Japan’s pivot from gas to coal [NGW Magazine]

Prime minister Shinzo Abe’s September reshuffle coincides with a forecast that Japan is turning towards coal and away from natural gas.

Few countries face as intractable a set of issues as Japan in resolving the “energy trilemma” – the conflicting imperatives of making energy supply secure, affordable and environmentally sustainable.

The two people now most involved in resolving this trilemma will be: Isshu Sugawara, the new head of the ministry for the economy, trade and industry (Meti), whose responsibilities include energy; and Shinjiro Koizumi, a 38-year-old rising political star who has just been appointed to his first cabinet post as environment minister – and who is widely seen as a possible future prime minister. Both men face unenviable tasks.

Under the shadow of Fukushima

Eight years on from the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, all aspects of energy policy in Japan are still seen through the lens of the consequent nuclear accident at Fukushima. Before the accident a fleet of 54 reactors was supplying 30% of the nation’s electricity; by 2014 all the reactors had shut down. Despite impressive efforts to conserve energy and boost efficiency, the economic consequences were dire.

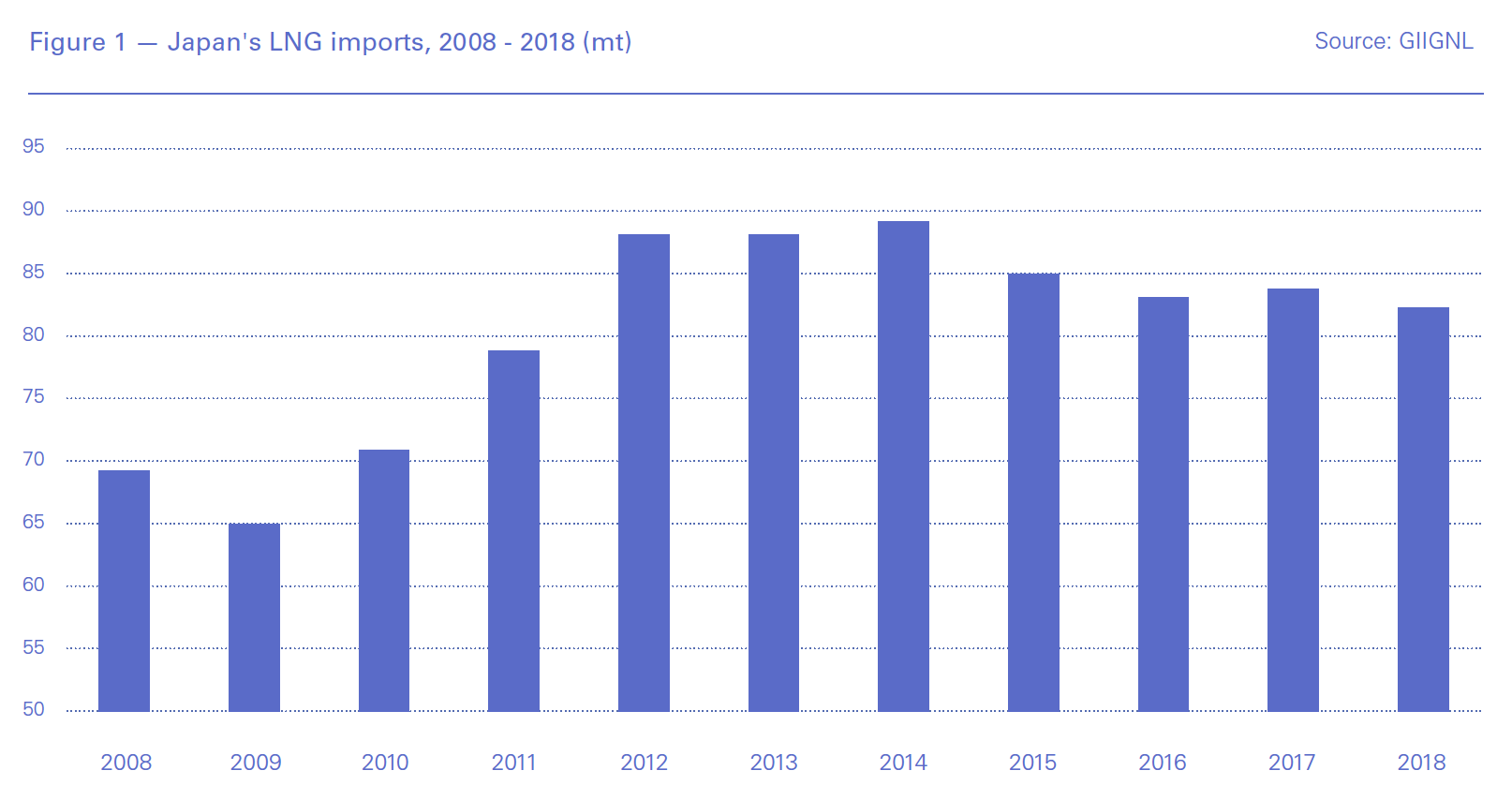

Japan was forced to ramp up imports of fossil fuels, especially LNG, just as oil prices surged above $100/barrel, where they remained until the oil price collapse of 2014. LNG imports in 2010 were 70.9mn metric tons (mt). By 2012 they had risen by a quarter to 88.1mn mt. They peaked in 2014 at 89.2mn mt but have since fallen back to 82.5mn mt.

With most LNG imports into Asia indexed to oil prices and spot prices at record levels, Japan had no option but to pay very high prices for LNG. Electricity costs soared, as did the trade deficit and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Energy self-sufficiency collapsed from an already low 20% in 2010 to just 6% by 2013.

Strategic Energy Plan

Current policy, as set out in a Strategic Energy Plan (SEP) agreed by cabinet in July 2018, calls for self-sufficiency in primary energy to reach 24% by 2030. A key objective is to minimise electricity costs. Moreover, the plan confirms energy mix targets set in 2015, when Japan was formulating its 2030 climate pledge in its nationally determined contribution under the Paris Agreement. Its goal is to reduce GHG emissions by 26% from 2013 to 2030.

These policy targets look very challenging indeed without a large future contribution from nuclear power. The SEP sets a target for nuclear reactors to be supplying 20-22% of the nation’s electricity by 2030.

However, re-starts of nuclear reactors have happened much more slowly than the government hoped. This is partly because the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA), which was set up after the accident to replace the previous discredited agency, has imposed safety requirements among the most stringent in the world. But it is also because of the strength of public opposition to nuclear power. Legal battles over whether reactors should be allowed to re-start have been intense, with frequent verdict reversals.

Only nine of the 39 operable reactors have re-started and four of these will have to shut down again next year if the utilities that operate them fail to complete required anti-terrorism works by the set deadlines. It does not help that Koizumi has in the past made a name for himself by opposing nuclear power.

Coal-power surge

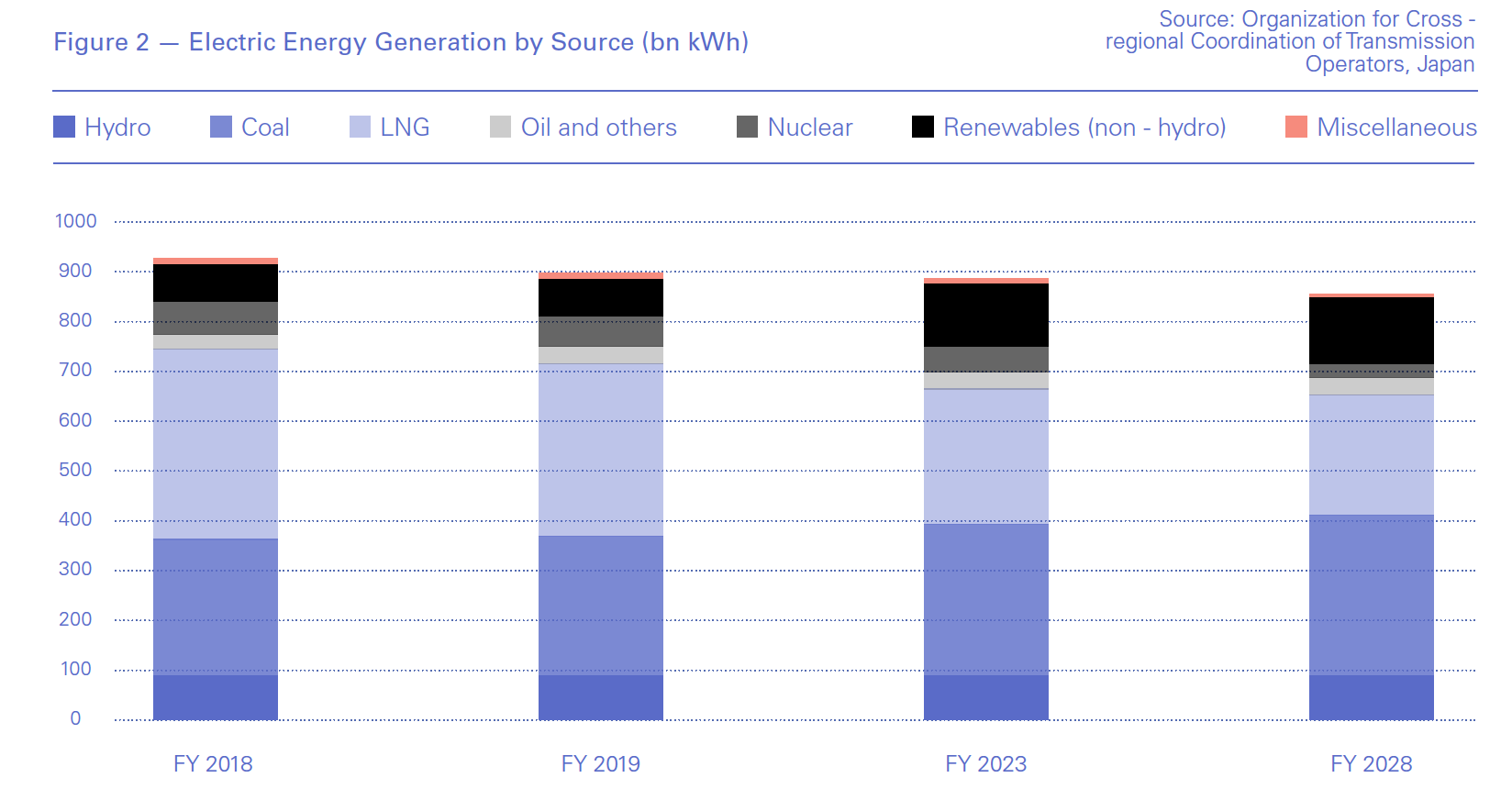

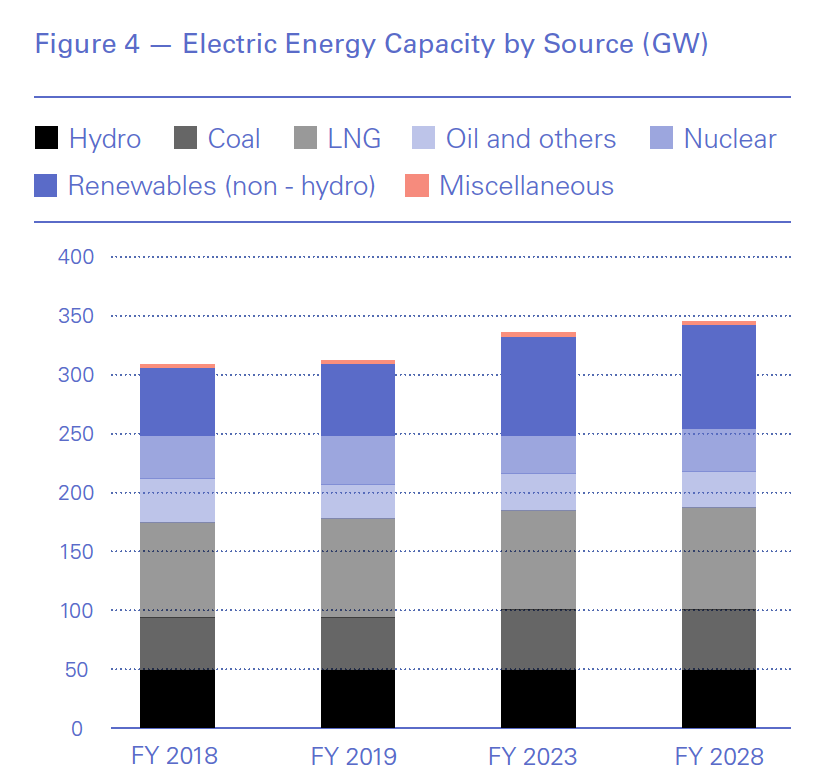

Meanwhile, forecasts from the electricity grid monitor OCCTO are at odds with the 2030 energy mix targets in the SEP. The charts below show OCCTO’s aggregation of electricity supply plans supplied by 1,299 electric power companies for fiscal year (FY) 2019.

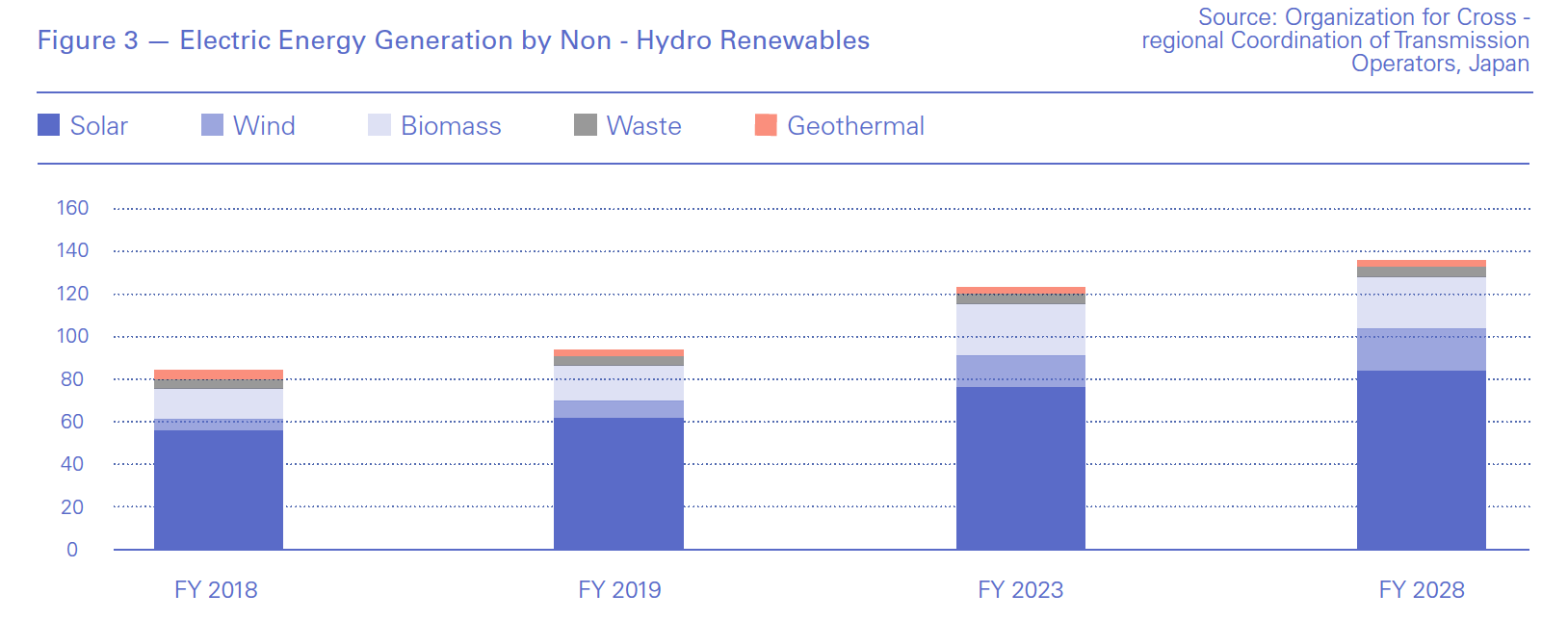

The forecast shows coal-fired electricity generation will become by far the largest source, with a share of 37% by 2028; meanwhile, LNG-fired generation, now the largest source, falls from 41% in 2018 to 29% by 2028. The SEP targets are for natural gas to remain the largest electricity generation fuel in 2030, with a share of 27%, ahead of coal, with a share of 26%.

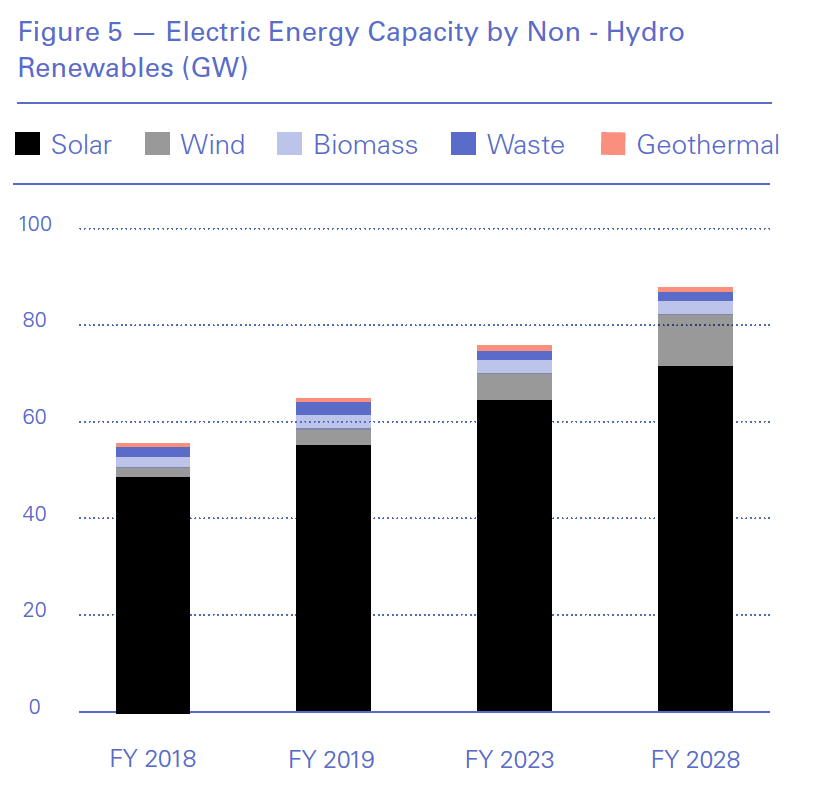

Non-hydro renewables grow strongly but contribute only 16% of total generation by 2028. Including hydroelectricity, the share rises to 26%, slightly higher than the 22-24% assumed for 2030 by the SEP.

The grid monitor takes a very cautious view of nuclear generation, assuming that any uncertain re-starts of reactors lead to zero generation; this is likely to underestimate the amount of electricity generated by nuclear reactors, but uncertainty around this remains very high.

The 20-22% share assumed by the SEP would require most of the existing operable reactors to be re-started and perhaps the construction of new ones if some of the currently operable reactors end up being decommissioned, as seems likely. And yet the SEP maintains a desire to “reduce dependency on nuclear power as much as possible” – highlighting arguably the greatest contradiction of Japanese energy policies and realities.

LNG’s “Asian premium”

So why the pivot from gas-fired power to coal-fired power, with all that that implies for GHG emissions, given that coal emits about twice the level of GHGs per unit of electricity generated than does gas?

The SEP not only describes coal as having the “lowest geopolitical risk and the lowest price per unit of heat energy among fossil fuels”, it also singles out LNG for its high price and cautions against “overly depending on it as a power source.

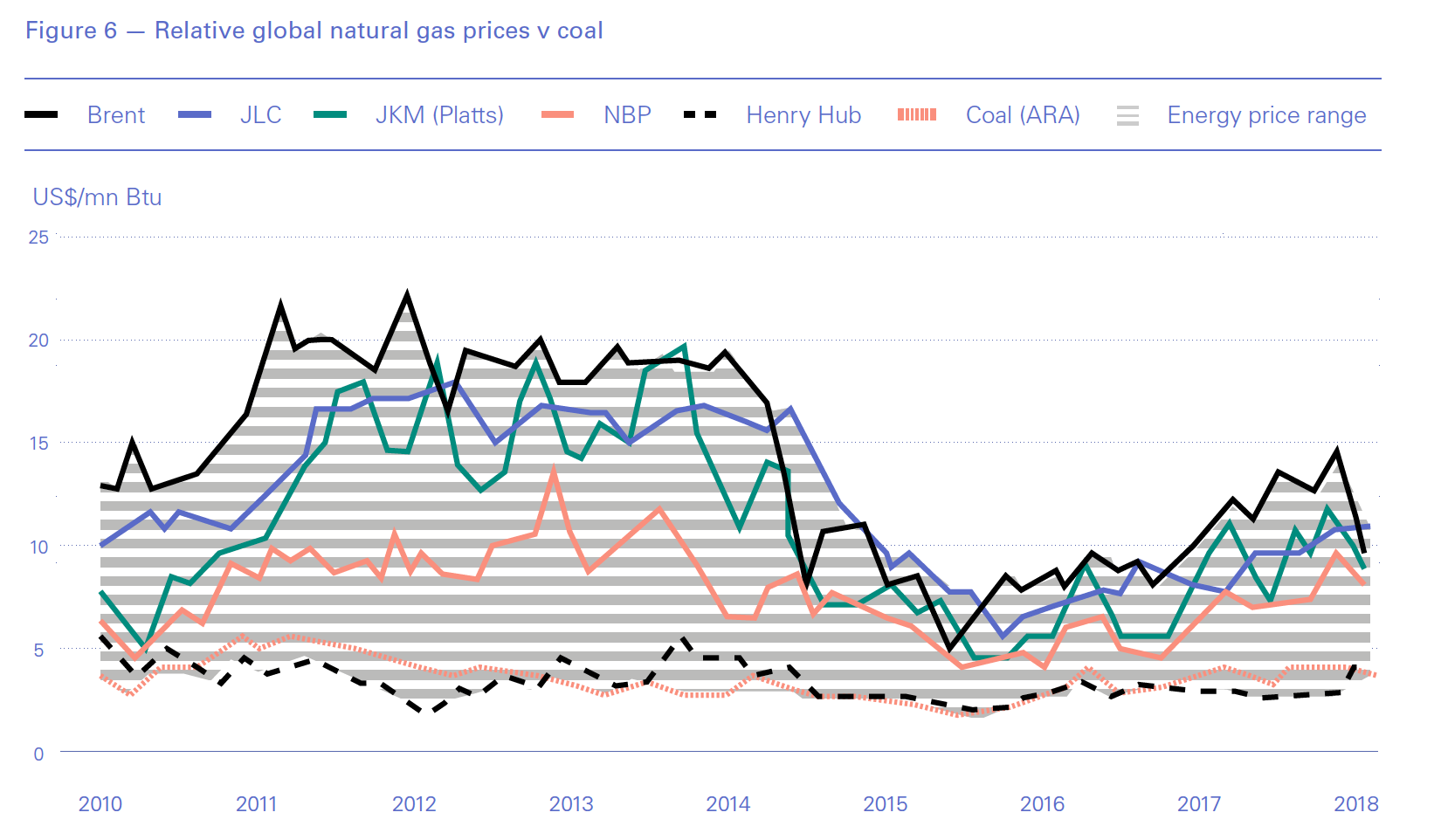

The chart below, taken from Shell’s 2019 LNG Outlook, helps to explain why substantial new coal-fired electricity generation capacity has been coming on stream in recent years and why OCCTO forecasts that coal-fired capacity will continue to grow, from 43.1 GW in 2018 to 51.9 GW in 2028.

It shows how global energy prices diverged during 2011-2014, when the Brent oil price rarely fell below $100/barrel. With most LNG imports into Asia indexed to oil, Japanese LNG buyers were paying much higher prices than gas consumers in Europe, where LNG is a price-taker; and they in turn were paying higher prices than gas consumers in North America, where the shale revolution kept gas market prices at very low levels.

Japanese power companies repeatedly warned that if this “Asian premium” persisted, they would look increasingly to coal – and they have.

Low load factors for gas

Low load factors for gas

There are inevitably implications for the owners of gas-fired power plants in terms of the load (or capacity) factors they can expect to operate at.

According to OCCTO, in 2018 Japan had 82.0 GW of gas-fired electricity generation capacity, almost double that of coal-fired plant. And while this capacity is expected to grow only marginally by 2028, to 84.9 GW, the steep decline forecast in gas-fired electricity generation, from 381bn kWh in 2018 to 250bn kWh in 2028, will see average load factor fall from 53% to just 34%. Coal by contrast goes from 73% in 2018 to 70% by 2028.

There has been talk that the SEP will be revised by 2021, putting pressure on Sugawara and Koizumi to address the glaring uncertainties and inconsistencies in current energy policy.

Climate emergency

On the current trajectory – even assuming many more nuclear plants are allowed to re-start – Japan will struggle to meet even its current NDC target for GHG emissions reductions by 2030.

The example of Germany is instructive: despite being a world leader in the deployment of non-hydro renewables such as wind and solar power, it will miss its 2020 emissions target because it did not address its high proportion of coal-fired electricity generation – much of which burns lignite, one of the most polluting of fuels. Belatedly, the government has just confirmed target dates for the gradual phase-out of coal in electricity generation.

Moreover, Japan, like the other signatories to the Paris Agreement, is under pressure to ramp up the ambition in its NDC, with revised versions due in 2020 and again in 2025. The past year has seen a palpable rise in international concern over climate change, with many now describing what is happening as a “climate emergency.”

The current estimated aggregated effect of all the NDCs submitted so far under the Paris Agreement falls far short of the central target of keeping global warming to “well below” 2 °C. Ambition ramp-up will be crucial.

Time for a plan B?

Time for a plan B?

The 2030 target for self-sufficiency in primary energy supply also needs the attention of the new energy and environment ministers.

Even before the Fukushima accident, Japan was exceptionally dependent on energy imports because it has few natural energy resources of its own. It even has to import uranium but the government regards nuclear power as a “quasi-domestic” energy source, partly because fuel is a very small proportion of its overall costs, and partly because once a reactor has been loaded with fuel it can operate for years. The only other significant domestic source of energy is from renewables, including hydroelectricity.

The 2030 self-sufficiency target of 24% is made up of a 13-14% contribution from renewables – which seems reasonable, given OCCPO’s forecasts – and a 10-11% contribution from nuclear power (derived from its assumed 20-22% share in electricity supply), which looks much less certain. The obvious question is: what will Japan do if nuclear power fails to get even close to the SEP target?

As for Japan’s LNG demand, the widespread assumption is that it will continue falling over the medium term as more nuclear reactors re-start, as renewable capacity surges, as more coal-fired generation capacity comes on stream, and as overall electricity demand declines. It won’t necessarily be so.