Impact of Gaza war on East Med gas [Gas in Transition]

The Israel-Hamas war overshadows most other issues around the East Med. It is a crisis but, in terms of energy, what happens is dependent on the extent and duration of the fighting, whether Hezbollah gets further involved, what Iran may or may not do, associated geopolitical tensions and the possible occurrence of terrorist attacks. With no solution in sight, there is always a risk that the conflict could develop into a regional confrontation with potentially global consequences.

So far both Hezbollah and Iran have refrained from any direct involvement. But if the civilian death toll in Gaza carries on rising, the risk of wider conflagration increases. Right now, it is characterised by extreme uncertainty.

In global energy terms the concern is whether it will lead to oil and gas supply disruptions. Oil prices were already high before the war, because of Saudi Arabia’s and Russia’s decision to extend oil production cuts, and went higher immediately afterwards. But they have since declined below $80/b, implying that the oil markets do not see any immediate escalation dangers. The industry’s current base-case appears to be that the conflict will likely be largely contained to Israel and Gaza.

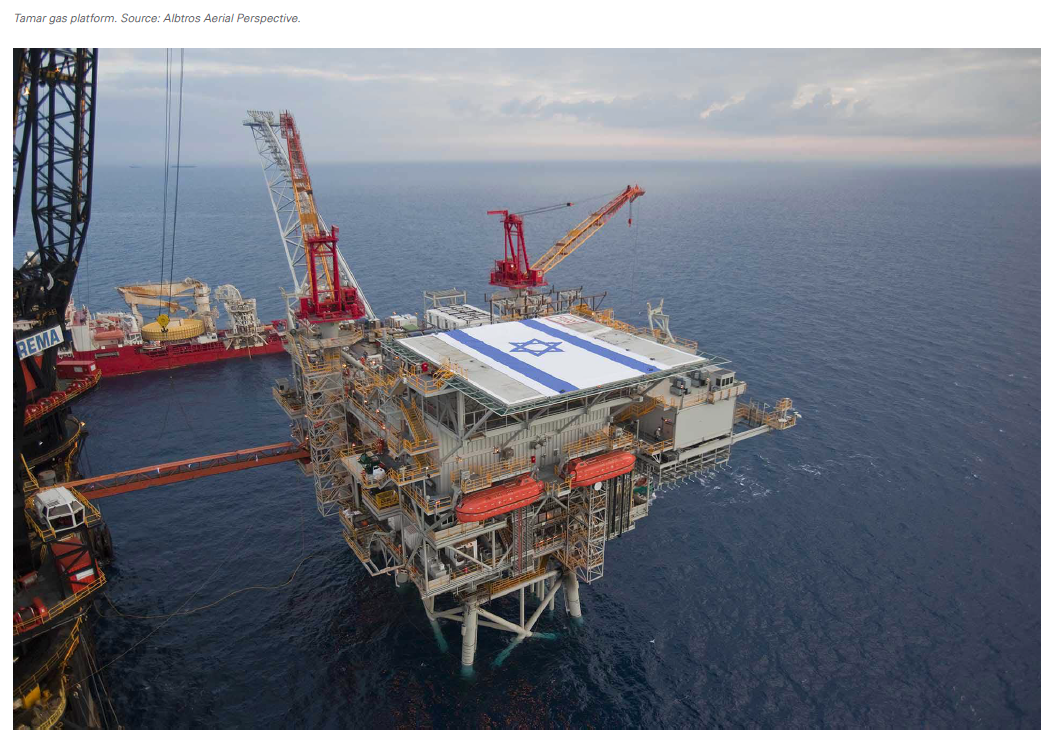

The war led to the Israeli government shutting-down operations at the Tamar gas platform, affecting gas supplies to Egypt. A number of attempts have already been made to attack the platform and even though production has restarted, with the war still raging, security risks remain.

This is not the first time it happened. Israel instructed Chevron to shut down operations at the Tamar gas platform during the week-long war between Israel and Gaza in May 2021.

The October shut-down reduced Egypt's gas imports from Israel, making it difficult for Egypt to meet domestic demand and export LNG. Standard & Poor expects this to affect Egypt’s already beleaguered economy further.

At one stage the impact on Egypt’s ability to maintain LNG exports also affected gas prices in Europe. But with Europe’s gas storages full, these have since declined.

For the East Med, these developments cast a shadow over the future development of its abundant gas resources. A long-running conflict could delay projects and final investment decisions and cause doubts and concerns in the minds of international investors that the geopolitical risk is too high.

Israeli gas supplies to Egypt

For about five weeks after the start of the Gaza conflict, Israeli gas supplies to Egypt were suspended, exacerbating the country’s already dire energy problems. This led to immediate power cuts and temporary reduction of gas supplies to energy-intensive industries, including fertilisers, showing how dependent Egypt has become on Israeli gas imports. When gas supplies tightened, earlier in November, Egypt was even forced to import an LNG cargo.

Lack of any new major gas discoveries since Zohr in 2015, and faltering production, coupled with ever-increasing energy demand due to its fast-growing population, has left Egypt exposed to energy shortages. Gas production already reached a three-year low in 2023 and it is still declining. Combined with its continuous economic problems, energy security and the economic crisis will be major issues at the country’s forthcoming presidential elections, scheduled to be held in December.

Lack of any new major gas discoveries since Zohr in 2015, and faltering production, coupled with ever-increasing energy demand due to its fast-growing population, has left Egypt exposed to energy shortages. Gas production already reached a three-year low in 2023 and it is still declining. Combined with its continuous economic problems, energy security and the economic crisis will be major issues at the country’s forthcoming presidential elections, scheduled to be held in December.

But, at least for now, Israeli gas supplies have been more or less restored to normal, pre-war, levels, close to 23mn m3/d, and the EMG pipeline is back in operation.

This should enable Egypt to resume some LNG exports, including to the EU. In June 2022, the European Commission, Israel and Egypt agreed to a supply of LNG to the EU up to 2030 to help the EU replace Russian gas. According to Eni, Egypt should be able to resume LNG exports in December or January.

But even then, Bloomberg estimates that Egyptian LNG exports could be 40% less than pre-war forecasts. It should be remembered that Egypt halted LNG exports during the summer as a result of having to divert its dwindling gas supplies to the domestic market due to the high power demand during the summer months.

In 2022 Egypt exported about 10bn m3 LNG to world markets, accounting for less than 2% of the global LNG trade. About 7bn m3 went to Europe, contributing about 5% to EU’s LNG imports in 2022. Even though this is a small proportion of the EU’s LNG imports, any disruption adds to its overall supply concerns.

However, with gas storages in Europe at full capacity, this will not have any immediate impact.

Egypt’s LNG revenues in 2022 were over $8bn, helping shore-up its economy and foreign currency reserves. These are expected to be substantially lower in 2023.

Israel’s gas fields

Gas production from Israel’s offshore fields started in 2013, with gas exports starting in 2020. By 2022 production reached about 22bn m3/yr, with just over 40% exported by pipeline to Jordan and Egypt.

Gas production has become important to Israel’s energy sovereignty, but its export has also strengthened Israel’s regional influence. As a result, its offshore installations have become a target in a dangerous neighbourhood.

It is the proximity of the Tamar gas platform to the Gaza Strip, about 20 km away, that makes it so vulnerable to attacks by Hamas.

Israel’s other operating gas fields, Leviathan and Karish, are located further north and, as a result, have been able to continue pumping gas. In fact, gas production ramped-up to cover the short-fall from the Tamar shut-down. Combined with the halt in gas exports, meant that, unlike its neighbours, Israel did not experience any energy shortages.

Nevertheless, all three gas-fields, and especially Karish, are close to Lebanon, making them vulnerable to any flare-up of hostilities with Hezbollah. As expected, they are all under heavy security protection.

As a demonstration of the country’s confidence in the future of its gas resources, and its growth ambitions, Israel’s Energy Ministry announced at the end of October that it had awarded 12 exploration licences to six companies to explore for gas in its EEZ. These included BP with Azerbaijan’s state-owned oil company SOCAR and Israel’s NewMed, and Eni with Dana Petroleum and Israel’s Ratio Energies.

In addition, according to Bloomberg, BP confirmed last month that it remains committed to the deal to buy a 50% stake in the Israeli oil and gas company NewMed, in partnership with Abu Dhabi’s ADNOC.

Importance of East Med gas

First, let's put East Med gas in context. Current East Med gas reserves constitute only about 2% of global gas reserves. Even for Chevron, the biggest gas player in Israel, the share of East Med gas in its global portfolio is only about 6%.

Nevertheless, all majors are operating in the region and see the East Med as important to their global hydrocarbon business.

Colin Parfitt, Chevron’s vice-president for midstream, confirmed in November that the company will carry on with its natural gas expansion plans in Israel, despite the Gaza war. “Ours is a long-term business,” he said. “You have to be able to see through some of this…There is gas there, there is gas in the East Med, you look at the world demand for gas, you look at European demand for gas – it still feels an attractive place for gas to supply.” He reiterated what Mike Wirth, CEO Chevron, said in October, that the Israel-Hamas war would not alter Chevron’s plans for the East Med. Wirth added that the company is taking a view “measured in years and decades” as it develops projects.

The company plans increasing gas exports to Egypt from about 8bn m3/yr in 2022 to about 20bn m3/yr by 2027. This has already been sanctioned by the Israeli government. Following the October pause, drilling has restarted at Tamar to expand production in support of these plans.

The company plans increasing gas exports to Egypt from about 8bn m3/yr in 2022 to about 20bn m3/yr by 2027. This has already been sanctioned by the Israeli government. Following the October pause, drilling has restarted at Tamar to expand production in support of these plans.

In addition, as part of Leviathan’s Phase 2 development, Chevron is considering installing a floating liquefaction facility (FLNG) at Leviathan to produce 4.6mn mt/yr for export to global markets, particularly to Asia, as well as expand production for export to the domestic market and to Egypt. The question, though, is when will Chevron take these plans forward? Will prolonged conflict in Gaza cause long delays? That would be detrimental to Egypt that is becoming desperate for a substantial boost of gas supplies from Israel. With its own gas production faltering, it needs Israeli gas to fuel its gas-fired power plants that provide about 75% of the country’s power supply and to maintain lucrative LNG exports.

Egyptian gas production may see an upturn in about three years. Eni hopes to restore higher production at Zohr, but also to start production from the 280bn m3 Orion-1 gas field in the Eastern Mediterranean part of Egypt’s EEZ. Chevron/Eni also hope to develop the 100bn-m3 Nargis gas field, north of Sinai, over the same period.

Cyprus could potentially help by sanctioning the development of the Aphrodite gas field and export the gas to Egypt. Eni is planning something similar with its gas fields in Cyprus’ Block 6, should appraisal of the Cronos prospect, currently in progress, be successful. But Cyprus is still weighing its options.

Supply of Israeli gas to Egypt also has a political dimension. Not only it helps Egypt’s power sector reduce power cuts that are often the cause of social unrest, but it has also contributed to strengthening diplomatic relations between the two countries. It is worth remembering that crippling power cuts contributed to the eventual downfall of Egypt’s previous President, Morsi, in 2013. For Israel the survival of President Sisi is considered to be a “vital security interest.”

East Med energy security concerns

The Israel-Hamas war has brought the question of East Med energy security and the geopolitics of energy back to the fore. Given the earlier Gaza crisis in 2021, the on and off clashes with Hezbollah and the hostility of Iran to Israel in the background, as well as the ongoing maritime disputes between Turkey, Greece and Cyprus, energy security concerns resurface frequently in a volatile region.

Iran’s foreign minister on October 18 called Islamic countries to boycott Israel, including stopping oil shipments, temporarily causing a jump in oil prices. This was not supported, but it brought back memories of the 1973 oil embargo imposed by Arab states for its support of Israel.

The longer the war lasts the higher the risks that it can spill into energy flows and markets, pushing prices upwards in a jittery world. Recently, Baker Hughes CEO, Lorenzo Simonelli, said that wars in Ukraine and the Middle East threaten instability similar to the 1973 oil embargo. He warned that “geopolitical risks are at their highest level in half a century, raising concerns about energy supplies.”

Escalation of the conflict into Lebanon, or into the West Bank, would certainly add to these concerns and make the situation that much more serious. However, based on the speech by Hezbollah’s leader, Nasrallah, on 3 November, this appears to be quite unlikely, despite the escalation in tension.

In addition, so far, Iran has been manoeuvring carefully, concentrating its efforts on the political and diplomatic front, avoiding direct confrontation with Israel and the US.

In the meanwhile, Turkey has weighed into the conflict, strongly supporting Hamas and stepping up criticism of Israel. However, its interventions so far are confined to harsh rhetoric, and tend to indicate that President Erdogan is trying to create a role for himself in the peace process that will follow the end of the conflict.

But Turkey’s stance has caused a halt in any discussions on joint hydrocarbon developments and on potential export of Israeli gas through Turkey. These are likely to remain on ice for a long time.

These developments create uncertainty and have the potential to derail confidence in the region and delay new gas developments, but the increased geopolitical risk can also increase their cost.

Diversifying energy sources by bolstering adoption of renewables -an abundant energy resource around the East Med- and interconnection, and by increasing energy efficiency, the countries of the region can massively improve their energy security and reduce emissions in the process. This could also reduce tension associated with hydrocarbon extraction and even improve cooperation. Unfortunately, this still remains work in progress.

But, at least for now, the Gaza conflict has remained a contained, regional, issue and as long as it remains so it should not have a wider impact.