects of the EU’s regulation is that, from January 2027, new import contracts for oil, gas and coal can only be concluded, if the same monitoring, reporting and verification obligations are applied by exporters. Prior to this, the Commission will establish methane performance profiles of importing countries and companies as part of a methane transparency database. It will also establish a super emitter rapid reaction mechanism.

January 2027 is some time off, but the requirement on contracts applies to all those concluded or renewed after the entry into force of the regulation, which should be in the first half of this year. For contracts concluded before the entry into force of the regulation, the principle of undertaking all reasonable efforts in relation to monitoring, reporting and verification applies.

Non-compliance will carry penalties, but these are to be decided at the national level and will depend on the approach of individual member states’ own regulatory authorities. According to the EU regulation, penalties must be effective, proportionate and dissuasive and shall include fines proportionate to the environmental damage and impact on human safety and public health. Periodic penalties are also foreseen to ensure operators put an end to infringements.

EU member states have to notify the Commission of their penalty regime 12 months after the regulation comes into force.

US EPA gets tough on methane

The toughening of the US regime surrounding methane emissions comes via the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Section 111 Methane Rule, which aims to prevent an estimated 58mn t of methane emissions between 2024 and 2028. Like the EU regulation, for the first time, the new rule addresses methane emissions from existing and new facilities.

The EPA rule covers standards for performance for oil and gas facilities which were built or modified after December 6, 2022 and provides emissions guidelines for GHG emissions from existing oil and gas facilities.

The former standards should come into effect this year, 60 days after the rule’s publication in the Federal Register, with exceptions for some equipment. The latter will take longer. They are guidelines which states must implement in their state air quality regulations for existing oil and gas facilities. They have two years to submit their plans and compliance must take place within three years, so potentially up to a five-year time frame (early 2029) to fully implement the rules in any given US state.

The rule extends the number of emissions sources to include dry seals, liquids unloading, super emitters and well closures. It allows the use of continuous monitors and other advanced technologies to detect leaks, rather than, as previously, only handheld technologies such as optical gas imaging.

The new regulations restore methane rules for the oil and gas upstream, which the previous Trump administration rolled back, strengthens emissions requirements for oil and gas production, including the addition of requirements to reduce routine flaring and requiring process controllers to be zero emissions.

It will phase out routine flaring of associated gas from newly constructed wells. It includes a two-year phase-in period for eliminating routine flaring of natural gas from new oil wells, and a one-year phase-in of zero-emissions standards for new process controllers and most new pumps outside of Alaska.

Monitoring of unintended methane leaks must be increased to at least once a quarter and the rule lays down specific timeframes for repairing leaks. It will also use third-party data to develop a super emitter programme to address large, intermittent emissions events, which are estimated to account for almost 50% of total methane emissions from the oil and gas sector.

The Section 111 Methane rule is likely to face legal challenge and is vulnerable to the US electoral cycle, as it could potentially be rolled back by a new administration, following presidential elections in November this year. If such a situation were to occur, there could be a significant mismatch between EU and US methane control complicating the agreement of new US-Europe LNG contracts.

Section 111 is not the only initiative on methane

The EPA rule is not the only initiative to address methane emissions in the US. The EPA has proposed an update to the GHG Reporting Program and there is a forthcoming rule to implement the Inflation Reduction Act’s Waste Emissions Charge (WEC). The Bureau of Land Management and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration have also proposed rules to limit methane emissions from other segments of the oil and natural gas sector.

The WEC for methane applies to petroleum and natural gas facilities that emit more than 25,000 t/yr of CO2 equivalent as reported under Subpart W of the GHG Reporting Program, that exceed statutorily specified waste emissions thresholds set by Congress, and that are not otherwise exempt from the charge. This covers on- and offshore petroleum and natural gas production, onshore natural gas processing, onshore petroleum and natural gas gathering and boosting, onshore gas transmission compression, onshore natural gas transmission pipeline, underground natural gas storage, LNG import and export equipment, and LNG storage.

The WEC starts at $900/t for methane emissions reported in 2024 and will rise to $1,200/t in 2025 and $1,500/t from 2026 onwards. The proposed rule has been published in the Federal Register and the EPA is seeking public comment until March 11.