Market barriers hamper EU hub liquidity [NGW Magazine]

The Dutch gas hub, the title transfer facility (TTF), has overtaken the UK national balancing point (NBP) as Europe’s most liquid hub in recent years. It saw 40,390 TWh traded in 2019, three times more than the NBP despite the latter’s head start, according to a recent report by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

The TTF also has the largest number of active participants – 167 versus the NBP’s 135 – and the highest churn rate, which stood at 97 in 2019 compared with the NBP’s rate of 14. The churn rate indicates how many times a contract changes hands before it goes to delivery. The TTF also has very good liquidity on the curve.

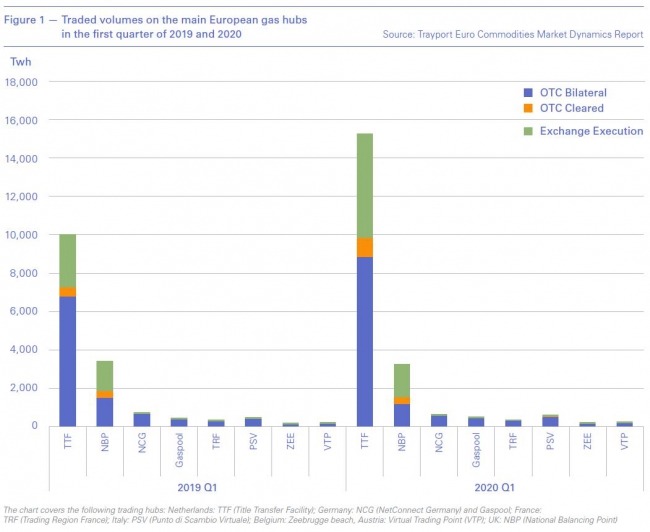

Volume growth on the TTF continued in the first quarter of 2020, with a year-on-year increase of 52% which means it had a market share of 74% based on all major hubs, according to the European Commission (EC)’s most recent gas market quarterly report. The euro-denominated TTF is also becoming a widely used benchmark in LNG contracts, even in some Asian contracts, the report noted.

Improvements have been noted at Europe’s less liquid hubs, such as Italy’s PSV where traded volumes have been steadily rising over the years. PSV is tipped to become a benchmark for southern Europe. Italy is well positioned in terms of LNG import capacity and pipeline imports from north Africa and soon also from offshore Azerbaijan when the 10bn m³/yr Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) is commissioned by the end of the year. Unlike Spain, for example, it also has good connections with central and western Europe.

The EC’s report noted that traded volumes on the PSV increased by a quarter year-on-year in Q1 2020, but that the hub only has a market share of 2.8% of all major hubs when ranked by traded volumes (Figure 1). Germany’s NCG and GPL hubs have also shown signs of better liquidity over the years even if traded volumes on these hubs declined year on year in the first quarter of 2020.

The EU’s Third Energy Package and subsequent network codes governing grid access have contributed to a more level playing field across Europe’s gas markets, with easier access to pipelines, storage and LNG terminals. Moreover, the EU Regulation on Energy Market Integrity and Transparency (Remit) has improved transparency for market players thanks to reporting obligations for production outages and flow data.

Not all are equal

Yet plenty of work remains to be done before more European hubs will reach maturity levels in line with the TTF and NBP. A recent study carried out by law firms Schoenherr, Philippe & Partners as well as Global Industrial Consult on behalf of the EC found that there are still many barriers to new entrants gaining access to European markets. This includes storage obligations, domestic market quotas, import/export licences, price caps and generally cumbersome administration procedures often in a national language. The study also noted that several countries require trading firms to set up a local office before they can enter the wholesale market in that country. This mainly applies to non-EU companies, and in the future possibly also to UK companies after Brexit.

The Czech Republic even requires local presence for companies that already have a base in other EU member states. This may be at odds with the EU principle of free movement of goods, the study noted. There are loopholes, however, as EU-based firms can apply for recognition of their local licence in order to trade gas in the Czech market.

Some countries also require audited business plans in the local language before granting market access. Excessive licensing requirements also include high financial guarantees, which is evident in Hungary, Poland and Romania. Traders see high collaterals as a significant barrier, and the study concluded they are a poor hedge against fraud and solvency risk as the check is only carried out by the national regulator once and only for new entrants.

“In general, high financial guarantees mainly deter new market entries, since they are no burden once the licence was granted,” the study said.

Polish storage obligations

Poland requires a separate licence for cross-border trading and the application must contain detailed information about business activities such as planned average daily imports. The trader, once licensed, is also subject to a mandatory storage obligation. The licensee must maintain reserves of gas equivalent to at least 30 days of average daily imports that can be delivered within a maximum period of 40 days. Moreover, traders are also obliged to diversify imports from abroad. The maximum share of imports from one source may not exceed 70% in the years until 2022 and no more than 33% in the years from 2023-2026. Many shippers have left the Polish market because of the storage obligations, the study noted.

However, the EC says the storage obligation is not compatible with the EU’s Security of Gas Supply Regulation and has warned that it may take the case to the EU Court of Justice. Poland should have responded by late February, but the case seems to have been delayed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Poland and Romania also enforce trading obligations. A licensed trader in Poland is obliged to trade no less than 55% of the gas injected into the system on exchanges and organised market platforms. Meanwhile, Romania has recently reformed its trading obligations which means that, between July 1, 2020 and December 31, 2022, producers with more than 3 TWh annual production have the obligation to offer 40% of their previous year's recorded gas production on centralised markets subject to the rules set by the National Energy Regulator (ANRE). This obligation applies to top producers such as Romgaz and OMV Petrom. Quotas are also in place for smaller players.

Price caps on wholesale markets are also a market barrier that has not been completely lifted. In early July, the EC sent a warning to Croatia over price caps which seemingly will be in place until March 2021. The EC noted that Croatia’s Gas Market Act adopted in 2018 had addressed many concerns regarding import and export restrictions and market liberalisation in general, but that this was not enough. Croatia’s role in the European gas market will be boosted significantly by the EU-backed 2.6bn m/year Krk LNG terminal which is expected to be commissioned early next year.

“The EC is of the view that such wholesale price regulation, even if limited in time, still does not comply with EU law,” the EC said.

Market barriers are not only restricted to eastern Europe. In July last year, the EC took Belgium to the European Court of Justice over its alleged failure to hand more power to its national gas and power regulator, Creg.

The EC is particularly concerned that Creg has not been granted the power to take binding decisions against gas and power companies for breaching market rules, but can only make proposals to the government. The Belgian government – and not the regulator – also sets the conditions for access to gas and power networks, which is at odds with EU law under the Third Energy Package. Moreover, Belgian energy law does not ensure that transmission system operators actually control the entire gas and power grids they are responsible for, meaning they may not be in a position to ensure non-discriminatory access to them.

The case was launched almost six years ago, in October 2014, when the EC sent the Belgian government a letter of formal notice. A decision by the ECJ is expected this autumn.

The EC is expected to propose new market rules for gas markets next year. This is an opportunity to address market barriers to trade, not at least because the gradual switch to renewable gases means many new and often smaller players are expected to enter the market in the coming years.