Market reality hits Egypt’s gas [NGW Magazine]

Egypt had another busy year upstream in 2019 and this was showcased at the country’s annual petroleum show, Egyps 2020, held in Cairo February 11-13. Despite the upbeat theme – ‘North Africa and the Mediterranean: Delivering the Energy Needs of Tomorrow’ – 2020 is turning out to be a pivotal, if challenging, year for the energy, oil and natural gas industries worldwide. Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean as a whole are not immune to it.

Opening the conference, petroleum minister Tarek El Molla said that during the financial year (FY) 2018-19, the oil and gas sector contributed a quarter,or $89bn, to Egypt’s gross domestic product. He also reviewed Egypt’s Vision 2030 and the steps being taken for Egypt to become the regional energy trading hub.

This year, El Molla said: “We are focusing mainly on completing the petroleum sector’s ambitious Modernisation Project, as we exert efforts to expedite our plans to establish new petroleum projects in both upstream and downstream activities as well as infrastructure.”

A total of 29 international agreements and MoUs were signed during the event. Since the turnaround of the country’s oil and gas sector that started in 2014, Egypt has signed more than 82 gas and oil exploration deals. These reflect the great potential and promising opportunities of the Egyptian petroleum sector.

This is also attracting the attention of the US, which took the opportunity of the conference to request membership of the East Med Gas Forum (EMGF), headquartered in Cairo, as a permanent observer, which El Molla welcomed. France had officially applied for membership the month before.

More exploration and drilling

The completion of the Red Sea offshore bidding round in 2019, with licences awarded to Anglo-Dutch Shell, US major Chevron and Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala, confirmed the increasing interest of international oil companies (IOCs) in what the country has to offer.

The Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation (EGPC) also signed new agreements with Shell, US independent Apache and Malaysian state Petronas to develop projects in the Western Desert.

US ExxonMobil, while it is divesting upstream assets in Europe, has continued to cultivate the eastern Mediterranean. After buying offshore exploration blocks in Cyprus and Greece and one in Egypt in February 2019, this year at the event it signed a deal for the North Marakia block offshore Egypt, in the newly opened Herodotus basin. Welcoming this, El Molla said the “company's decision to work in Egypt among the other global petroleum companies testifies to Egypt's success in providing an investment-magnet atmosphere in the petroleum sector.”

Energean is close to completing its acquisition of Edison’s assets in Egypt. Its CEO, Mathios Rigas, confirmed the company’s commitment to Egypt and the investments in Abu Qir, NEA and the promising North Thekah, where drilling is now in progress (Figure 1). This is close to Zohr, Aphrodite and Glafkos, with results expected in March.

Wintershall DEA announced an 18-month development programme at Disouq and in the Gulf of Suez. It also signed a concession agreement for the East Damanhour block, situated west of Disouq.

A new entrant is Dragon Oil that agreed last month to buy BP’s Gulf of Suez assets in a $500mn deal. It also plans to invest an additional $650mn in Egypt over the next five years, buying operating assets in the Western Desert.

Eni continued its successful track-record with more discoveries in Egypt. Petrobel, equally owned by Eni and the EGPC, made new hydrocarbon discoveries at the Sidri lease in the Gulf of Suez.

Shell, which acquired acreage when it bought BG, plans to drill seven wells at West Delta Deep Marine (WDDM) phase 9B this year to produce initial reserves of close to 7bn m³ of gas. The company also aims to connect three other wells at Simian, Sapphire D and Sapphire East DC to 9B, targeting production of 12mn m³/day of gas to be piped to Idku LNG (Figure 2). It will also concentrate on exploration in Rosetta and its newly acquired offshore blocks 4 and 6.

On the other hand, Shell decided to sell its onshore assets in the Western Desert, in order to focus on offshore exploration and its gas business in Egypt.

During 2019 Egypt made 55 new petroleum discoveries in the Mediterranean, the Eastern Desert, the Western Desert, the Gulf of Suez, the Nile Delta, and Sinai. Of these 40 were crude oil and 15 natural gas discoveries. Even though mostly small, they add to the country’s proven oil and gas reserves.

In order to attract more IOCs to invest in the country, EGPC signed a memorandum of understanding with Schlumberger International to create an Egyptian e-portal for research and exploration.

This will “use the latest technologies and advanced digital solutions to offer and promote investment opportunities for oil and gas search and exploration” in Egypt, it said.

Activity continues unabated in 2020, with Egypt hoping to sign 17 new exploration agreements. There are also plans to drill 86 wells.

Two days after the conference, the petroleum ministry signed non-binding agreements with five IOCs – Shell, Chevron, BP, French Total and ExxonMobil – for deep-water exploration in the western part of its Mediterranean exclusive economic zone. These are the first such agreements in a new promising region – WestMed – with drilling expected to begin next year. El Molla said that the government had opted for directly awarded contracts, giving priority to companies with advanced technology capable of drilling deepwater wells. With these agreements, all the majors are now becoming active in Egypt – a major achievement.

Gas production and exports

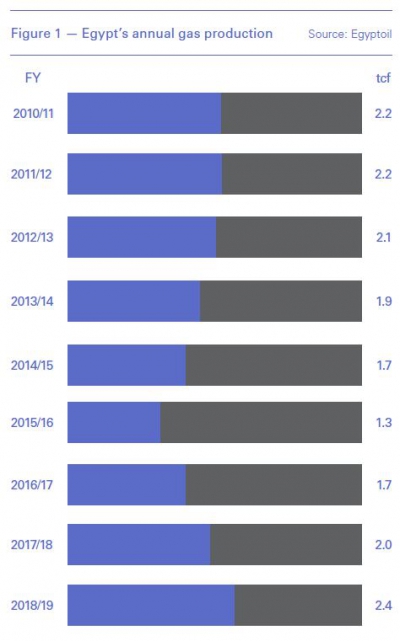

Egypt’s largest gas-field Zohr reached a production level of 76.5mn m³/day at the end of 2019. Development has now been completed, and Eni, the field operator, has said production should reach 90.6mn m³/day by the end of this year.

This, and development of other smaller gas-fields, helped Egypt achieve record gas production by December 2019, over 200mn m³/day, leaving a surplus that fed LNG exports. Actual LNG exports reached 4.8bn m³ in 2019. Complicating the picture though are some relatively expensive and politically motivated pipeline imports from Israel through an onshore pipeline (see below).

Total oil and gas production - crude oil, condensates and natural gas - increased in 2019 to a record 1.9mn barrels of oil equivalent boe/day, 7% up on 2018.

BP and its partner Wintershall DEA hope to add to this with completion of phase-3 of its West Nile Delta (WND) project, with the Raven field coming on-stream by the end of this year. On completion, WND should be producing an estimated 40mn m³/day, which would be a major boost to Egypt’s gas production.

With Zohr reaching plateau production and WND coming on-stream and domestic consumption expected to reach 187mn m³/day during 2019-20, Egypt expects to have close to 15bn m³ surplus gas production over this period, available for export. This does not allow for any impact from Israeli gas imports.

The petroleum ministry is targeting gas production of over 227mn m³/day by the end of 2021, so that it can maintain gas surplus for export.

During the past four years as many as 27 gas-field development projects were implemented with investments reaching $31bn, adding to a production rate of about 215mn m³/day.

Over 60% of natural gas is consumed by the country’s electricity sector. With ambitious plans to provide up to one fifth of electricity through renewables by 2022, rising to 42% by 2035, the vastly increased efficiency of the new Siemens power plants and the likelihood of more gas discoveries over the same period, surplus gas production looks like becoming a longer term feature.

Egypt is not neglecting renewables either. In November it completed the construction of the largest solar PV power complex in the world, the 1.8-GW Benban Solar Park.

What is also encouraging, is that the measures taken by the Egyptian government to reform the energy sector and reduce fuel subsidies are having a positive effect in reining in excessive energy use. More cuts are planned.

However, gas use is expected to rise by about 5%/yr, including the electricity sector, industry, households and transport.

The ministry of petroleum set up a committee to review gas prices in existing agreements, on a project-by-project basis following the collapse of the global oil and gas market, but without scaring investors off.

Based on this, state Egas, Shell and BP agreed to modify gas prices at the El-Burg marine concession (Figure 2) through a price index formula linked to the global price of crude, with a maximum price of about $5.88/mn Btu and a minimum of $/4.00/mn Btu. Egas hopes that this will accelerate development plans and thus increase production.

Egas also confirmed that similar negotiations are taking place with other IOCs. The outcome is that the average production cost of Egyptian gas is estimated to be $4/mn Btu.

Offsetting decline

Egas is aiming to develop 15 gas projects until mid-2022 with investments estimated at $18bn to compensate the natural decline in existing fields and increase production. They will include wells at West El Burullus, South Seth, North Tort, Salamat, Rahmat, Satis, Tennin, Merit, Aten, Tersa, and Salmon. These are expected to produce an additional 90mn m³/day – close to 45% of today’s production.

New concession licences awarded during the last two years, including the opening up of the WestMed region – and more concessions expected to be awarded this year – are expected to lead to significant new discoveries, adding to the country’s natural gas reserves and maintaining the country’s impressive gas production rate growth.

In the meanwhile, restructuring continues under the ministry’s ambitious Modernisation Project. El Molla outlined progress with the project that aims to develop and upgrade Egypt’s entire oil and gas sector in order to attract more investments, train new talent and enhance the sector’s contribution to Egypt’s economy and development further.

The development of this plan has taken three years and it aims to separate between policy making, organisation, and executive roles. It has now entered the implementation phase, to be completed by June 2021.

Contributing to this is the news that Egypt has paid $5.4bn of the debt to IOCs accrued in the previous seven years, with the remaining $900mn expected to be paid out by the end of this financial year.

Regional energy hub

Egypt aims to become a regional energy trading hub, especially for trading oil, gas and LNG, following major discoveries made in recent years, including the Zohr gas-field which holds an estimated 850bn m³ of gas.

In support of this aim, Wael Sawan, Shell’s upstream director, said at Egyps 2020: “We remain committed to Egypt and see our future in supporting the government’s energy hub vision by growing Shell positions across the offshore and LNG value chain. This is where we can best leverage our expertise, deliver the strongest added value to Egypt, and optimise our portfolio.”

The aim to become a regional energy hub was assisted by the resumption of gas exports to Jordan. This was boosted further by the start of gas flows from Israel to Egypt in January, as part of an export deal involving 85bn m³ of gas over a 15-year period from Israel’s Leviathan and Tamar gas-fields. In normal circumstances, Israeli gas could contribute to increasing Egypt’s surplus gas available for LNG exports.

But by early February militants bombed the pipeline transporting the gas in northern Sinai, reminding everybody of the risks that lurk under the surface in an inherently unstable region. However, the Israeli energy ministry said the flow of natural gas – which is reportedly delivered under a political rather than commercial arrangement between the two countries and with US involvement, – was “undisturbed.”

The biggest challenge to Egypt’s hub aspiration and to gas exports from the region in general, comes from the fast-developing global gas glut, brought about by a booming US gas and LNG production and a drop in Chinese demand – even before the impact of coronavirus – that has brought prices down to unprecedentedly low levels and threaten LNG trading worldwide. A number of new LNG projects around the world from the US, Canada, Qatar, Russia, Mozambique and Nigeria is expected to lead to an even bigger oversupply later this decade: much will depend on economic recovery particularly in Europe and Asia.

During Egyps 2020 participants expressed concern about the imminent future of Egypt becoming the eastern Mediterranean gas hub, as new LNG export contracts are not being signed: the buyers are asking too low a price.

2020 challenges

There are clear signs that this global gas glut is not just another cycle, but it is due to the ever-increasing volumes of US LNG exports and the inexorable increase in the use of renewables displacing fossil fuels, driven by a global shift towards green energy and fuel decarbonisation.

Even though LNG prices are likely to recover, most international analysts and experts expect that global gas and LNG markets will remain “lower for longer.”

As a result of low market prices – that do not even match the cost of production – Egypt cancelled several LNG tenders during the last quarter of 2019. It preferred to shut in most LNG production in September and October. This is continuing to be the case, with 2020 expected to be even more challenging due to plunging global gas prices. Also gas exports to Jordan are stuck at low levels – the contract is limited to 7mn m³/day.

Unable to export its LNG and with the domestic gas market saturated and unable to absorb the current surplus, but also due to national pipeline network pressure limitations, Egas was forced to cut gas production this year down to 175mn m³/day from the 200mn m³/day achieved in December. And that is while it imports more expensive Israeli gas by pipeline, reported to cost more than $6.00/mn Btu on delivery. Egypt receives close to 6mn m³/day of gas from Israel, which will gradually increase to about 15mn m³/day. But unless the global gas market situation changes, with its own gas production reduced, it remains to be seen whether Egypt will be taking increasing volumes of Israeli gas, beyond the minimum agreed take-or-pay volume.

Gas production from Zohr, Burullus, North Alexandria, and Baltim South West fields has already been reduced, with Egas also looking into reducing production of other gas fields – if needed – causing IOC’s concern.

With Europe planning to go green through its forthcoming Green Deal, impacting future demand for unabated gas, Egypt will need to look to Asian markets for future LNG exports, but even these are becoming highly competitive.

Remarkably, not only has Egypt not heeded the message, but it has not got through to Israel and Cyprus, who do not appear to be at all concerned with these developments, holding on to plans and projects that only made sense at a time of shortage.

Relying on the very low liquefaction cost of its LNG plants at Idku (Figure 4) and Damietta – expected to restart later this year – the Egyptian petroleum ministry’s response is a plan to sell LNG under renewable 12 to 18 month term agreements with a target price of $5/mn Btu, rather than on the spot market. But this is a risky and questionable approach, especially after allowing for shipping costs.

Eastern Mediterranean gas and LNG is too expensive to compete with gas further down the cost curve, such as Qatar, US and Russia and it will be facing headwinds now and in the future.

Unless they can be monetised soon, any future exports from the eastern Mediterranean region are likely to be limited and even then they must be low-priced – with profit margins largely eroded – to make any inroads in what is becoming a highly competitive market globally. Finding the gas appears to be the easy part.