IOCs and the carbon target [NGW Magazine]

At a meeting in Dubrovnik on 24 and 25 October, the European Strategy Forum considered European climate and energy policy.

The oil and gas sector is concerned about climate change and the need for transition to clean energy. But it also has a social responsibility to ensure that it happens smoothly, affordably and reliably without the lights going out.

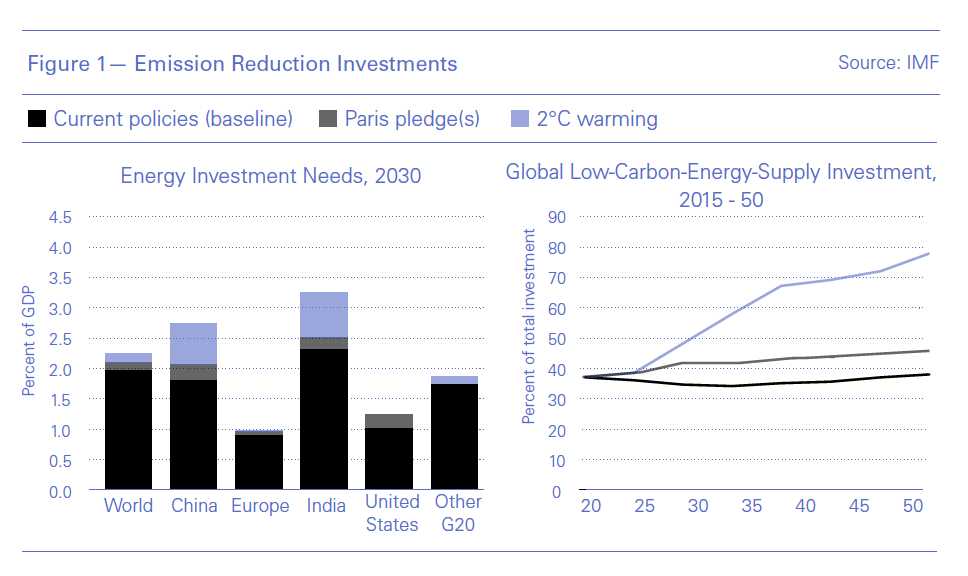

And it is not just energy in the affluent western European countries but also the rest of the world. Asia will continue to be home to most of the energy consumption and give rise to the most emissions. And according to IMF, that is where most energy investment on emissions reductions has to go (Figure 1), consistent with the official limit on temperature rises. But is the money there? India needs to invest 3.2% and China 2.7% of their GDP in low-carbon energy – which would be a challenge – while affluent Europe only needs to invest less than 1% of its GDP.

The oil companies are caught in a dual dilemma. Ensuring a smooth transition over the next 20 to 30 years to net-zero carbon means having sufficient, affordable energy for the world’s needs. At the same time, they are embarking on a pathway from a high to a low carbon future, in the hope of a permanent reduction of emission levels. The key issue is how to achieve the Paris Agreement goals without major disruption and unexpected consequences.

Renewables are making rapid progress and unit costs are coming down rapidly, but so far they provide less than 5% of global primary energy. It will be many years before they dominate.

In the meanwhile, and until that happens, natural gas, as the lowest carbon emitter of all fossil fuels, will remain very important.

IOC role

In order to get there the world will need step changes in technology, not just evolution. So how is this going to happen and by when?

Nobody can say confidently when the transition will be completed, so vilifying and demonising oil companies, to use BP CEO Bob Dudley’s words, is not the answer and may have unexpected consequences. There has to be a more sensible approach which will involve working with the international oil companies (IOCs).

The IOCs control only about 15% of the world’s oil and gas, so if the IOCs go, the national oil companies will step in and fill the gap. But an abrupt failure to provide affordable energy to societies used to it will cause even more anger than what has been seen today.

But if the IOCs go, the world will also lose a capability that can actually contribute to energy transition with investment, expertise and experience in driving major projects. The oil and gas sector is a global business with a global reach and knowledge and funding the sort of research that a smooth energy transition will depend on.

Shell is already investing $2bn to $3bn – close to 10% of its annual capital expenditure -- on electricity-related business. Other European majors are moving in the same direction. Equinor is building a floating windfarm off Norway to provide power to offshore platforms, instead of using gas turbines.

But as Shell’s CEO said recently it has no choice but to keep investing in gas and oil “because the world demands it.” All forecasts show – some more, some less – that the world will need gas and oil well into the future. It is not possible to drop them overnight – hence the use of the vague word, transition.

The IOCs are working to be part of this transition and what is needed is regulatory certainty. As Nick Butler writes in the Financial Times, the energy transition needs more than the private sector: it needs government support and public sector investment. “Embracing such an approach requires a recognition that renewables and wider low-carbon developments have a value beyond short-term financial returns and need distinct treatment,” he said.

European Green Deal

The European Green Deal can provide a sensible framework to drive the transition, within which the IOCs can work, provided it remains at high level. This is where the European Commission (EC) excels, being at one remove from national politics. It is good at setting up procedures and policies. However, imposing more and more ambitious targets and then trying to enforce them reduces credibility.

The Paris Agreement was a first step in the fight against climate change, with countries setting their own – one has to assume – achievable goals. But four years after it was signed, much of the world is not on track to achieve them. That includes the US and many of G7 and the G20 countries.

What is needed is a long-term framework, like the European Green Deal, to cover the period to 2050. It is based on today’s reality but it is capable of accommodating new technology and new realities.

It is difficult to say how well the EU has done in achieving its 2020 carbon emission reduction target. Some countries remain very heavily involved in coal-fired generation, despite the targets and even now the carbon price is too low, outside the UK, to make much difference (see below).

Second, the EU exported most of its high carbon emitting industries to developing countries without taking account of the associated emissions from manufacturing – possibly much higher than they would have been at home -- and from transporting the goods back.

Once all of these are factored back in, the picture is not so rosy. This is one reason why setting up very ambitious targets backfire. Targets should be worked out based on what is achievable and without an eye on the political timetable.

With the US president Donald Trump pulling the US out of the Paris Agreement, a European Green Deal to put climate change under a much-needed framework and give it direction is particularly timely.

Hard realities

Most surveys of public opinion, both in Europe and in Asia, show that people are aware of climate issues and want change, but are not prepared to undergo major changes to lifestyles and forego opportunities to improve their living standards. Small, easy, changes are not enough.

In fact Europe is facing an unexpected challenge. A third of all new cars sold in Europe are SUVs, consuming on average 25% more energy than medium-sized cars, leading to fast rising carbon emissions. SUV sales have also grown strongly in China.

Energy market projections are uncertain because the events that shape future developments in technology, demographic changes, economic trends, and resource availability that drive energy use are fluid.

And on top of this the world order, trade and even energy flows are being forced to readjust in response to global trade wars and sanctions and the resultant economic downturn. National energy security has risen to the top of the agenda in Asia – favouring domestic energy sources at the expense of imports, unless these come from what are deemed to be friendly countries. Renewables benefit from this, but so too do coal, indigenous oil and gas and nuclear.

This is convincingly reflected by the wide range of projections and forecasts of future global primary energy consumption in recently published comparisons. Out of the 18 reputable scenarios, only two expect the level of global primary energy consumption to be lower by 2040 in comparison to 2017. Leaving BP’s 2019 ‘more energy’ outlier scenario out, the rest expect this to grow between 10% and 40%, with an average of about 25% -- close to IEA’s ‘new policies’ and BP’s ‘evolving transition’ scenarios.

Almost all of this increase is in Asia, driven by population growth in India and China and also by better living standards.

There are also uncertainties in terms of the impact of technological advancements on the progress of renewable energy. Forecasts range from a 17% to 45% share of global energy to be provided by renewables by 2040. The average is 25%, close to Shell’s 2019 ‘ocean’ scenario. Even the highest forecast, 45%, is not enough to deliver a sustainable energy system, and so the world will still need oil, gas and coal by 2040.

The scenarios that project a reduction in future primary energy or a renewable energy share greater than 30% require step-changes in energy efficiency and technology and the way the world produces and consumes energy.

EU member states’ energy plans to 2030 were enthusiastic in recognising climate change as a serious issue but lacked ambition in the climate targets they set, and that was in the context of only a 40% cut in emissions by 2030 in comparison to 1990. It will be interesting to see what will happen if this is increased to 50% or even 55%, as promised by EC’s new president, Ursula von der Leyen.

Similar uncertainties are exhibited by comparisons of oil forecasts. Of these, half show oil demand still not at its peak by 2040. And only half show coal demand peaking before 2030.

So the variability is huge. It demonstrates that the world cannot take it for granted that fossil fuels will just be wished away. Public expectations are one thing, but the hard realities of what is achievable and when are another. That’s why IOCs are not about to abandon oil and gas.

Sensible policies

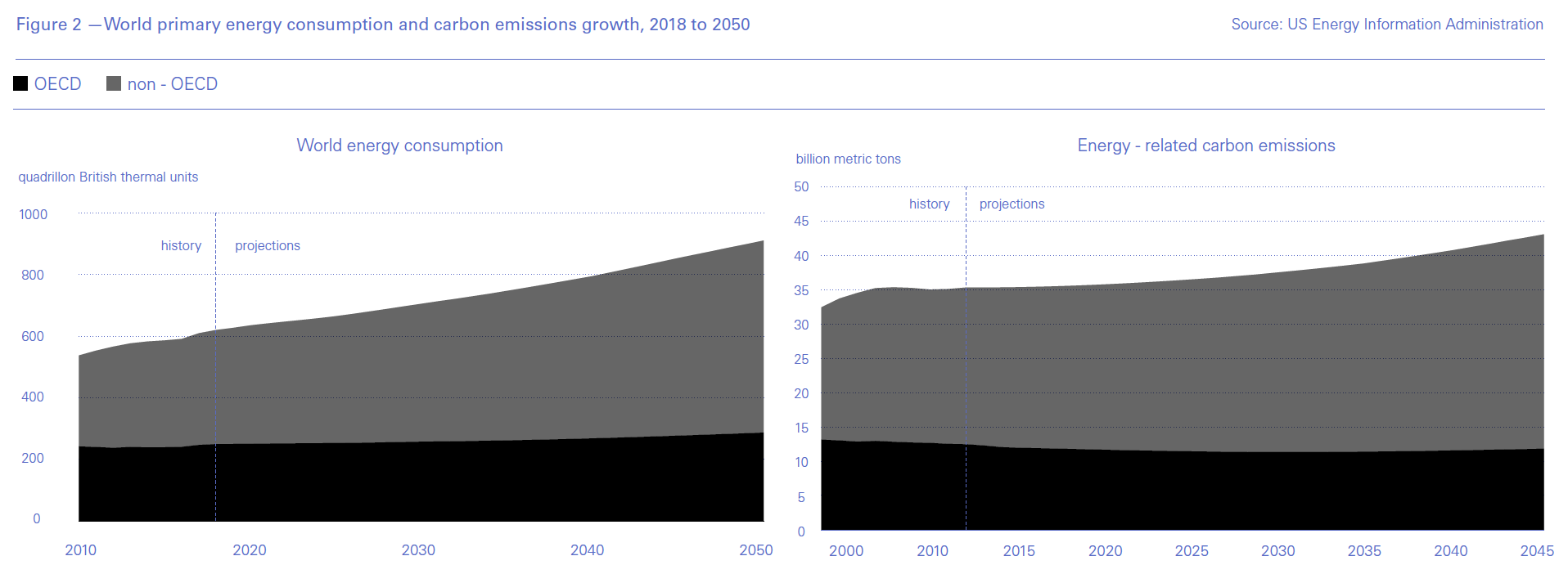

Even though environmental concerns and climate activism are growing fast in OECD countries, that is not necessarily the case in non-OECD countries where energy affordability and improving living standards take priority. By 2050 almost 70% of world energy will be consumed in non-OECD countries, which will also be producing more than 70% of the world’s energy-related carbon emissions (Figure 2).

It is due to these energy market projection uncertainties that the energy sector sees it as its obligation to ensure sufficient energy supplies are available while the world decides how to tackle energy transition and governments introduce appropriate policies to achieve that.

Aiming for decarbonisation by 2050 in the context of a unifying framework for Europe, such as the Green Deal may be the way forward.

Carbon pricing

The IOCs have been calling for economically meaningful carbon pricing. Following a climate change summit with the Pope in June, the major companies, including ExxonMobil, BP, Shell, Total, Chevron and Eni, said in a joint statement that governments should set such pricing regimes at a level that encourages business and investment, while “minimising the costs to vulnerable communities and supporting economic growth.”

This was also identified by the UN climate action summit in New York in September as one of the nine inter-dependent action tracks to accelerate action to achieve the Paris Agreement.

Given the success of schemes in Europe and the UK, there is now wider recognition that a carbon tax, or an emissions trading system with a price floor, could be the most effective way to influence emissions. But climate change will not be solved by any one country or region alone. To succeed, policy must be effective, legitimate and global.

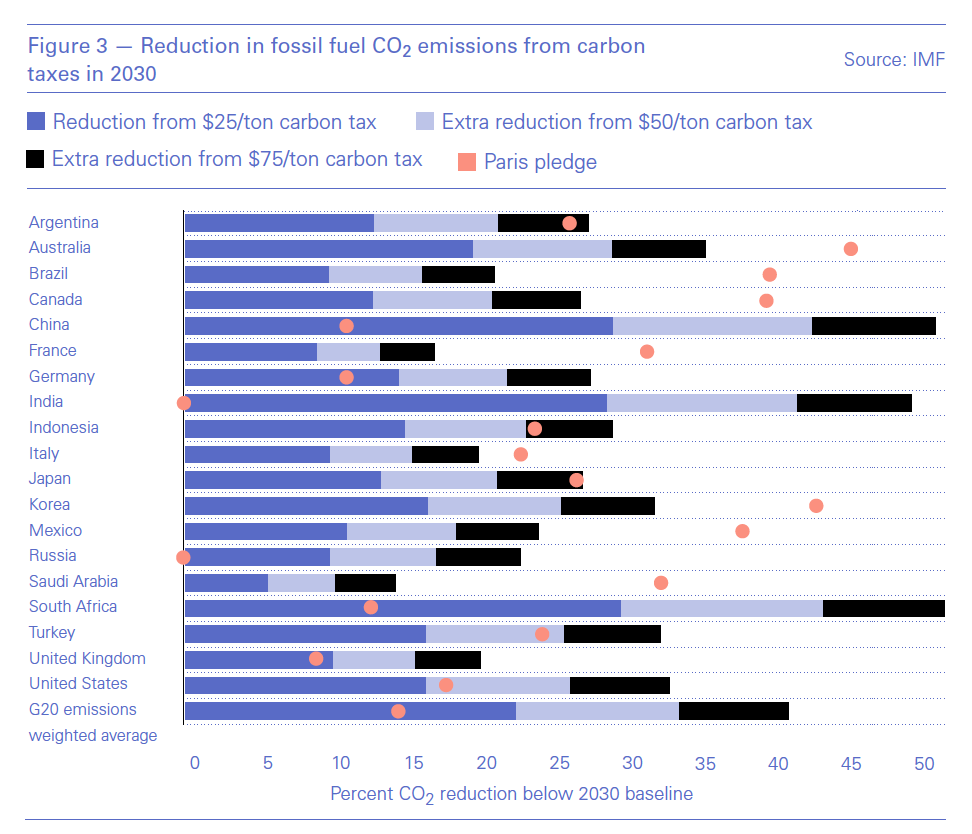

The IMF also argues in a recent report that “of the various mitigation strategies to reduce fossil fuel CO2 emissions, carbon taxes -- levied on the supply of fossil fuels… in proportion to their carbon content -- are the most powerful and efficient, because they allow firms and households to find the lowest-cost ways of reducing energy use and shifting toward cleaner alternatives.” It also makes recommendations on carbon prices countries must impose to implement their mitigation strategies (Figure 3) – and their impact on CO2 reduction -- and ways to minimise the costs to the poorest households and vulnerable communities. The latter is essential to give any such policies legitimacy.

The IMF report concludes that $75/metric ton of carbon might be the price in 2030 consistent with keeping the temperature increase below the ceiling. But such policy – as any climate action policies -- must be global with all major economies involved, to avoid carbon leakage as happened with some of Europe’s heavy industry.