IEA sees demand for all fossil fuels peaking by 2030 [Gas in Transition]

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) new World Energy Outlook 2023 (WEO), released in October, states that “major shifts underway today are set to result in a considerably different global energy system by the end of this decade.” It puts this down to “the phenomenal rise of clean energy technologies such as solar, wind, electric cars and heat pumps” that is reshaping how everything will be powered.

The key conclusions IEA draws in the outlook are:

The energy world remains fragile but has effective ways to improve energy security and tackle emissions – the emergence of a new clean energy economy, led by solar PV and electric vehicles (EVs), provides hope for the way forward.

The world is on track to see all fossil fuels peak before 2030 – the momentum behind clean energy transitions is now sufficient for global demand for coal, oil and natural gas to all reach a high point before 2030, with the share of fossil fuels in global primary energy dropping from about 80% now to 73% by 2030.

- China has changed the energy world, but now China is changing – momentum behind China’s economic growth is ebbing and there is greater downside potential for fossil fuel demand if it slows further.

- New dynamics for investment are taking shape - the key to an orderly transition is to scale up investment in all aspects of a clean energy system.

- Meeting development needs in a sustainable way is key to moving faster - clean electrification, improvements in efficiency and a switch to lower- and zero-carbon fuels are key levers available to emerging and developing economies to reach their national energy and climate targets.

- Ample global manufacturing capacity offers considerable upside for solar PV – renewables are set to contribute 80% of new power capacity to 2030 in the STEPS scenario, with solar PV alone accounting for more than half.

- A wave of new LNG export projects is set to remodel gas markets – starting in 2025, an unprecedented surge in new LNG projects is set to tip the balance of markets and concerns about natural gas supply.

- Affordability and resilience are watchwords for the future – diversification and innovation are the best strategies to manage supply chain dependencies for clean energy technologies and critical minerals.

- The world needs to go much further and faster, but a fragmented world will not rise to meet our climate and energy security challenges – proven policies and technologies are available to align energy security and sustainability goals, speed up the pace of change this decade and keep the door to 1.5°C open.

- Under today’s policy settings global emissions are on track to push temperatures up by about 2.4°C.

In his introduction, IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol said “The transition to clean energy is happening worldwide and it’s unstoppable. It’s not a question of ‘if’, it’s just a matter of ‘how soon’ – and the sooner the better for all of us.”

But then he added: “Governments, companies and investors need to get behind clean energy transitions rather than hindering them… claims that oil and gas represent safe or secure choices for the world’s energy and climate future look weaker than ever.” Surely, if clean energy is one-way, reliable, secure and affordable, governments and companies would not think twice, but get behind it and reap the benefits. So, what is holding them? The greatest challenge is security of energy supplies that gained prominence and focus after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, that renewables alone cannot provide.

Renewables are intermittent by nature and, on their own, cannot provide reliable energy. As their share in the electricity mix increases, substantial investment in grids is needed to make this work. The IEA estimates that achieving climate goals will require adding or replacing 80mn km of power lines by 2040 – an amount equal to the entire existing global grid. And until intermittency is overcome, renewables also require flexible back-up, preferably by natural gas and not coal.

Fossil fuels will peak before 2030

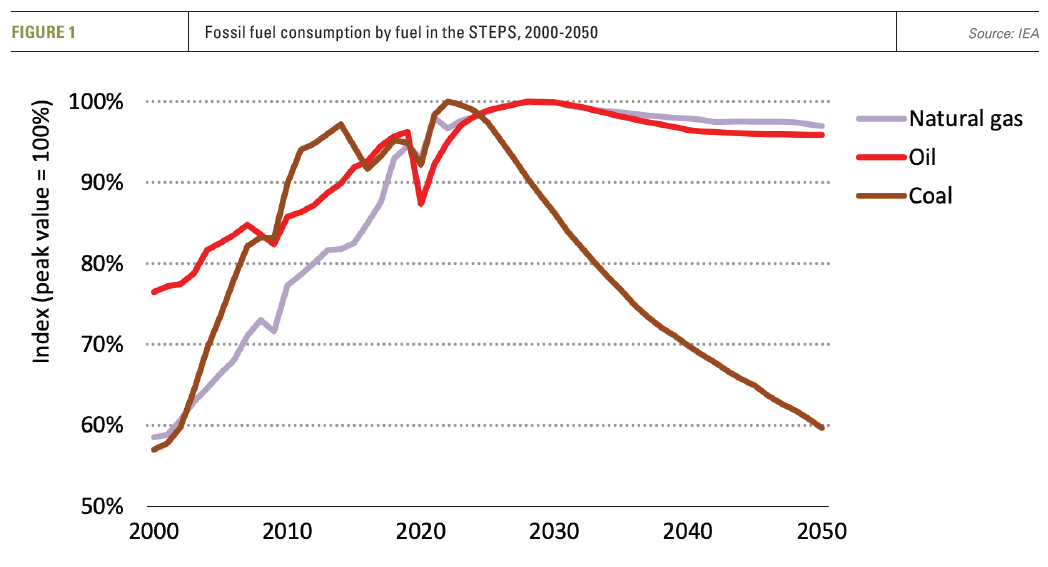

This was the most sensational conclusion in the outlook. IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), that provides an outlook based on the latest government policy settings, for the first time sees lower demand projections for each of the fossil fuels, such that oil, gas and coal are all projected to reach a peak by 2030 (see figure 1). Other scenarios, APS – and NZE-based on adjusting the models to achieve a prescribed end result – require a faster decline.

The IEA attributes this to the “energy system changing as low-emissions electricity and fuels meet an increasing share of the world’s rising energy needs, and as energy efficiency improvements help to moderate those needs.”

The IEA states that the scaling up of clean power is hastening the decline of coal consumption. Similarly, the “end of the internal combustion engine (ICE)” turns prospects around for oil. As for natural gas, the energy crisis has marked the end of the “Golden Age”.

Nevertheless, following consumption reaching a peak by the end of this decade, oil and gas demand do not fall significantly but remain more or less constant to 2050.

The IEA acknowledges that when it comes to oil and gas “energy security challenges will remain since the process of adjustment to changing demand patterns will not necessarily be easy or smooth.” As a result, “continued investment in fossil fuels is essential” in all of the scenarios.

The impact of economic growth in China

As the IEA rightly points out, China’s economic growth has defined the energy world in recent decades. Over the last ten years China was responsible for 34% of the growth in global GDP, 53% of global energy demand growth, 85% of the rise in energy sector CO2 emissions and 45% of global renewables capacity.

China is also a clean energy powerhouse, accounting for around half of wind and solar additions and well over half of global EV sales in 2022. But despite this, it has also been growing its consumption of coal, oil and gas. It is targeting to increase the share of natural gas in its energy mix from 8.5% in 2021 to 15% in 2030.

But, as the IEA is pointing out, its economy is changing, it is rebalancing. Given China’s size, this rebalancing could have substantial impacts on the outlook for its energy sector, but also for the world. According to the IEA, a key factor behind this is that “China’s working age population peaked around 2015 and is projected to fall by more than 20% by 2050. With this will come a reduced need for investment, such as in new housing and infrastructure.”

As a result, in order to reflect this, the IEA has revised downwards the long-term projection of GDP growth in China to just under 4%/yr for the period 2022 to 2030, and 2.3%/yr for the period 2031 to 2050.

Based on these, the IEA projects that slower GDP growth will result in China’s total energy demand peaking around the middle of this decade, followed by stable and then slowly declining demand. As a result, clean energy growth will be “sufficient to meet this, driving a decline in fossil fuel demand and hence emissions.”

Given the size of the Chinese economy, this has a huge impact on future global oil and gas demand, as the WEO 2023 shows. This is one of the key reasons behind IEA’s projection that demand for all fossil fuels will peak before 2030.

Natural gas

Natural gas markets have been upended by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The WEO states that the sharp reduction in pipeline supply to Europe tightened global gas markets, resulting in record high prices and a drop in global demand by around 1% in 2022. But this is set to recover to an average growth of 1.6% a year between 2022 and 2026.

The crisis prompted a scramble by gas importing countries around the world to secure supplies. This has boosted near-term prospects for additional investment, especially for LNG export and regasification projects.

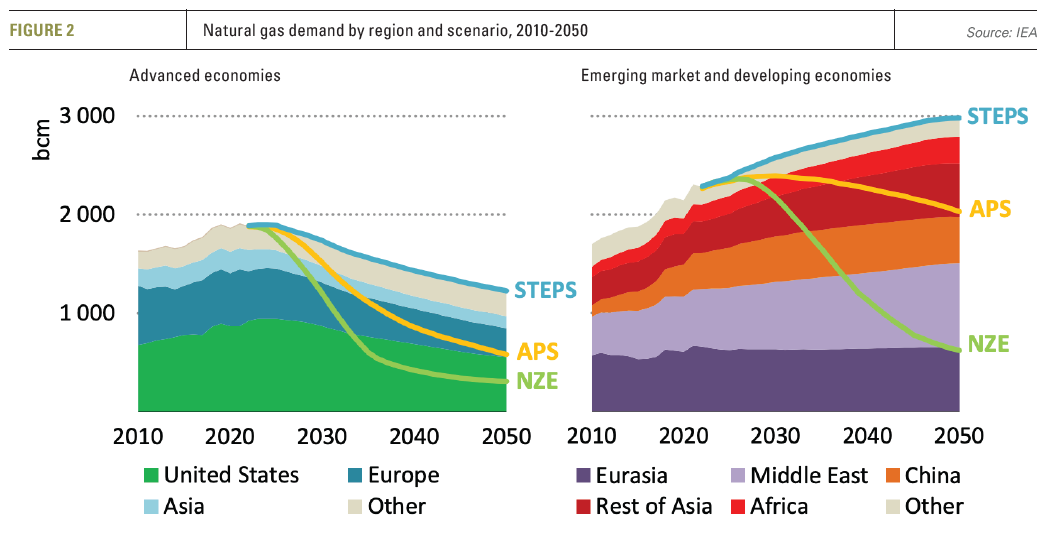

Even though the IEA projects flatlining of global gas demand after 2030, there is a huge difference in gas demand between advanced and developing economies (see figure 2).

Even though the IEA projects flatlining of global gas demand after 2030, there is a huge difference in gas demand between advanced and developing economies (see figure 2).

Gas demand declines in advanced economies in all scenarios. In STEPS it declines by 40% by 2050. Even though there is a continued need for natural gas to back-up variable renewables, the IEA states that this standby role requires much less consumption of natural gas than current operating plants as baseload supply, complemented by other options such as batteries and demand response.

In contrast, natural gas demand in emerging markets and developing economies increases by over 25% under the STEPS scenario. By 2030 ample new LNG supplies are anticipated, that could keep gas prices low and potentially stimulate demand growth. This explains the substantial differences among the three scenarios in Figure 2.

There will also be increasing demand for LNG. Two-thirds of globally traded natural gas will be delivered as LNG in the STEPS by 2030, up from a level of around 50% in 2021. The US will solidify its position as the world’s largest LNG exporter through 2030.

But, according to the IEA, with natural gas demand peaking in all WEOscenarios by 2030, there is little headroom remaining to grow beyond then. Global LNG markets look amply supplied in the STEPS scenario until at least 2040, putting at risk around two-thirds of LNG projects currently under construction in terms of fully recovering their initial capital investment.

Given the continuing pace of investments in new liquefaction plants in the US, and regasification plants everywhere else, clearly investors have a different view about the future of the industry. As is the oil and gas industry. Following the $53bn acquisition of Hess, Mike Wirth, CEO Chevron, criticised the IEA for forecasting that oil and gas demand will peak before the end of this decade, saying he did not think it was “remotely right… they can build models, but we live in the real world.”

Challenges and uncertainties

Clearly uncertainties abound.

The IEA states that its STEPS scenario presents results based on existing government policies. But they are also based on assumptions about the future growth of China’s economy, the pace of development of clean technology, the rate of EV penetration, and much more. In presenting and interpreting the results, this is often lost in translation. There are many uncertainties that challenge these assumptions. And key among these is that experience is that governments, notoriously, do not always deliver stated policies and climate pledges. Assuming they will do so in future is a big “if”.

This has major implications. By stating that fossil fuel demand is set to peak by 2030, the IEA is undercutting the rationale for any future rise in investment. But could that prove to be a dangerous development?

True, "the transition to clean energy is happening worldwide and it's unstoppable,” and that’s a good thing. But do IEA’s results in WEO stand up to scrutiny?

Even though global coal consumption is projected to have already started to decline rapidly, there is no evidence yet that it is about to happen. It has been rising by about 0.6%/yr, including in 2023, led by China and India. In China, in the first half of 2023, construction was started on 37GW of new coal power capacity, 52GW was permitted, while 41 GW of new projects were announced and 8 GW of previously shelved projects were revived. Despite this, the IEA believes that output from China’s coal-fired power plants will peak by 2025 and then start declining – difficult to believe.

India has 30.4 GW coal plant capacity under construction and about 35 GW in pre-construction. Indonesia says it will stop commiting to build new coal-fired power plants after 2023 in order to to meet its carbon-neutral goals, but it is already committed to building more than 100 plants – it will still be churning out CO2 decades after that.

Expected reductions in coal demand in advanced economies will not be sufficient to offset this. With such commitments already in place, and despite the rapid increase in clean power, it is difficult to see a rapid decline in coal consumption in the foreseeable future. Measures to reduce or phase-down coal consumption must be given priority.

IEA’s assumptions about China’s future economic growth are central to the its energy demand outlook in WEO 2023. It acknowledges that even small variations in these assumptions can have huge ramifications on China’s actual energy demand.

But already these are being challenged. The International Monetary Fund has just raised its China economic growth forecast to 5.4% for 2023 and 4.6% in 2024.

There is a plethora of forecasts beyond that, with many -especially the most reputable ones- expecting China’s average GDP growth to 2030 to be 4.5% and over 3% in the period 2031 to 2040. These are even higher than IEA’s assumptions in WEO 2022. Admittedly, there is considerable uncertainty in forecasting China’s GDP growth well into the future, but IEA’s current assumptions appear to be at the lower end of other forecasts. This could put into question many of the conclusions in WEO 2023, particularly those about peaking oil and gas demand this decade, with huge implications.

In an incisive article in the FT in September, well supported with charts and data, Martin Wolf argues forcefully that “We should not call ‘peak China’ just yet.”

The stark reality is that “the sheer scale of China's energy demand means that even though it is making vast strides to deploy renewables and electrify its vehicle fleet, it will still be consuming vast quantities of fossil fuels for decades to come.” In addition, rapid growth in energy demand means that, so far, renewable generation is not growing fast enough to meet it, let alone reduce the need for coal. And with drought becoming more frequent, severely reducing hydroelectric power, reliance on coal-fired power generation is likely to continue, even as renewable power continues to grow rapidly.

An additional factor is that in both China and India energy demand is likely to carry on rising fast for many more years as their populations aspire to reach the same living standards as people in the US and Europe and as both countries continue modernization.

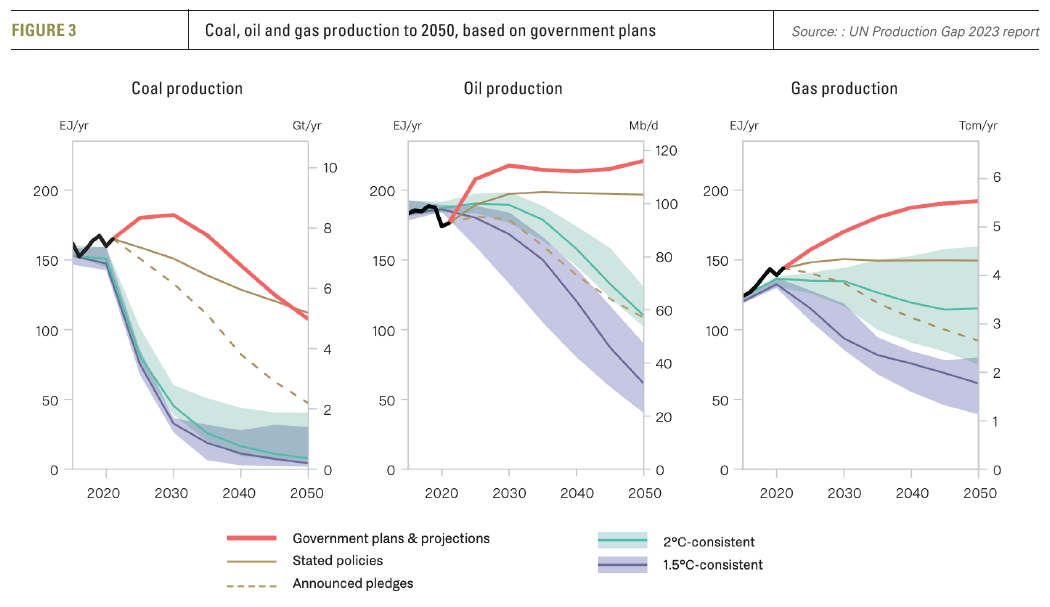

Another major challenge to IEA’s projections is the UN’s Production Gap 2023 report, published early November. It states that based on its assessment, government plans and projections would lead to an increase in global coal production until 2030, and in global oil and gas production until at least 2050 (see figure 3).

Based on this, oil production will carry on increasing beyond 2030 and then reach a plateau production of about 116mn barrels/day by 2050. This is comparable to OPEC’s forecast.

Natural gas production will carry on increasing and by 2050 it will be over 30% higher than now. This broadly agrees with the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) forecast of a 36% increase, but higher than BP’s Energy Outlook 2023 estimate of a 20% increase.

A new report from the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), published in October, shows global fossil fuel demand to hit record-high in 2024, with oil demand expected to increase by 1.7% and natural gas demand by 2.2%.

Clearly, future potential trajectories of global gas demand vary considerably among energy transition outlooks, introducing unprecedented uncertainty. Among these, IEA’s projections are particularly low. As the International Gas Union (IGU) points out, this could have important implications in influencing policy decisions, as supply will need to be developed ahead of demand.

What these illustrate is that continuous investments are needed in the natural gas value chain to cope with natural supply decline and likely growth in demand.

As the IGU recommends, comprehensive and balanced energy planning is needed to avoid further supply crises. Otherwise, the required natural gas supply may not be developed to meet demand resulting in heightened emission levels, if replaced by coal, and more energy crises. Without additional investment, gas production will decline by about 25% by 2030, with major implications on global energy balances and prices.

Figure 2 shows coal, oil and gas production levels consistent with 1.5°C and 2°C pathways. Clearly without drastic change, it is getting much harder to achieve these. That is why a rapid increase in the adoption of carbon capture and storage (CCS) is gaining high priority. This is expected to be one of the central themes at COP28, as well as a plan for responsible fossil fuel phase-down.

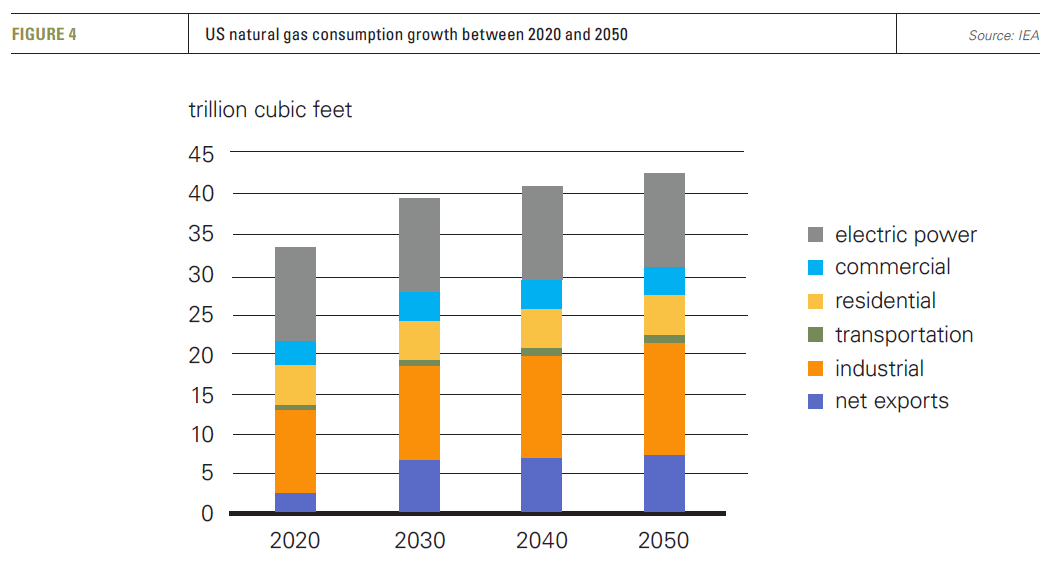

Even though gas demand in Europe may decline, partly as a result of losing its heavy and chemical industries to the US, it could be very different for the US. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) is projecting growth. It expects natural gas consumption in the US to grow by 25% between now and 2050 (see figure 4), mostly because of growth in demand for industrial use and exports.

Even though gas demand in Europe may decline, partly as a result of losing its heavy and chemical industries to the US, it could be very different for the US. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) is projecting growth. It expects natural gas consumption in the US to grow by 25% between now and 2050 (see figure 4), mostly because of growth in demand for industrial use and exports.

This is at variance with IEA’s projections in Figure 2.

WEO 2023 is designed to be a blueprint for policymakers, especially in setting up priorities to get the global energy transition back on track and aligned with net-zero by 2050. But in doing so it is necessary to ensure an orderly transition where the phase-down of fossil fuels and the speed of transition are driven by how fast the world can phase-up clean energy alternatives.

China has already warned, ahead of COP28, that countries must refrain from "empty slogans" divorced from reality and adopt a pragmatic attitude to climate change that reflects concerns such as energy security, economic development and growth.

Energy transition must be just and energy-secure, while simultaneously reducing emissions and driving economic growth. Reducing investment in and production of natural gas and oil, under the assumption that renewables can quickly replace them in all energy sectors, is prone to substantial economic and geopolitical risks.