LNG to Fuel Majors' Emissions Growth: WoodMac

Carbon emissions from fields owned by 25 oil and gas ‘majors’ are forecast to increase by 17% in the ten years to 2025, against only a 15% rise in their production, said global consultancy Wood Mackenzie on September 20.

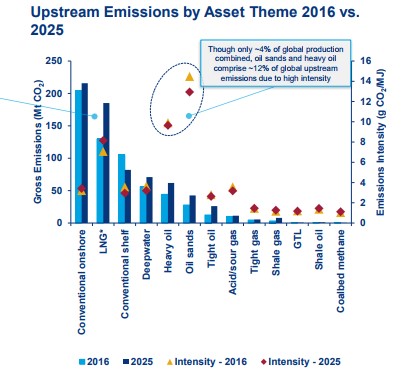

LNG, heavy oil, and oil sands will drive emissions growth, as they have higher emission intensities, it added.

It sees LNG emissions among the 25 companies increasing from about 130 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) in 2016 to about 180mn mt in 2025. It explains that LNG emissions include both those from upstream supply fields and liquefaction plants.

The 25 are not named in the report, entitled ‘Upstream Carbon Emissions Performance and Risk’. However, all are believed to be investing in a substantial increase in global liquefaction capacity during the 2016-25 period under review.

“LNG emissions are forecast to realise the largest – and fastest – absolute increase, with liquefaction emissions also growing at the fastest rate of all the sources, about 43% versus 22% production growth,” said the study’s co-author Amy Bowe.

Carbon intensity of LNG (indicated as red squares and yellow triangles in the graphic, far below) exceeds that of both tight and shale gas – something not always appreciated by campaigners against shale gas in Europe, which imports LNG.

Full-cycle LNG is more benign

But the report’s executive summary does not include expected carbon savings further downstream, where LNG displaces oil and coal in consumer markets. WoodMac has indicated that, on a full-cycle carbon intensity basis, LNG is still far more favorable than coal -- though less than pipeline gas.

Liquefaction plants are certainly energy-intensive, with typically 10% of gross gas used in the LNG value chain used to liquefy it to minus 161o Celsius, and a further 5% used to ship LNG to markets, meaning that only about 85% of the wellhead production is delivered net to consumer markets.

Very few LNG export projects worldwide have incorporated carbon capture and storage (CCS), in order to mitigate CO2 emissions to the atmosphere, and they are expensive. Statoil included CCS at its Snohvit LNG venture in Arctic Norway, while Western Australia government made it a condition that Gorgon LNG, at $54bn the world's most expensive liquefaction and export project built, include a $2bn CCS unit that strips out CO2 from feed gas.

“Under a $40 per tonne carbon dioxide cost – which we believe represents a realistic average – the value of companies’ [total] upstream assets could be reduced by up to 7%, depending on the regulatory regime,” said Bowe: “However we expect this will actually be closer to 2% under the most likely fiscal and regulatory scenario.”

Upstream emissions by asset theme (Graphic credit: Wood Mackenzie)

Mark Smedley