[NGW Magazine] Bolivia's Upstream Lurches into Gear

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 16

By Sophie Davies

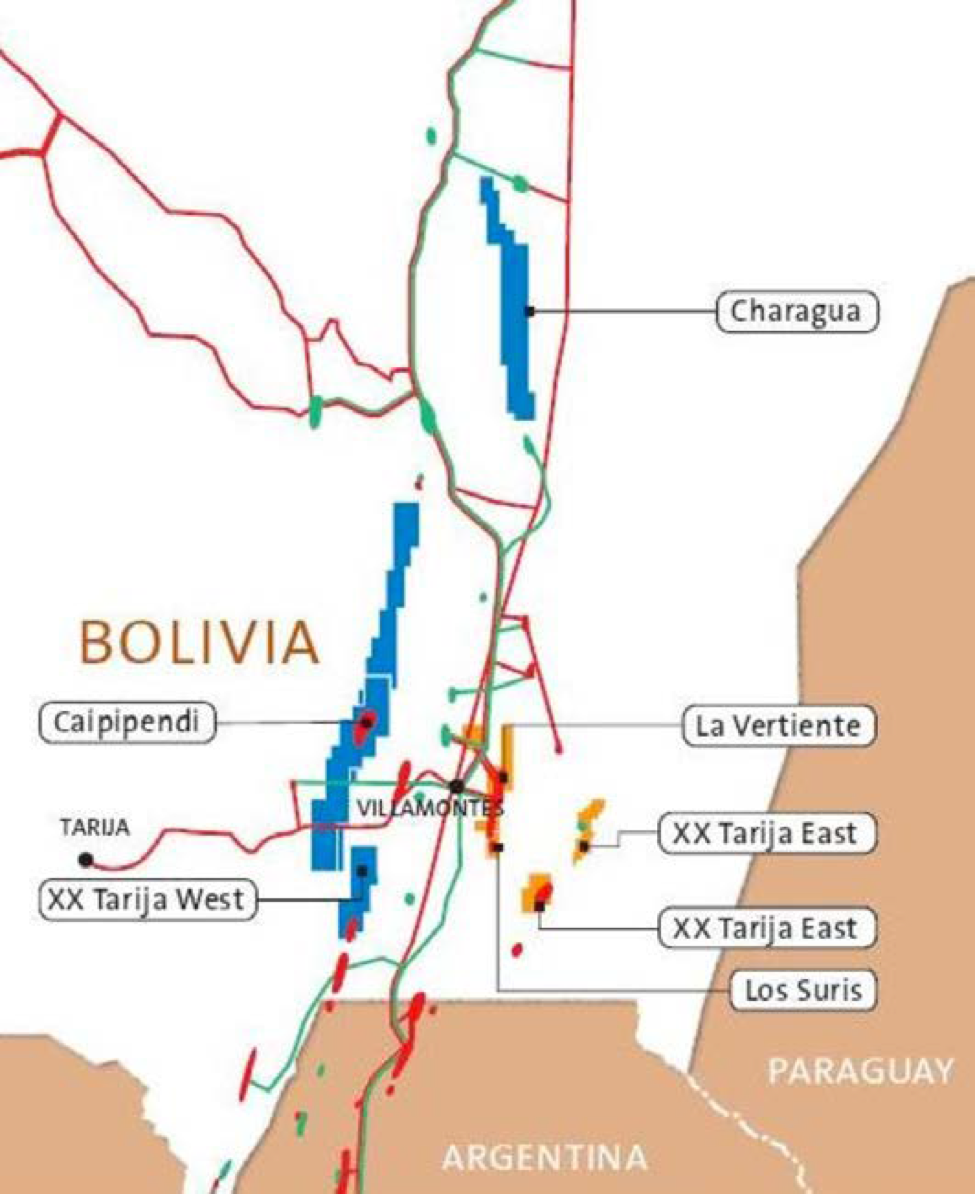

Exploration is set to begin at the Charagua gas block in Bolivia in September, giving a much-needed boost to Bolivia’s E&P sector. But experts warn that overall progress is still slow.Bolivia’s state-run oil and gas company YPFB and its Argentine counterpoint YPF announced that they will launch exploration at the Charagua block and that investment could reach $1.18bn.

In January, the two firms inked a contract to jointly explore and drill in the east Bolivian province of Santa Cruz, where Charagua is. The two firms subsequently formed a joint venture to develop the project, in which YPFB has a 51% stake.

The Charagua block, which covers an area of 99,250 ha, is believed to hold an estimated 2.7 trillion ft³ of natural gas. It is thought to have a daily output of 10.2mn m³ of gas. Over its lifetime, the block is expected to provide additional revenue of $12.36bn for the Bolivian government, which relies heavily on oil and gas earnings and has been hit hard by the low oil prices of recent years.

Almost a twelfth of Bolivia’s GDP comes from hydrocarbons and a thid of domestic investment is derived from hydrocarbons-based revenue. In addition, more than half Bolivia's exports are hydrocarbons. The start of exploration at the block “is definitely a positive sign and hopefully it will mark the start of a more active period in terms of E&P,” Katie Micklethwaite, senior Latin America analyst at the consultancy Verisk Maplecroft, told NGW.

However, progress at the block is not necessarily reflective of there being a general improvement in Bolivian E&P as yet, she cautioned. “The start of exploration activity in Charagua is something of an outlier,” she said. “We are not really seeing a lot of movement on the E&P front despite the government’s theoretical commitment to stepping it up. In fact, we have seen a bit of concern recently from industry sources and the media that not enough is being done to increase reserves or start producing in new areas,” she added.

Among those companies showing the most interest in Bolivia’s upstream sector are Shell, Repsol and Gazprom, which have already invested in it, Micklethwaite said. “What we’re not seeing is a lot of interest from new players, such as Chinese companies,” she added.

The Bolivian government has been talking for several years now about the need to boost activity in the sector, which faces a number of challenges including bureaucratic red tape causing contractual delays and unrest among local communities. Earlier this year, YPFB said it planned to move forward with exploration activities at 18 oil and natural gas wells this year, as part of a $692mn exploration programme.

The firm, which is under pressure to find new sources of oil and gas because of the country’s depleting existing reserves, has ploughed millions of dollars into exploration in recent years. That level of investment looks set to continue, with La Paz saying it will invest $12.7bn in oil and gas projects over the next five years.

Yet last year the firm did not make any commercial discoveries and – if gas consumption continues at the current rate – the country’s gas reserves are expected to be exhausted within less than a decade. The country’s energy ministry has also indicated that the government will pass new legislation this year intended to overhaul the oil and gas sector. This will cover contract terms, exploration in protected areas, incentives, compensation, and prior consultation mechanisms, but so far this is just theoretical as no new laws have been enacted.

Companies have been deterred from entering into Bolivian E&P in the past due to complications over drilling in protected areas, and this looks set to continue, said Micklethwaite. “Although the government is very keen to increase oil and gas exploration and production, not everybody in Bolivia is in agreement, and there are particular concerns about the prospect of the industry expanding into sensitive areas such as the Tipnis national park,” she said.

Tipnis is a biodiversity hotspot in Bolivia and there has been a lot of controversy in recent years of whether to allow upstream oil and gas activity there, even though a controversial road was laid across it. Total and Petrobras started exploring there a few years ago.

If a project does not have the support of local Bolivian communities, there can be “significant operational, security and reputational consequences for those connected to it,” she added. Another area of uncertainty revolves around the future of Bolivia’s gas export market, Micklethwaite noted.

Bolivia in the past has exported almost 70% of the gas it produces to neighbouring Brazil and Argentina. However with both Argentina and Brazil developing their domestic hydrocarbons potential “that demand might not be there for ever,” she warned. “If one or both countries decide to cancel or scale back their contracts with Bolivia, it’s hard to see where else the country will be able to sell its gas. Most of Bolivia’s neighbours produce their own oil and gas or they have 'thorny' relations with Bolivia, such as Chile," she said.

Chile and Bolivia have a territorial dispute going back over a century, concerning Bolivia's 'right' to a Pacific outlet. Bolivia used to own a section of Pacific coastline but lost it to Chile in the War of the Pacific in the 1880s. In the early 1990s the Bolivian government proposed building a pipeline through Chile to the Pacific port of Mejillones so it could export its gas and relations have been strained since Chile's refusal.

Fears have mounted in recent months over whether Brazilian demand for Bolivian gas may begin to wane, after officials said that Brazil could require less imported gas from its neighbour in future as output from its offshore fields rises. There are also concerns that YPFB’s current gas export contract with Brazil, which is set to be renewed in 2019, will be weaker than the current one.

Research consultancy Wood Mackenzie – also part of Verisk – has said that the post-2019 contract could have lower minimum take-or-pay volumes. If Brazilian demand does wane, other options for Bolivian exports do exist, though they are limited. Paraguay has been touted as a possible buyer of future Bolivian gas supplies.

Nonetheless demand from Paraguay would be modest and diplomatic relations between Paraguay and Bolivia are fairly strained. What’s more, it is a very early-stage plan that may not come to fruition. It is clear that much uncertainty still exists in Bolivia’s energy sector – and gas reserves still need to be boosted – but the progress at Charagua is a step in the right direction.