[NGW Magazine]: Opening up Sardinia to a World of Gas

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 17

By Mark Smedley

Sardinia is opening up to natural gas. But forget any past notions of a new pipeline from Algeria, or even one from mainland Italy: quick and easy LNG is the way ahead.

Sardinia's gasification (‘metanizzazione’) will be based on a network of small-scale LNG terminals, interlinked by a backbone of pipelines, and open up to cargoes from anywhere in the world.

Indeed it offers a template for how cleaner-burning natural gas could improve the economy and environment of islands elsewhere in the Mediterranean, or indeed anywhere, avoiding costly long-distance pipelines.

Much of the LNG brought to Sardinia will be consumed in the port areas: regasified for use by industry there, or else supplied direct to the growing bunkering market. Forecasts suggest that by 2030 up to a fifth of LNG supplied to Sardinia will be consumed as ships’ fuel, an important factor not only for fleet operators but also holidaying Qatari and Russian billionaires with luxury yachts.

Sardinia, the second largest island in both the Mediterranean and Italy, relies on tourism but also has industrial complexes in the south yet a sparse population density inland. It has just 1.7mn people, compared to 5mn who live on larger Sicily, Italy's other big island, also industrialised but which has received gas since Eni opened the TransMed pipeline for Algerian imports to Italy in 1983.

Sardinia is still waiting, 25 years on, for its natural gas. But that is about to change.

A pact was signed July 2016 between then Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi and Sardinian regional president Francesco Pigliaru to step up infrastructure investments, including the gasification of the island, and building a backbone gas transport pipe. Italy’s economy ministry has held several meetings with the region and operators and Sardinia features in the Italian government’s national energy strategy (SEN), published June 2017, with an eight-page annex devoted to the island’s planned gasification.

The first such small LNG terminal, HiGas, near the west coast town of Oristano, was fully approved this January though is not yet under construction. Other projects are also being permitted, including ones by Cagliari-based IsGas and Eni.

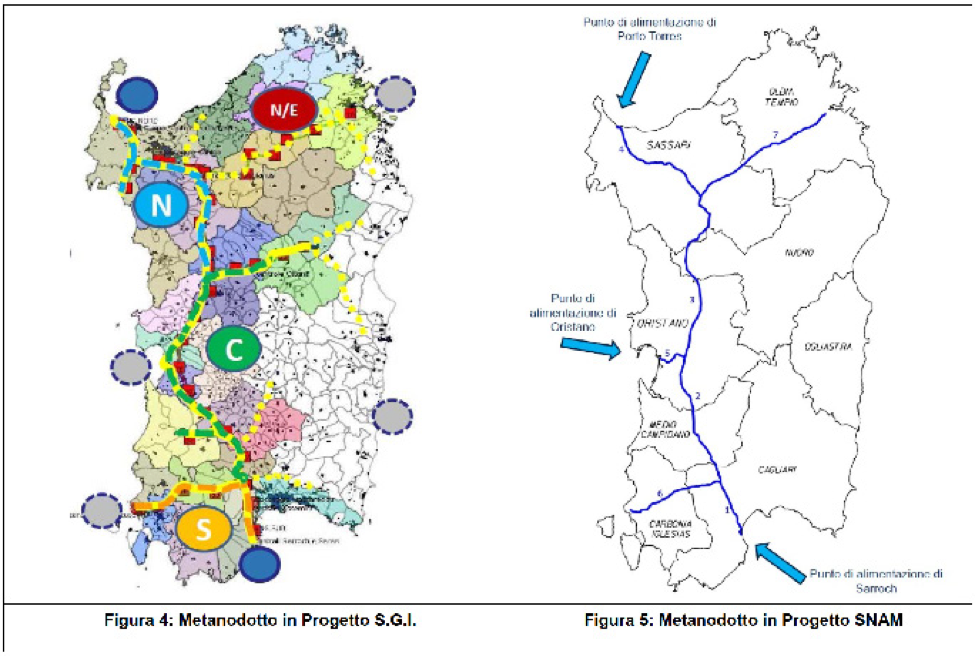

Italian mainland gas grid operator Snam has submitted its environmental impact assessment for a 600-km network of pipes on the island (400 km being a ‘backbone’ north-south pipeline), which has been reviewed by the Sardinian regional government, and sent to the national environment ministry in Rome for approval.

Snam thinks this could be built and enter service as soon as 2019-20. A similar 600-km proposal had been made by Australia’s Macquarie-run distributor Societa Gasdotti Italia (SGI), which means both governments and the national regulatory authority (AEEGSI) now have competing proposals to evaluate.

Much of the preparation for Sardinia’s opening to natural gas stems from a detailed 392-page academic study published August 2016 by the regional government: Energy and Environmental Plan for the Sardinia Region (Pears). This cites an IEA forecast that shale gas production globally could triple by 2035 to justify its forecast that ample cheap LNG supplies will remain available to places like Sardinia. That confidence is partly echoed by the Italian national energy strategy (SEN) which says that Sardinia's gasification "benefit from a window of competitive LNG prices in decline out to 2024-25."

Sardinia could absorb 0.5 to 1bn m³/yr by 2030

This forecasts the island’s natural gas requirements by 2030 at between 0.535bn m³/yr (base scenario) and 0.96bn m³/yr (based on intensive development). It also presents a development scenario of 0.794bn m³/yr, based on modest development.

With the base 2030 scenario, it expects 51% of use to be in heating and industry, 26% in power generation, and 23% in transport. But gas use in transport increases in line with development. Hence, for ‘modest development’, the ratios are 44%, 34% and 22%, while for intensive development, they are 46%, 30% and 24%, the last figure being transport.

Although nearly 1bn m³/yr may not sound large, it equates to Luxembourg’s current gas use and represents more than 1% of Italy’s roughly 70bn m³/yr consumption in 2016.

Galsi no longer an option

Piped Algerian gas was once seen as indispensable to Sardinia’s gas plans. A project company, including Sonatrach, Enel, EDF-owned Edison, Hera, German firm Wintershall and the Sardinian authorities, was set up in 2003 and in 2005 a feasibility study for a 8bn m³/yr pipe called Galsi – subsea from Algeria, crossing Sardinia from south to north, then subsea again to the Italian region of Tuscany – was completed, followed by an intergovernmental agreement between Italy and Algeria in 2007, with plans for its completion by 2014.

Nothing then happened – apart from Wintershall’s exit from the project, Algeria’s declining gas export capability, and the huge drop in EU and Italian gas demand from 2010 – until in May 2014 the Sardinian government decided that Galsi had definitively stalled and officially sought other options.

Italy’s national energy strategy, published mid-2017, further notes that there is “uncertainty over the renegotiation of possible [Algerian] supply contracts through Transmed which will expire 2019.”

The document noted that a gas pipeline from mainland Italy (Tuscany) is technically an option but adds that “gasification through small scale LNG... appears the preferred solution.”

Handful of LNG facilities discussed

In western Sardinia, according to the strategy document, Italy’s economy ministry (MISE) has begun the authorisation procedure for three distinct small-scale LNG facilities – each with storage for some 10,000 m³ LNG – to be built in the Oristano area. One is by HiGas (a joint venture of Italian firms Gas & Heat, and Concordia); one is by EDF’s Edison; and the third is by developer IVI Petrolifera.

Each would unload LNG from carriers, store, and also reload it on to smaller cryogenic distribution carriers for the industrial, town gas, and transport sectors. HiGas is fully authorised – though apparently has yet to begin construction – while the other two are still pending permits.

It's worth mentioning that one of HiGas's investors, Concordia, owns Grecanica Gas which installed a natural gas distribution network to ten remote districts on the southern tip of Calabria, the southernmost region of mainland Italy, at a cost of €45mn.

In southern Sardinia, a further small-scale LNG project has been proposed by IsGas (IS Gas Energit Multi-Utilities) which already operates an existing piped propane distribution network in Sardinia’s regional capital Cagliari. This project foresees building the 20,000 m³ of LNG tankspace at the port there, connected to a 100,000 m³/hr (0.88bn m³/yr) regasification unit.

Sources tell NGW that full capacity of 0.88bn m³/yr could be achieved if eight small LNG cargoes are discharged per month. The EIA either has been presented, or soon will be, to the environment ministry in Rome – following a preliminary assessment by Cagliari Port Authority.

And in northwest Sardinia, Eni has proposed a permanently-moored LNG storage vessel at Porto Torres, in conjunction with an industrial consortium in the nearby city/province of Sassari. A small-scale LNG scheme, if realised, could provide natural gas to several existing local distribution (LPG) networks, and those planned or under construction.

The role of LPG

Sardinia also has 2,000 km of pipe distribution networks, serving 60,000 customers, of which 60% supplying propane and 40% other liquid petroleum gases (LPGs), according to data from regulator AEEGSI republished in the mid-2017 strategy document.

These moreover deliver 16mn m³/yr and serve 98 municipalities, or more than a quarter of Sardinia’s total. There are also plans for this network to be almost doubled to 3,800 km at a cost of €550mn – of which €130mn is already invested – with half of the capex subsidised by EU, national or regional grants. Their conversion to natural gas would be relatively simple; indeed Spain – where Macquarie is already active as a gas distributor – has ample experience of doing this.

Macquarie though has attracted recent criticism for its past use of debt leveraging at a UK utility that it owned which ran counter to conditions set by the relevant British regulator and which added to customer bills.

Given the extensive nature of Sardinia’s LPG/propane distribution networks, it would seem natural to interconnect them – and this is precisely what the rival schemes of Macquarie-run SGI and Italy’s Snam propose.

SGI -- which owns a formerly Edison-owned network in mainland Italy of 1,550 km and which since 2016 is jointly owned by Macquarie and Swiss Life – presented in its latest two ten-year plans a project for a 400-km backbone 26-in pipe, plus 200 km of 6 to 12-in diameter pipes to the island’s main industrial bases including Cagliari, Sulcis, Sassari, and later Olbia in northeast Sardinia.

The EIA for the first phase of a ‘central-south’ pipe (from Oristano on the west coast, via Cagliari in the south, to Sulcis in the southwest) was recently filed to both Rome and Sardinian authorities. SGI also presented it to public meetings in mid-May in Oristano and the southwest city of Carbonia.

Snam has also submitted a proposal for a 390-km backbone pipeline, of 26 in and 16 in diamters, plus some 200 km of regional distribution pipes, of 16-in and 6-in diameters. It too submitted the EIA to the regional government in May and has since informed NGW that this has since progressed, in August, to the Italian environment ministry.

LNG bunkering

In addition to the hard slog of converting tens of Sardinia's local LPG distribution systems to natural gas, the developers of small LNG facilities are keenly aware of easier markets to tap, and not just energy intensive industries in the larger towns.

By January 1 2020, the whole world’s shipping must comply with a new UN International Maritime Organisation cap of 0.1% sulphur content in marine fuels. In most of the Mediterranean, the cap today is 3.5%, which means that the air can get quite unhealthy when several large ships are in port.

As there are just three ways of complying with the new tighter cap – installing expensive pollutant-removing scrubbers onboard; using ultra-low sulphur diesel; or switching over to LNG – it is expected that a lot of shipping in the Mediterranean will need new refuelling points for LNG bunkering.

The pressure will not just come from the IMO. Air quality improvement programmes are expected to be rolled out in port areas such as Cagliari, Porto Torres and Olbia, which should prod not only shipowners but also the island’s coal and oil-fired power plant owners towards uptake of natural gas.