Jonathan Stern’s wake-up call for the European gas industry [Gas Transitions]

No one can accuse Professor Jonathan Stern of being anti-natural gas. As founder (in 2003) and long-time Director (until 2011) of the prestigious Natural Gas Research Programme of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES), and author of countless articles and books on gas, he has always been intimately involved in the international gas industry. Yet he has also stubbornly refused to become a mouthpiece for that same industry. The reputation of OIES is built on that independence.

Lately – he has a free role now at OIES as Distinguished Senior Research Fellow – Stern has been taking an increasingly critical view of the future of the European gas sector.

In 2017, he wrote two papers - The Future of Gas in Decarbonising European Energy Markets: the need for a new approach and Challenges to the Future of Gas: unburnable or unaffordable? – warning that the optimistic “gas-as-a-bridge-and-ideal-back-up for renewables” narrative of the European gas industry was being challenged by the decarbonisation objectives of the European Union.

He published a third paper February 5, Narratives for natural gas in decarbonising European energy markets, in which he warns that the European industry will not only have to start developing a new “narrative”; it will also have to start taking real action to make that narrative come true. Actions, he adds, that are not profitable today – and may not be profitable for a long time to come.

In Stern’s words: “… the [European] gas community needs to be clear that, although government funding and regulatory support will be needed to achieve decarbonisation targets, very substantial corporate investment in projects for which there is currently no business case, need to be part of its narrative.”

International conferences

How does he arrive at this conclusion? Stern notes first of all that the “traditional” gas advocacy narrative of the gas industry – based on the benefits of coal-to-gas switching and using gas as backup for renewables – will not suffice beyond 2030. The use of gas does “result in early emission reductions”, but “these will not be sufficient to meet 2050 COP21 commitments”.

This is not a new insight of course. Even an organisation like Eurogas, which represents the European gas industry, acknowledges the need, in view of the Paris Agreement, to switch to “decarbonised” or “renewable” gases. In response to the European Commission’s long-term vision to achieve a climate neutral Europe by 2050, “A Clean Planet for All”, published in November 2018, Eurogas noted that “the combined potentials of natural, renewable and decarbonised gas will help to achieve climate ambitions in time and will benefit quality of life and the environment also in terms of cleaner air, comfort and choice.”

Yet Stern feels that the gas industry is still largely taking a wait-and-see attitude. They are looking to policy-makers to put “technical, legal, fiscal and carbon price/tax frameworks in place”, he suggests, to help the industry develop decarbonised and renewable gas – rather than taking action themselves. “I do not hear the post-2030 issues being discussed at a high corporate level at international conferences,” Stern tells me.

Some industry executives may believe, deep in their hearts, that a future without natural gas is simply unthinkable. That assumption, Stern writes, would be “risky not only because it lets the gas (and other energy) industry ‘off the hook’ from taking any immediate action; but also because if this is proved to be incorrect (as this author believes it will be), governments may have decided that gas will not be part of a long-term energy future and there will be insufficient time to make decarbonisation preparations before unabated methane needs to be phased out.”

Outlier

As Stern points out in his most recent paper, the truth is that the post-2030 future for European gas is far from clear and not as bright as the industry likes to project.

Eurogas notes optimistically that “there is considerable potential to transition to renewable and decarbonised gases … Renewable gases like biogas and biomethane already play a significant role in some EU member states and contribute to the circular bio-economy. Innovation in other renewable and decarbonised gas production and use, such as hydrogen and synthetic methane via power-to-gas processes, is already in development.”

Stern takes a less optimistic view. With regard to “renewable gas”, he notes that the “maximum projected availability” of all “renewable gas” (that is, biomethane plus “green” hydrogen, i.e. based on electrolysis with renewable power) in 2050 “is equivalent to 25% of European gas demand at 2010 levels”. However, that 25%, which is the outcome of a 2018 study by consultancy Ecofys (“Gas for Climate”), is an outlier: “Most studies have much lower estimates.”

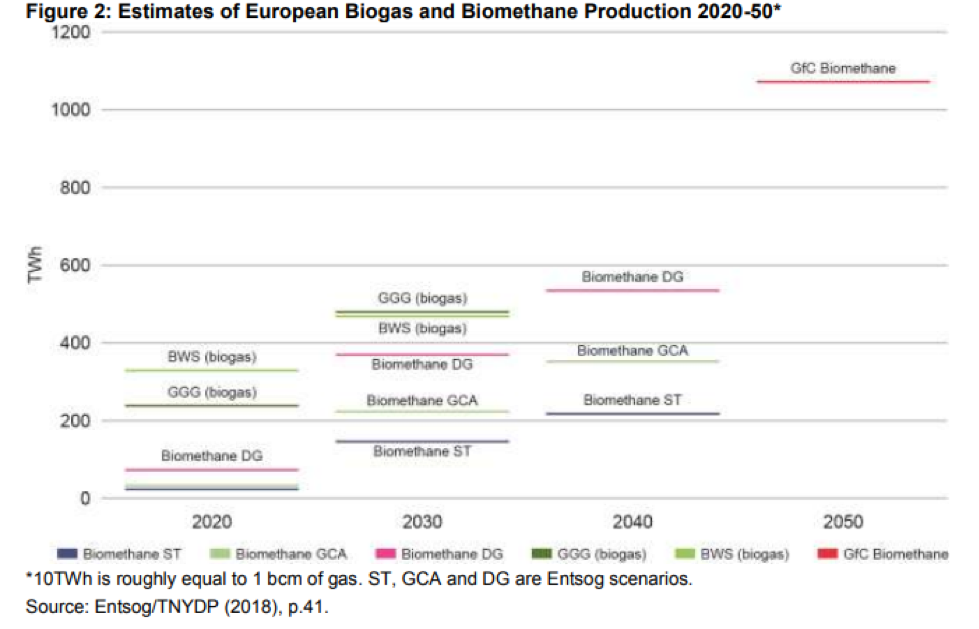

The figure below, taken from Stern’s paper, shows various estimates of domestic biogas and biomethane production for Europe in 2050 (note that current EU gas consumption is around 465bn m³/yr or roughly 4650 TWh/yr):

This figure makes it clear that, contrary to what Eurogas suggests, the “potential” of domestically produced biogas and biomethane is actually quite limited. Importing large amounts of biogas or biomethane hardly seems an option either.

This figure makes it clear that, contrary to what Eurogas suggests, the “potential” of domestically produced biogas and biomethane is actually quite limited. Importing large amounts of biogas or biomethane hardly seems an option either.

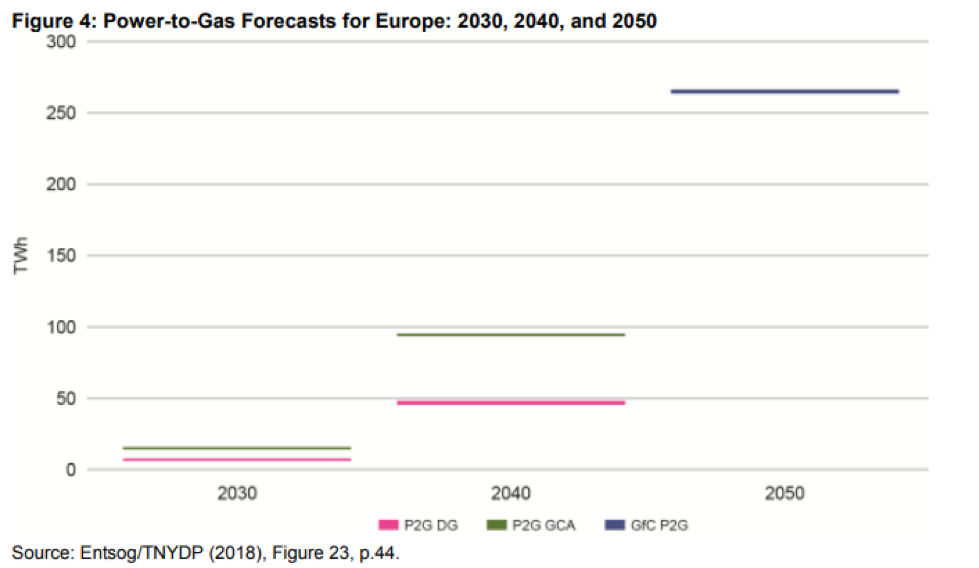

The potential of “green hydrogen” (power-to-gas based on renewable energy), on which the industry is also pinning some of its hopes, seems even more limited, as this figure shows:

This leaves the third option: “blue hydrogen”, i.e. hydrogen made from natural gas through the process of methane reforming (SMR or ATR), combined with carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Stern concludes that since the potential of “renewable” gas is limited, there will be “a need for very substantial volumes” of blue hydrogen, “if the gas industry is to maintain anything resembling current demand levels.”

And there’s the rub: blue hydrogen may sound good in theory but in practice very little is happening on the CCS front in Europe. There are some projects in the UK which have reached the feasibility study stage, such as the H21 project in the north of England, and one or two in the Netherlands, such as the Porthos project in Rotterdam and the Magnum power station, but these are all in their initial stages. No FIDs have been made on any of them.

Network companies

All of this makes the future of the European gas industry increasingly uncertain, according to Stern.

Interestingly, he argues that the transition will be more of a threat to network companies (transmission and distribution) than to gas producers and suppliers. I had always assumed that network operators would have less to fear, since they could switch from transporting natural gas to other gases, whereas gas producers would go out of business if there was no demand anymore for natural gas.

But Stern has a different take on this: “Pipeline gas exporters such as Russia and Norway can either decide to convert to hydrogen or phase out their pipeline exports – Russia has a large domestic market and (potentially) an alternative Asian pipeline market”, he tells me. “LNG exporters can either decarbonise the product at regasification, or ship hydrogen, or focus on other markets which will decarbonise significantly later than Europe.”

By contrast, says Stern, network operators are faced with “an existential threat”. Since “biomethane can only supply a fraction of the current throughput of networks, unless we have large scale hydrogen, many will go out of business.”

All this means that for the European gas industry, there is no time to waste. As Stern writes: “The necessity to demonstrate that the different decarbonised gas options are realistic and cost-effective against alternative low/zero carbon options is urgent, in order to provide sufficient time for a large-scale gas network transition over the following 25 years up to 2050. This means that the pilot projects currently in operation will need to be followed relatively quickly by commercial scale projects in order to be operational by 2025…”

He adds that “gas stakeholders – and especially gas networks – do not have another 10 years to continue to discuss and debate their future. Investments in the first commercial scale projects need to be rolled out by the mid-2020s to demonstrate successful large scale technical and commercial viability which could provide gas networks with life extension beyond the 2040s.”

Stern emphasises that his analysis only applies to Europe generally and to the major European gas markets in particular, “where governments are committed to rapid decarbonisation” – the UK, Netherlands, Germany, France, Belgium, Italy, and Spain. “For many other European countries (and especially outside Europe and the OECD in general) air quality, affordability and security concerns are much higher on the energy policy agenda than decarbonisation.”

How will the gas industry evolve in the low-carbon world of the future? Will natural gas be a bridge or a destination? Could it become the foundation of a global hydrogen economy, in combination with CCS? How big will “green” hydrogen and biogas become? What will be the role of LNG and bio-LNG in transport?

From his home country The Netherlands, a long-time gas exporting country that has recently embarked on an unprecedented transition away from gas, independent energy journalist, analyst and moderator Karel Beckman reports on the climate and technological challenges facing the gas industry.

As former editor-in-chief and founder of two international energy websites (Energy Post and European Energy Review) and former journalist at the premier Dutch financial newspaper Financieele Dagblad, Karel has earned a great reputation as being amongst the first to focus on energy transition trends and the connections between markets, policies and technologies. For Natural Gas World he will be reporting on the Dutch and wider International gas transition on a weekly basis.

Send your comments to karel.beckman@naturalgasworld.com