[NGW Magazine] Europe Riven by Nord Stream 2

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 20

By William Powell

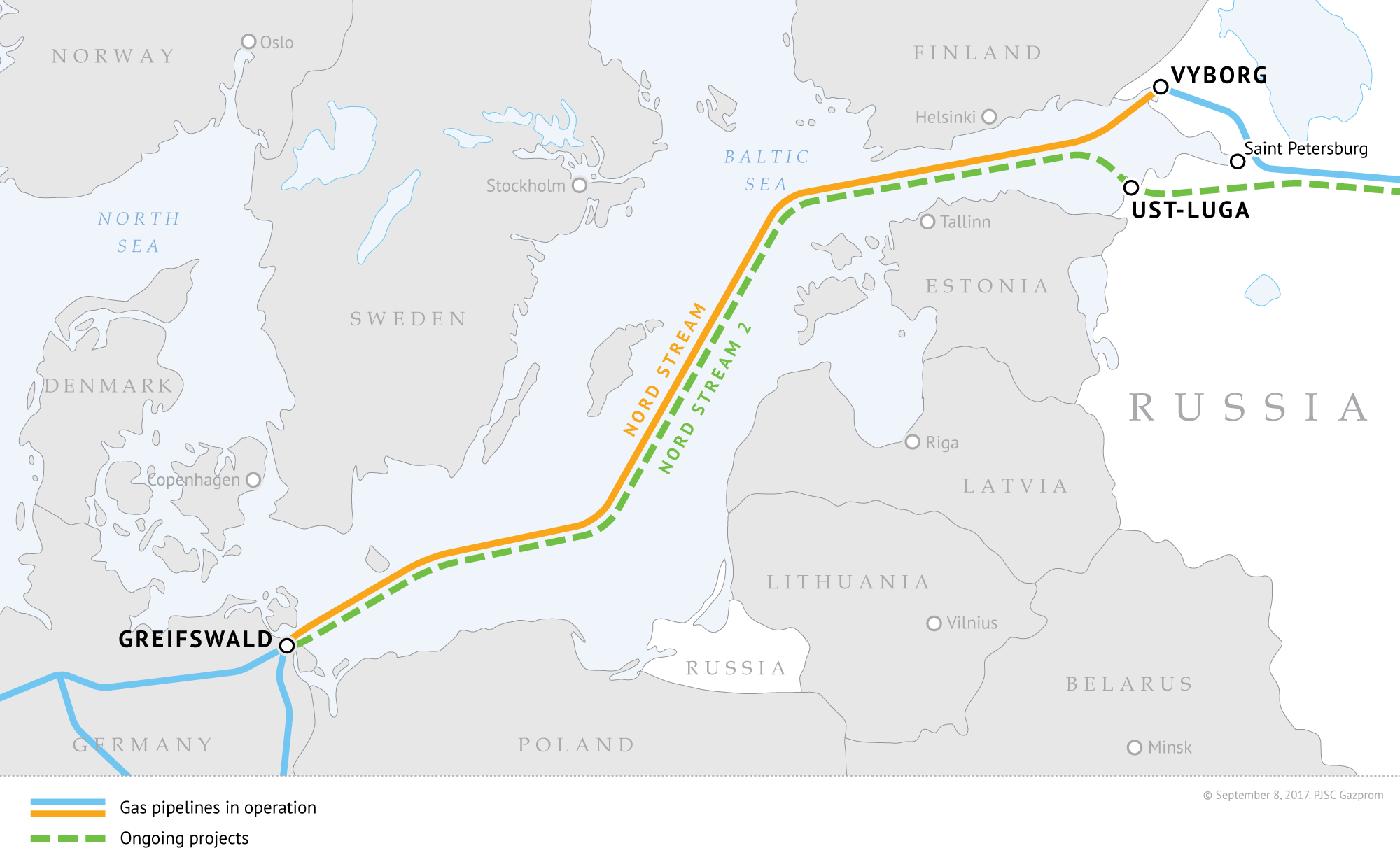

Is this the world’s most controversial pipeline project ever? Its sponsors say it is needed for Europe’s supplies, but its opponents are raising a wide range of objections.

The European Commission (EC) late in September lost its fight for a negotiating mandate to impose conditions on the Russian-backed, privately-financed 55bn m³/yr Nord Stream 2 project. The legal opinion submitted to the European Council said there were no grounds for a mandate (see below).

And hubs are becoming more liquid further east. Their ability to set prices that are based on gas supply and demand means that Gazprom is now a price-taker in Europe, competing with others for market share.

But the EC is not happy about the anti-competitive lack of third-party access to NS2. It told NGW that it would "continue to follow the discussion in the Council very closely following their analysis and study the opinion by their legal service."

The president of the EC, Jean-Claude Juncker, in his State of the European Union speech in September, spoke of the follow-up "to the solidarity aspect of the Energy Union, including a proposal on common rules for gas pipelines entering the European internal gas market; and swift implementation of the Projects of Common Interest necessary for the connection of the European energy markets."

Image credit: Gazprom

The EC could retrospectively amend the 2009 Third Energy Package to extend third-party access to offshore pipelines, to be redefined as interconnectors – although this would be formalistic without further change within Russia itself (see below).

This could be done by Christmas, delegates and speakers at the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies heard at the Gas Day October 12 which was held under the Chatham House rule. This would need only a qualified majority of member states' approval in order to become law. It would also be applied to other infrastructure bringing gas to Europe.

Depending on the approach, this might not do the EU’s reputation as a rules-based region any good in some circles, as it mixes politics with law too freely. It sends mixed signals to investors if one pipeline – Nord Stream 1 – is fine but another, identical in almost every respect, is not. People would be entitled to ask what goes on behind the closed doors of the member states, delegates heard.

Stark differences of opinion over what NS2 will do to Europe’s gas market still exist between Poland and some other former Soviet satellites or republics on one hand, and Germany and other western European countries on the other; and the arguments over whether it should be allowed to be built, and about how much of the onshore line, Opal, should be used, could be seen as symptoms of unresolved, older conflicts between the two sides.

Perhaps unconsciously aiding the EC is Denmark. It is considering amending its law on the continental shelf, to insist that NS2 does not enter its territory even though the first, 55bn m³/yr line, does. The government is justifying the draft on grounds of foreign policy, defence and security objectives, but the state has had the paperwork from Nord Stream regarding the use of its territorial waters since March 2016 – a full two years after the EU and US imposed sanctions on Russia following its recognition of Crimea as Russian territory.

If Danish parliament does vote to force the pipeline north of its territory, there would be additional costs incurred as the longer line would be laid in busier shipping lanes and over an as-yet uncleared seabed littered with possibly still active military debris; and also there could be damages payable to Allseas, which has been contracted to lay the pipeline. The cancellation of South Stream, where Gazprom had to pay Saipem damages, is a precedent.

As it is now almost winter, little can be done in the rough waters until spring: the opportunity of starting in summer has been lost, although Gazprom maintains that everything is on schedule.

Nord Stream AG did not comment on the length of the delay, saying it was prepared for the northern route; but some sources think it would add a couple of years to the construction process: first gas in the summer of 2021.

This would incidentally be good news possibly for Ukraine’s gas transmission business, although speakers also warned of the uncertainties surrounding the rule of law there too. Tariffs could be arbitrarily hiked to plug budget gaps, even though its pledged adoption of EU network codes should make it adhere to the charging methodology.

That would mean not working out the yearly cost of maintaining the system and apportioning it equally to each molecule, but selling capacity though competitive auctions. It was noted at the Gas Day that while transmission system operators (TSOs) had grumbled about short-term capacity bookings that the network codes encourage, the vast majority of EU pipelines are fully amortised, so the owners only need to cover their operational expenses. Ukraine's pipes are as old as most, with a $3bn maintenance plan still in abeyance.

Rule of law

The draft law has been attacked in the Danish press as being wholly against the rule of law and would make mockery of Danish democracy, a leader in the Jyllands Posten said October 13. And there is also the question of timeliness: with a tenth of the pipelines already coated for laying on the cleared Baltic seabed, parallel with Nord Stream 1, changing the terms and conditions now on purely political grounds would go against the rule-based system that the European Union prides itself on. It could also violate rules that protect investments, such as the Energy Charter, which Denmark – but not Russia – has ratified. After all, Nord Stream 1 has been operating without any problems at all so far, if viewed purely as a pipeline.

Russia could choose to remove the problems if it ended Gazprom’s pipeline export monopoly, so that Novatek or Rosneft could export gas through existing or new pipelines, but that is not on the cards.

Gazprom is fighting to maintain sales at home as efficiency measures and industrial decay kill off demand. It is trying every way it can to boost demand for its production, so needs all the state support it can get. Nor does Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, want to see it weakened, with Russian gas competing with itself in an oversupplied EU market. Delegates heard that the monopoly structure would most probably stay in place, unless Gazprom seriously under-performed.

Faced with all the management time that is still to be spent defending NS2, it would not be surprising if some of the consortium – French Engie, German BASF and Uniper, Austrian OMV and Anglo-Dutch major Shell, which this summer had to justify NS2 to the Danish Energy Agency – decided that the game was no longer worth the candle, although so far none is wavering in support of it.

And the decision by three gas pipeline operators – Belgian Fluxys, Dutch Gasunie and German Ontras – to each take a 16.5% share in Eugal, the onshore section of NS2 running parallel initially to Opal, suggests that they are ready for NS2. Eugal operator Gascade, now left with 50.5%, said October 19 that work is fully on schedule and it aims to complete Eugal's first string as early as the end of 2019. It will have two pipes, each of 1.4 metres diameter, and a combined maximum capacity of 51bn m³/yr.

Russian gas release

One solution to satisfy Europe would be to introduce a gas release programme using the St Petersburg commodity exchange (Spimex): it would show that Gazprom was adjusting to the competitive world it is aiming its gas at.

With 37% of European demand already under its belt, the company could however afford to show a change of direction towards competition; while the Kremlin could also achieve a goal – which it failed to do with oil – of creating a price-setting index at Spimex.

A gas release programme would allow other firms the right to buy gas at Spimex for delivery through NS2. This would represent only a minor loss of control for Gazprom, some speakers argued; and it would be a face-saving way out as well as protecting Gazprom from further anti-competitive probes in Europe itself. "It would be relatively easy to allow some gas release programme at Spimex; the quasi-TPA aspect of NS2 would not pose any real threat, it would mean losing a tiny amount of control," a speaker said.

This would also mean a radical change in the way gas is traded on the exchange, with ramifications for greater efficiency at home: at the moment, not only is Gazprom the biggest seller of a relatively small volume (16bn m³), accounting last year for two thirds of the transactions; there were also no resales going on between the buyers; and the trades were all short term, not forwards.

And finally, of the buyers, almost half (40%) last year were subsidiaries of Gazprom. In other words, there is the possibility at least that their function is at least partly to keep gas prices up. So a release programme would change that balance slightly.

But this is a sensitive area for Gazprom, whose power in Europe depends partly on its capacity in pipelines. It does not want to end up like Turkmenistan, selling all its gas at the border, be it at Vyborg where Nord Stream 1 enters the Baltic Sea; or on the Russia-Ukraine border.

There is also country risk associated with buying gas and shipping it through Ukraine: gas has gone missing in the past.

Legal opinion defeats mandate

The legal service of the Council of the European Union told it in a restricted document dated September 27 that its request for a legal mandate to negotiate the gas pipeline's terms with the Russian Federation was not legally sustainable.

EU vice-president for the energy union, Maros Sefcovic, had surprised the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, when he announced in June that he would appeal for a negotiating mandate to determine the legal position of Nord Stream 2. She said that existing legislation was enough. The mandate could have allowed opponents of Nord Stream 2 to impose conditions on Gazprom's use of the line. But this is no longer an option.

For example, the legal service flatly denied one of the arguments for a mandate, namely that Nord Stream 2 would be operating in a legal void. It also ruled that the EU cannot determine the import route for gas to a member state – in this case Germany. It said the provisions of the draft mandate must not amount to structurally regulating the gas supply of one or several member states from a third country, including via choices of supply routes.

Further it said the EC had failed to demonstrate a link between the operation of NS2 and any substantiated market or security concern for energy supply into the EU as alternative routes with augmented capacity will only increase the EU's external supply networks.

It said that the assumption that the opening of supplementary routes or capacities might increase the EU's dependence on its external energy providers is, at the very least, counter intuitive and said it was not the case that the limited jurisdiction of the EU and its member states, on the one hand, and a third country, on the other hand, would lead to a legal void.

The legal service argued that there are no third-party entry or exit points and so the line falls either under Russian or EU jurisdiction at any point, depending on which territory it is in. The pipeline would in any event be subject to the relevant rules of international law, and that there cannot be a conflict of laws, contrary to what the EC claims.

The legal service said that notions of a legal void and a conflict of laws that the EC had proposed in support of the need for the envisaged agreement did not mean that there was necessarily a legal need to negotiate it. These were political arguments, it said. The EC’s draft mandate does not and cannot aim at precluding the construction or opening of the pipeline.

The first Nord Stream gas pipeline became operational five years ago, with 55bn m³/yr of nameplate capacity. Between October 8, 2012 and October 7, 2017, the pipeline transported 182.1bn m³, Nord Stream reported October 17. According to the company, since the beginning of the work the system has successfully increased the volumes of supplies. In 2014, it worked with 65% nominal capacity, which rose to 71% and 80% in 2015 and 2016, while it is projected to reach 90% in 2017.