Iraq makes breakthrough in talks for oil, gas, water, solar project with TotalEnergies [Gas in Transition]

After almost two years of negotiations, a major Iraqi oil, gas, solar and water supply project looks set to make headway, after the government in Baghdad agreed this month to take a smaller stake in the TotalEnergies-led venture.

TotalEnergies signed a 25-year development and production contract for the enterprise, called the Gas Growth Integrated Project (GGIP), in 2021, but finalising the deal was held up by Iraqi political disagreement. TotalEnergies had been vying for a majority stake in the project, while the Iraqi government had been pushing for 40%. But this month Baghdad agreed to take only 30%, held via the state-owned Basrah Oil Company. TotalEnergies will take a 45% interest, while QatarEnergy will take 25%.

The project will see TotalEnergies invest some $10bn in recovering gas at three oilfields that is currently flared, as well as build a seawater treatment plant that can provide water to boost oil recovery at fields in the area. In addition, TotalEnergies has committed to constructing a 1-GW solar power plant to deliver electricity to the Basrah regional grid. Under the agreement with Iraqi authorities, Saudi Arabian renewables developer ACWA Power will be invited to join this project.

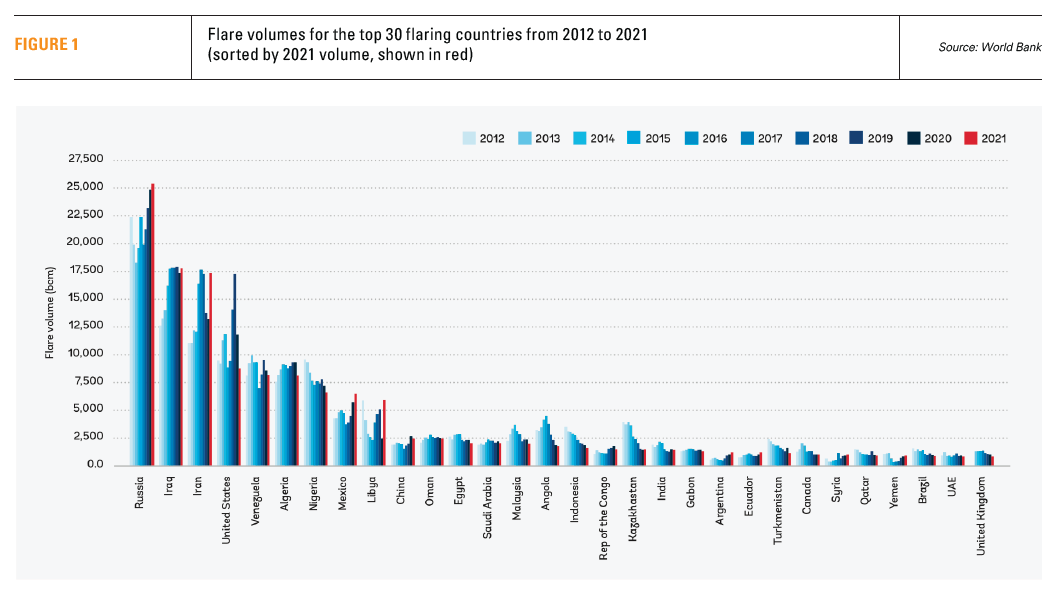

Iraq is the second-biggest gas flarer in the world after Russia, and despite government pledges to reduce volumes, they remain stubbornly high at around 17.5bn m3 annually (see figure 1), according to the World Bank. This would be enough to power 3mn homes, and has a lost sales value of $2bn at a price of $2.5/mn Btu, the bank estimates.

Baghdad also plans to invest in extra gas fields including Akkas and Mansouriya, as well as a string of associated gas projects.

Using more of its domestic gas resources also has important energy security considerations for Iraq, which periodically suffers blackouts because of insufficient power supply, and relies for about a third of its gas needs on expensive and not always reliable supplies from neighbouring Iran. Under the project’s first phase, enough currently flared gas will be saved to support 1.5 GW of power generation. That will be doubled in the second phase to 3 GW.

A tradition of flaring

Iraq’s high flaring activity comes from a long tradition of sidelining gas production and infrastructure in favour of developing more oil. But there largely still remains a lack of economic incentive. For oil companies exploiting the large-sized oilfields around Basra, it is cheaper to flare off associated gas than to capture, process and market it, because of low domestic gas prices.

The biggest offending projects, according to the World Bank, are the West Qurna 2 oilfield operated by Russia’s Lukoil, which flares nearly 1.2bn m3 of gas, followed by PetroChina’s Halfaya project (500mn m3), Basra Oil’s West Qurna 1 and Eni’s Zubair fields (450mn m3 each), Malaysian company Petronas’ Gharraf field (430mn m3) and Iraqi firm Missan Oil’s Buzurgan field (391mn m3).

The biggest offending projects, according to the World Bank, are the West Qurna 2 oilfield operated by Russia’s Lukoil, which flares nearly 1.2bn m3 of gas, followed by PetroChina’s Halfaya project (500mn m3), Basra Oil’s West Qurna 1 and Eni’s Zubair fields (450mn m3 each), Malaysian company Petronas’ Gharraf field (430mn m3) and Iraqi firm Missan Oil’s Buzurgan field (391mn m3).

Nevertheless, the government said in December last year it aimed to eliminate flaring completely within four years.

“GGIP is seen as the key to unlocking Iraq’s gas potential and to the reduction of flaring across the major oilfields in the south of the country,” Douglas McDonald, commodities analyst at Edinburgh-based IGM Energy, tells NGW. “While the development of the Akkas and Mansouriyah ‘free gas’ assets are important, the harnessing of associated gas that the GGIP covers – from the West Qurna-2, Majnoon, Ratawi, Tuba and Luhais oilfields – is perhaps a more vital turning point.”

“Since the development of these fields – and others – began, the technical services contracts signed by IOCs and NOCs did not cover gas production and as such, there was no way for the incumbents to monetise it, hence the decade or so of wasteful and damaging flaring,” he continues.

The deal with TotalEnergies and QatarEnergies is also a major coup for the Iraqi government following the withdrawal of several international oil companies in recent years, including BP, ExxonMobil and Shell. The key issue was Iraq’s political deadlock, which was finally cleared in October last year when lawmakers finally approved a new government, headed by prime minister Mohammeded Shia al-Sudani. According to Reuters, citing sources, al-Sudani’s government had been struggling to get out of a commitment from the previous administration to secure a 40% interest in the project..png)

Iraq’s oil ministry was also not keen on the renewables component of the project, sources told the Financial Times in October last year.

In February this year, Iraq’s oil ministry said that negotiations between the parties had been extended to sort out some “sticking points.”

“Some time has been given to continue the conversation to reach a solution that is agreeable to all parties, concerning some sticking points including the shareholding in the project,” ministry spokesman Assem Jihad said.

Tensions reached a head when TotalEnergies began ordering some staff to leave Iraq in February. The following month, CEO Patrick Pouyanne indicated that the company might lose its interest in the project because of mixed signals from Iraqi officials. Guarantees were needed that there would not be constant renegotiations, he said in an investor presentation.

“For the time being, we did not get it. If we don’t get it, to be honest, I cannot expose the company to a mix of risks because we know there is a security situation, we know the geopolitical situation,” Pouyanne told investors on March 21.

Water and oil

While gas capture is one of the main benefits for Iraq from the partnership with TotalEnergies and QatarEnergy, increasing the availability of water for the region will also be important. The Common Seawater Supply Project (CSSP) has been discussed for more than a decade. ExxonMobil was previously attached to the project, but pulled out in 2018 after failed talks. Originally the project was intended to supply only half as much water as the current deal with TotalEnergies.

Desalinated water from the plant will be critical for Baghdad to reach its target of expanding oil production to 7mn barrels/day by 2027, from the present level of just under 5mn b/d. That water will be pumped into the Rumaila, Halfaya, Zubair, West Qurna-1, West Qurna-2, Missan, Tuba and Majnoon oilfields.

“While there is certainly urgency to press ahead with each of the four elements – oil, gas, solar and seawater supply – pragmatism would suggest that the last of these should be prioritised given that desalinated seawater is key to Iraqi achieving its national oil production expansion target by 2027,” McDonald says.