Lack of reform, financial runs leaves Lebanon’s energy sector in limbo [Gas in Transition]

Lebanon in recent months has taken a couple steps that could get its long-in-limbo offshore hydrocarbon exploration and development programme on track. But the country’s political deadlock and crippled economy raise doubts whether any oil and gas that is found can be brought on stream.

The needed institutional reforms will not take place until a new president is put in office – the post has been vacant since last year – and a new government is formed. At present, Najib Mikati is once again acting as caretaker prime minister.

The dominance of the country’s politics by Iran-oriented Hezbollah, let alone the confessional political interests that traditionally controlled politics in Lebanon, has left the country shattered, with few foreign governments or international institutions willing to take it seriously.

Commentators frequently cite Lebanon’s perceived offshore hydrocarbon resources as a means by which the country could pull itself out of its political and economic crises. But Lebanon is nowhere near a position that would enable an oil or gas discovery to provide anything beyond more than mid-term relief. Among other things, Lebanon lacks financial credibility and infrastructure. Natural gas distribution project plans have been drawn up, but without reforms and financing, it could take years for the necessary pipelines and power facilities to materialise.

Lebanon’s mired politics and its ever-worsening economic problems – which will not be resolved without parliamentary action on reforms before it can receive assistance from international financial institutions – has led some Arab commentators to write Lebanon off as a “failed state and an Iranian base hostile to all the countries in the region.”

In a recent editorial published by the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI), Arab columnist Khairallah Khairallah said: “2022 can be seen as the hardest year Lebanon has ever known, after it transpired that no reform of any kind is possible.”

Khairallah said the Arabs “have become accustomed to living without a Lebanon that has anything to export except captagon and other drugs.”

Hopeful signs

Lebanon has no choice but to make this situation change. As dire and disappointing as Lebanon’s travails may be, it has not been dismissed entirely. An example of this came in late January when QatarEnergy formed a partnership with France’s TotalEnergies and Italy’s Eni to explore and possibly develop Lebanon’s offshore blocks 4 and 9 in the East Mediterranean, after Russia’s Novatek was forced to leave the project in the wake of Russia’s invasion in Ukraine.

The agreement will give QatarEnergy a 30% stake in the licences, with TotalEnergies remaining operator with a 35% interest and Italy’s Eni a further 35%. The original partnership drilled one well in 2020 at Block 4 that showed only indications of natural gas. Further exploration in Block 4 is needed. Plans to move to Block 9 for another well in what is identified as the Qana/Sidon site were halted in 2020 because of the coronavirus pandemic and an expanded dispute with Israel over the southern maritime border, the delineation of which had been contested by Beirut for several years previous.

Lebanon made a new offshore claim to the UN that moved the maritime border to the south by a considerable distance, expanding the total offshore area in dispute to include areas considered part of the Israeli offshore where Greece’s Energean is developing the Karish and Tanin fields for the Israeli gas market. Beirut’s claim jeopardised the project and risked renewed conflict between Israel and Lebanon.

With considerable diplomatic effort, the US state department arranged a framework agreement between the two perpetual enemies in October 2022 that TotalEnergies and Eni agreed to several weeks later. Hezbollah agreed to the deal, otherwise it would never have gone forward.

TotalEnergies said in a statement on November 15 that the partners would start exploring Qana/Sidon, which could extend both into Block 9 and into Israeli waters south of the maritime border. “We will respond to the request of both countries to assess the materiality of hydrocarbon resources and production in this area,” TotalEnergies CEO and Chairman Patrick Pouyanne said in the statement.

The group is now lining up a drilling rig, mobilising teams and purchasing equipment. Drilling is expected to begin in the third quarter of this year, according to Mona Sukkarieh, political risk consultant and co-founder of Beirut-based Middle East Strategic Perspective.

“An actual discovery of gas or oil might restore some financial credibility for Lebanon,” she tells NGW, adding that a find might lead to a “genuine effort to improve the plight of the people, although this could take a long time.”

Sukkarieh says the success rate for the planned well is 20%, and so expectations “should be held in check.”

The maritime agreement allows for the operator to transit through areas south of the border, if necessary, in order to carry out its activities without objections from the Israelis. Furthermore, Israel could not “unreasonably withhold” consent to drilling taking place south of the maritime border if that also proves necessary. Should a discovery be made, Qana/Sidon would be developed for the exclusive use of Lebanon, even if the reservoir extends into the Israeli exclusive economic zone (EEZ). But TotalEnergies and Israel would need to reach a financial arrangement. Shortly after the US-sponsored deal, TotalEnergies and partners signed an agreement with Israel on a compensation mechanism.

Licensing prospects

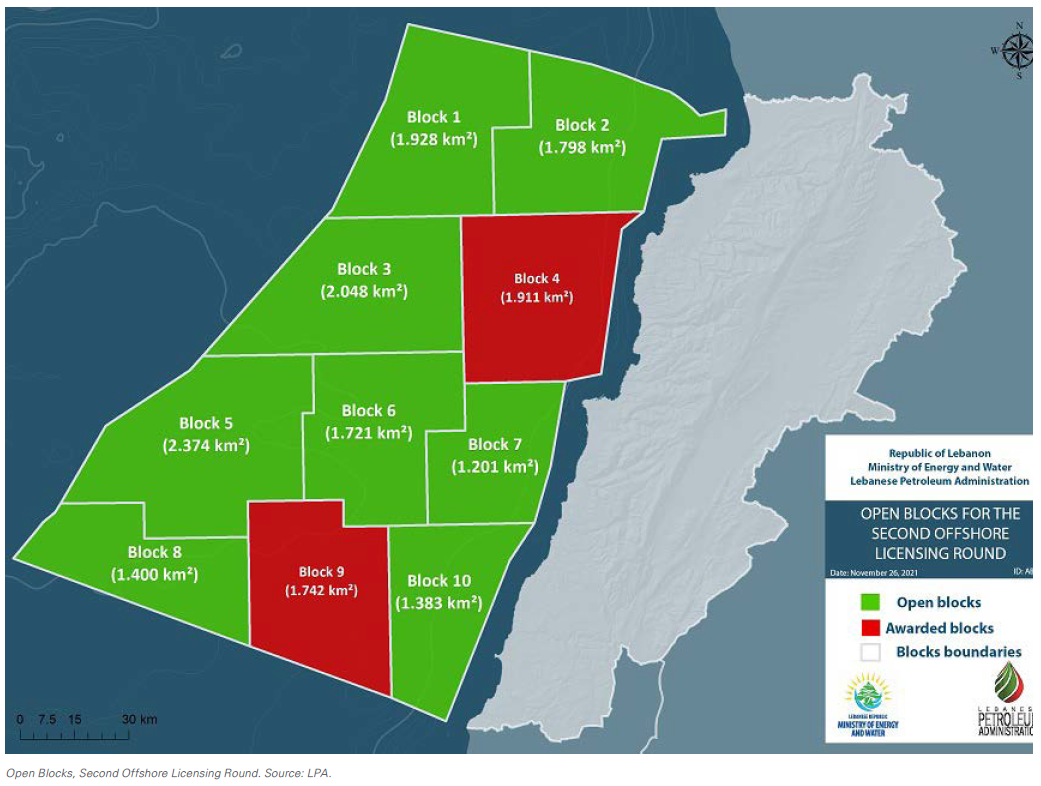

The maritime agreement also prompted the Lebanon Petroleum Authority (LPA) to extend its existing, but dormant, licensing round until June of this year. The LPA hopes that the maritime agreement will dispel concerns held by potential participants about bidding for Lebanon’s offshore blocks. Eight blocks are available for exploration – all of Lebanon’s blocks with the exception of Blocks 4 and 9, which were awarded to the TotalEnergies group in 2018.

Lebanon opened its first licensing round in 2013 and much of its offshore territories have been surveyed with 2D and 3D seismic, but domestic politics prevented the licensing round from concluding until 2017. With the maritime agreement with Israel now in place, the current round could attract a number of bidders, depending on how they read the geological data available.

Pipe plans

Another issue hitting Lebanon’s energy sector is a stalled plan to import Egyptian gas into Lebanon through the Arab Gas Pipeline (AGP), which transits Jordan and Syria. The plan, which has been in the works for nearly two years, remains hung-up on questions regarding US sanctions against Syria and reforms for Lebanon’s electricity sector. The plan calls for not only Egyptian gas being shipped to Lebanon, but also for up to 700 MW of Jordanian-generated electricity to be transmitted to Lebanon via Syria.

Egypt wants political and legal guarantees from the US that Egyptian companies will not suffer the consequences of Syrian-focused sanctions. The World Bank, which is prepared to release some $300mn to cover the cost of Lebanon’s energy imports, insists that reforms be implemented that require the restructuring of Lebanon’s national regulator and that losses caused by power grid leaks or theft be accounted for.

“From the start, it was obvious that there was a sequence of events to be undertaken to see the project move forward,” Sukkarieh says. “The first step was to reform the electricity sector in order to take the next step, which is to unlock World Bank financing before the following step: obtaining solid US guarantees that the entities involved would not be subject to Syrian-related sanctions.”

“Certain measures were indeed adopted by Lebanon to rehabilitate the electricity sector,” Sukkarieh adds, “but they were deemed insufficient by the World Bank.”

Considering the history alone, reaching the maritime agreement with Israel required considerable effort by the political powers in Beirut. But exceptional effort will be required from the domestic political powers and their cohorts if Lebanon is to get past its difficulties.