LNG plan for Guinea to fuel alumina exports [Gas in Transition]

In September 2021, Colonel Mamady Doumbouya staged a coup in the West African country Guinea which overthrew the country’s elected president Alpha Condé. Condé had been re-elected for a third term in 2020 after pushing through constitutional changes which overcame a two-term limit. The elections were marred by violent protest.

Doumbouya announced in 2022 that there would be a three-year transition period before a return to civilian rule. In February this year, Doumbouya dissolved the government by presidential decree and ordered the security forces to seal the country’s borders.

A new government was set up in March after ECOWAS – the Economic Community of West African States – lifted economic sanctions on the country imposed as a result of the 2021 coup. Doumbouya has promised a referendum on a new constitution by the end of this year.

West Africa LNG project

In April, the transitional government approved an agreement between the government and West Africa LNG Group for the construction of a large-scale LNG import terminal at the port of Kamsar. The agreement was for work to start no later than three years after final approval of the decision by Doumbouya.

West Africa LNG is a special purpose entity established by Baton Rouge-based, Louisiana company AfricaGlobal Schaffer (AfGS). West Africa LNG says its mission is “to improve the lives of the Guinean people by transforming the country’s industrial, mining, agricultural and residential sectors through the provision of commercial quantities of affordable and environmentally friendly LNG.”

The LNG terminal will supply gas to end users either by pipeline or via small-scale LNG distribution using cryogenic trailers or ISO tanks.

However, the project goes beyond just an LNG import terminal. In a second phase, West Africa LNG plans a liquefaction plant on the same site after “potential Guinean offshore gas wells are developed and connected to the mainland via a pipeline.”

This second phase of the project is distinctly speculative. Only three offshore exploration wells have been drilled in Guinean waters. None found commercially viable quantities of oil or gas. Although the West African coast is prospective, little is really known about the country’s oil and gas potential.

It’s all about alumina

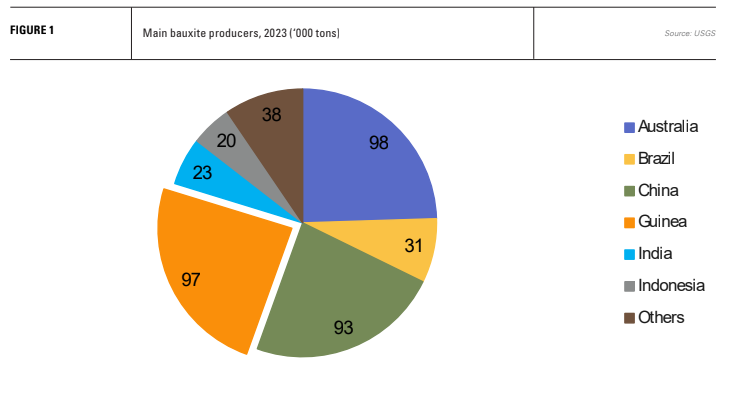

Bauxite is the raw material from which alumina is produced. Alumina is processed into aluminium, one of the world’s most used metals. In 2023, Guinea produced 97mn tonnes of bauxite, making it the second largest producer worldwide by a slim margin with Australia top with 98mn t and China third with 93mn t (see figure 1). Each accounted for just shy of a quarter of global production. However, Guinea is distinctive as having the world’s largest bauxite reserves, estimated at 7.4bn t. The country also has substantial high grade iron ore reserves and commercially viable quantities of graphite, manganese and nickel.

Bauxite is not rare and it is not a high value commodity. Global reserves stood at 30bn t in 2023, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS), implying a reserves-to-production ratio of 75 years, but total resources are estimated at between 55-75bn t.

The USGS states that domestic bauxite resources are inadequate to meet long-term US demand, but there are essentially inexhaustible sub-economic alternative sources of alumina, such as clays. Both the US and EU include aluminium on their lists of critical minerals.

The International Aluminium Institute estimates aluminium demand will rise 40% by 2030 as consumption increases in the construction, packaging, transport and power sectors. The metal is considered a key element in the energy transition.

Bauxite mining in Guinea

Guinea’s open pit bauxite mining has expanded massively in the last decade, rising more than five-fold since 2014. Most of the government’s revenues come from the sector. Two companies dominate production; Société Minière de Boké (SMB) and Compagnie des Bauxites de Guinée.

SMB announced in February that it would invest between $0.5-1.0bn over the next five years to upgrade its river terminals and shipping capacity. It sells its production exclusively to its Chinese shareholder Shandong Weiqiao.

Compagnie des Bauxites de Guinée is 49% owned by the state and 51% by Halco mining, which, in turn, is owned by US aluminium producer, Alcoa (45%), Canada’s Rio Tinto Alcan (45%) and Dadco Investments (10%), a European investment holding company, which includes Dadco Aluminium.

Developing countries are pushing to retain more of the value chain from the production of raw materials. Measures include moratoriums on the export of unrefined materials such as rare earth elements. In 2023, Zimbabwe, Ghana and Namibia introduced bans on the export of unrefined lithium ore and other critical minerals.

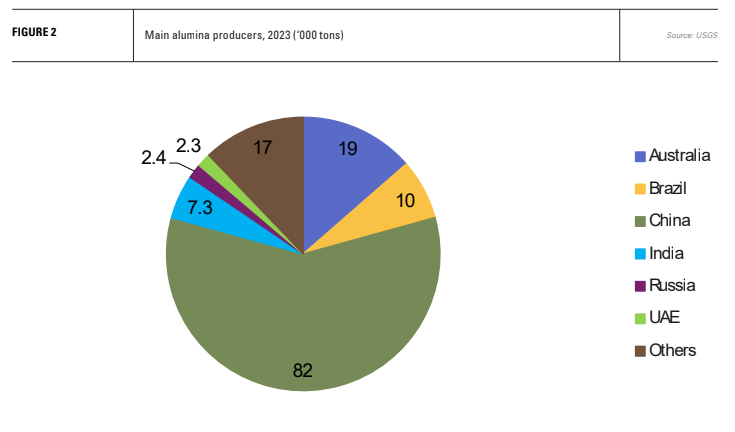

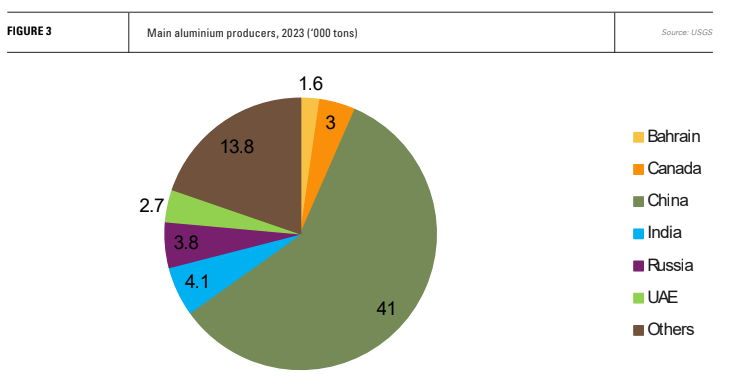

Guinea’s military junta is following a similar path, pushing bauxite producers to refine more of the material domestically. Despite its extensive bauxite mining, in 2023, Guinea produced just 330,000 t of alumina from its single alumina refinery, Friguia, owned by Russian aluminium producer Rusal (see figures 2 and 3 for current top producers of alumina and aluminium).

In June, a subsidiary of Emirates Global Aluminium and the Aluminium Corporation of China signed a non-binding agreement for the construction of a large alumina refinery in the country, which, if built, will produce 1.2mn t/yr from 2026. The joint venture project is in addition to five others which are at some stage of development. In total, the plans could see the country’s alumina production capacity increase to 11mn t/yr.

Bauxite mining requires diesel to power machinery and then transportation fuel to run export logistics chains. In contrast, alumina refining is more energy intensive and requires large amounts of power generated on site or close by.

Alumina, power and LNG

Guinea’s power system is small and its transmission and distribution system unreliable and under-developed. Although electricity access is better in urban areas, only about a third of the population have access overall.

Generation consists of 814 MW of hydroelectric capacity, a small amount of solar and around 250 MW of diesel or heavy fuel oil generators. A 105-MW Karpowership vessel supplied the capital Conakry with electricity from 2019 to 2023.

The country’s two largest hydro projects, Kaleta (240 MW) and Souapiti (450 MW) were both built by China International Water & Electric Corporation. About 390 MW of new hydro is under construction or close to the start of construction, while the 294 MW Koukoutamba dam is at the feasibility study stage.

Powering the planned 11mn t/yr of alumina refining capacity would absorb a majority of the country’s current generation capacity. With coal-fired power plants out of favour amongst international lenders, the proposed LNG import terminal and construction of gas-fired generation therefore look like the only option to meet the power needs of the planned alumina refineries. These would be the anchor customers on which LNG investment could proceed.

The lack of generation capacity explains why the government is not also pushing for aluminium production, which is even more energy intensive than the refining of bauxite into alumina.

Given its energy intensity, the price of electricity must be low for aluminium production to be competitive. Aluminium production is typically sited close to cheap sources of power rather than bauxite mines. LNG would struggle to be a cheap enough option for aluminium production because of the additional costs of liquefaction and transportation, when compared with hydro power, conventional gas supplies or domestic coal.

The inclusion of future domestic gas development by West Africa LNG Group in the second phase of its proposal probably reflects longer-term plans on the part of the government to capture the full aluminium value chain – aluminium production powered by domestic gas.

LNG for economic development?

There is no gas market in Guinea for LNG beyond as yet unbuilt alumina refining capacity, which creates a major chicken and egg problem – will the would-be refiners commit to major investments without the prospect of fuel to power the refineries? And can West Africa LNG proceed without certainty of demand? Building the alumina refineries is a major challenge in itself, given a lack of basic infrastructure, domestic skilled workforce and an uncertain political environment.

The Guinean junta, which may or may not be planning a return to civilian rule, sees development of more of the aluminium value chain, and potentially a domestic oil and gas sector, as a means of economic development or at least increased governmental revenue.

There is also more than a whiff of Sino/US competition. Guinea’s bauxite exports accounted for some 70% of Chinese bauxite imports in 2023. China is building hydro dams to power the country, the US, it seems, is offering LNG to power alumina refineries.

Conakry is well placed to leverage this competition to gain the higher value investment it desires, which will create jobs and benefit the economy as measured by investment inflows and GDP. The LNG sector may well gain a new, albeit small, market. However, how far the benefits of this industrial project trickle down to the Guinean population remains highly uncertain. The West African context does not provide great grounds for optimism for an economic model based primarily on raw material extraction.