Majors adopt green targets [NGW Magazine]

In July, the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) announced plans to cut by 10% the average carbon intensity of their upstream oil and gas operations by 2025 compared with 2017, which may be extended to other sectors such as LNG in the future.

This is a very modest goal in comparison with the six biggest European oil companies – Shell, BP, Total, Eni, Equinor and Repsol – which have all declared some form of company-wide 2050 net-zero target over recent months, along with a raft of other emissions targets and proposals. The six are also members of the OGCI, but the goal will be collective, not individual minima.

The shift in focus in Europe is partly due to a severe anticipated policy response to climate change, along with growing public and investor concerns stirred up by increasingly severe climate model predictions. European industry bodies, shareholders and banks concerned about climate risk have been insisting that the companies work within the Paris Agreement climate goals (2 °C increase in global temperatures maximum). In addition, a large portion of Covid-19 recovery funds has been ear-marked to support decarbonisation in Europe, while lower anticipated oil and gas prices (and higher carbon prices) have made hydrocarbon projects less attractive.

Ambitious Europeans

Repsol was the first among the larger European oil and gas companies to commit to a global zero-carbon goal, which it did alongside Greece’s Energean in December 2019. Speaking at the time, Repsol CEO Josu Jon Imaz noted that technological advances and the use of carbon sinks would be important in reaching the goal, and indeed reliance on technological advances is a common feature of these long-term plans.

Overall, low-carbon projects are expected to account for around a quarter of Repsol’s capex over the next five years, and the company has underlined its commitment by seeking to link the targets to at least 40% of long-term variable pay among its senior managers.

Then in February, BP, under its new CEO Bernard Looney, announced a 2050 net-zero carbon emissions target that included scope three emissions – emitted by its customers from fuel it produces and sells – which is a far more ambitious goal than simply cutting emissions incurred in producing, processing and delivering the fuel (scope one and two). However, the target did not extend to the oil and gas that BP trades, processes and refines as a third party. The company also plans to reduce overall emissions intensity, where the CO2e/unit energy is reduced – and this does include emissions from the oil and gas it buys from others.

Observers point out that this can be lowered by producing and selling more clean energy alternatives, while the company’s own fossil fuel production and emissions continue to rise but at a slower rate.

BP’s move was followed by Eni in May, which took things a step further by committing to cut its absolute carbon emissions by 80% by 2050, rather than a net-zero target – although it does have a net-zero target for its upstream by 2030. Like BP, Eni’s goal includes scope three emissions, but it also includes emissions from third-party products going through its refineries or distribution operations.

In addition, Eni pledged to reduce its value chain emissions intensity by 55% by 2050. Analysts estimate that by 2050, this would mean oil would account for just 10% of Eni’s total sales, with gas at almost 65% and renewables at 25%. Eni said gas would reach 85% of total hydrocarbon production by 2050.

Shell announced its decision to go to net zero by 2050 on April 16. Other plans include a reduction in carbon intensity of 30% by 2035 and 65% by 2050 – the highest yet – and up from an earlier target of 50% by 2050 set in 2017.

Surprisingly, Equinor has so far only pledged a net zero absolute goal on its domestic Norwegian operations, rather than those globally. The company has set interim targets of 40% by 2030 and 70% by 2040. It also committed this year to cut life-cycle carbon emissions’ intensity from the use of all its energy products by at least 50% by 2050. Based on these targets, Equinor could see oil shrink to 15% of total sales, with gas at 45% and renewable energy at 40% by 2050.

On May 5 Total announced its own 2050 net-zero target, but it does not include scope three emissions from non-European customers and operations – despite being the biggest low carbon spender so far with 15% of capex going on such projects this year. Total has recently agreed to produce bitumen in India, which may be tough to decarbonise. The major is also targeting a 60% or more cut in the average carbon intensity of energy products used by its customers worldwide by 2050, with interim targets of a 15% cut by 2030 and 35% by 2040 – and has made the most progress so far, with a 6% decrease in scope three average carbon intensity since 2015.

How to get there

Early decarbonisation measures include reducing carbon intensity by limiting flaring and methane leakage, and powering offshore platforms with green energy from shore, such as Equinor’s Johan Sverdrup field. BP’s plans include installation of methane measurement at all its existing major oil and gas processing sites by 2023, followed by the reduction of methane intensity by 50%. Repsol also plans to reduce upstream methane emissions by 25% and halve flaring by 2025, removing it altogether by 2030.

Several companies have announced green power generation targets, which will reduce overall carbon intensity. Repsol plans to expand its low-carbon electricity generation capacity to 7.5 GW by 2025, up from almost 3 GW today. It has over 1mn power customers in Spain and wants to acquire 2.5mn by 2025. Eni is planning to expand its renewable electricity generation capacity to 55 GW by 2050, up from just 400 MW in 2020, 3 GW in 2023 and 15 GW in 2030, and is targeting over 20mn power and gas retail customers by 2050, up from 9mn now.

Equinor aims to increase renewable generation capacity to 16 GW by 2035, with an interim goal of 4-6 GW by 2026 – again, a sharp increase from 500 MW at the end of 2019, with renewable spending set to rise to $1bn/yr out of a total investment of $10-11bn in 2020/21, to $3bn/yr in 2022/23.

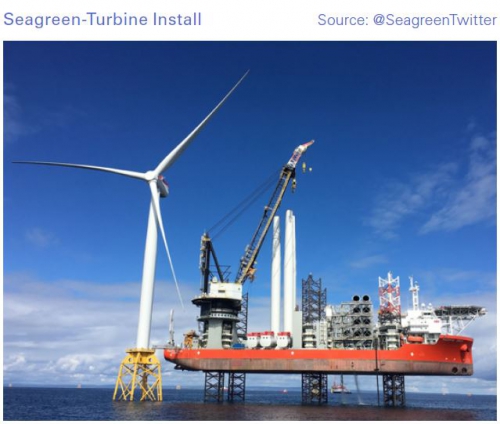

Total wants to increase the share of energy it sells as electricity, including a rise in its renewable generation capacity to 25 GW by 2025; spending over 10% of its capex, rising to 20% by 2030 or sooner. Despite steep cuts to overall spending, it plans to invest $1.5-2.0bn in 2020, with recent deals including a stake in the UK’s SeaGreen offshore wind project.

However, Total also sees gas to power as an important element in its carbon reduction plans alongside renewables, and is pushing forward with major LNG expansions, including the greenfield 13mn metric tons/yr Mozambique LNG project. Like Total, Shell is also bullish about a combination of gas and renewables. It has declared its intention to be the world’s biggest power company by 2035.

Companies are also developing zero-carbon products – for example, Shell’s carbon-neutral LNG (using offsets), which it has sold to customers in east Asia.

To further reduce emissions, options then become more costly, and there may be pressure to sell assets if mitigation costs become too high. Carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) can be used to lock up scope three (and 1+2) emissions centrally, from a power station or hydrogen production facility (using methane feedstock), but remains expensive and little used so far. However, it is a key part of the EU and UK’s zero-carbon vision, and presents a clear opportunity to maintain long term gas operations.

Projects are now beginning to move forward, with Equinor and partners Shell and Total taking a final investment decision in May on the $680mn, 1.5mn mt/yr Northern Lights project off Norway. Equinor is also leading the H2H Saltend hydrogen and CCS project in northern England that will use gas as feedstock – lengthening the life of its offshore production and pushing back stranded asset dates. Eni is considering its first CCS project in northeast Italy to capture emissions from gas-fired power plants and industry.

Investing in the supply of low-carbon gases, power and infrastructure should provide growth opportunities, although value pools of the sort oil companies had been used to remain elusive. Repsol, BP and Eni are completely reorganising their corporate structure in order to more effectively manage the transition.

The OGCI comprises: BP, Chevron, CNPC, Eni, Equinor, ExxonMobil, Occidental Petroleum, Petrobras, Repsol, Saudi Aramco, Shell and Total. NGW understands that for the purposes of measuring their success in hitting the target, member companies report their own data to an independent third party, EY, which will anonymise the data before circulation.

The progress towards the target will be reported transparently on an annual basis consistent with OGCI public reporting rules, methodology and assumptions, and reviewed by EY.