IEA: low-emission hydrogen at risk [Gas in Transition]

Green hydrogen took centre stage at COP28 in Dubai, as one of the key technologies that has the potential to be a driver in powering the climate transition and play an important role in energy-intensive sectors such as chemicals, refining and steel.

But even though momentum behind green hydrogen continues to grow, cost pressures put its development at risk. In a report Global Hydrogen Review 2023, released in September, the International Energy Agency (IEA) is warning that without stronger political support, policies and regulations, future progress is at risk.

Lack of such support “is hindering investment decisions for planned projects whose economic feasibility depends on public support, a situation that has worsened due to the impacts of inflation.”

At COP28, the IEA and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) discussed policy support mechanisms that can stimulate demand for low-emissions hydrogen in hard-to-abate sectors. They warned that “without creating robust demand, low-emissions hydrogen producers will not secure sufficient off-takers to unlock large-scale investments and accelerate deployment.”

This was also the subject of the well-attended 4th annual Hydrogen Transition Summit held in Dubai during COP28 that included the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Its objective was “to drive the global hydrogen agenda, expedite the transition towards clean energy, and address the urgent climate crisis by embracing a hydrogen-based economy.”

In addition, the COP28 Presidency’s High-Level Roundtable on Hydrogen launched a number of initiatives to “accelerate commercialisation of hydrogen, to keep the 1.5oC target within reach and to unlock the socio-economic benefits of cross-border value chains for hydrogen and its derivatives.”

These led to the COP28 clean hydrogen declaration that was endorsed by over 30 countries, including the US, Germany, Japan and the COP28 host, UAE. It pledged to work toward “mutual recognition of certification schemes based on a new ISO methodology -launched at COP28- as a globally recognised standard that national schemes could adopt or maintain consistency with.” It calls for clean hydrogen to be prioritised for displacing fossil fuels.

The waters were muddied somewhat by a rival declaration at COP28. ‘The Joint-Agreement on the Responsible Deployment of Renewables-Based Hydrogen’, that pledged to “prioritise renewable hydrogen for displacing the current use of fossil-based H2 — produced from either coal or gas — or use it in hard-to-abate sectors where the molecule makes the most sense as a route to decarbonise.” It highlighted that “most use cases related to residential and commercial heating and power generation” potentially cannibalise renewable electricity and prevent a full transition away from fossil fuels.” Most of its signatories were NGOs, environmental non-profit organisations, trade associations and voluntary certification companies. They claimed that the ISO methodology to calculate greenhouse gas emissions is insufficient and “risks facilitating greenwashing practices by the fossil fuel industry.”

Given the challenges identified by the IEA, putting development of green hydrogen at risk, rival declarations at COP28, the most important energy transition event of the year, will not help and could make the situation even more challenging.

IEA’s Review findings

The key findings from IEA’s Review are:

- Efforts to stimulate low-emission hydrogen demand are lagging behind what is needed to meet climate ambitions.

- Transforming momentum around low-emission hydrogen into deployment remains a struggle despite strong political support.

- Low-emission hydrogen production can grow massively by 2030, but cost challenges are hampering deployment.

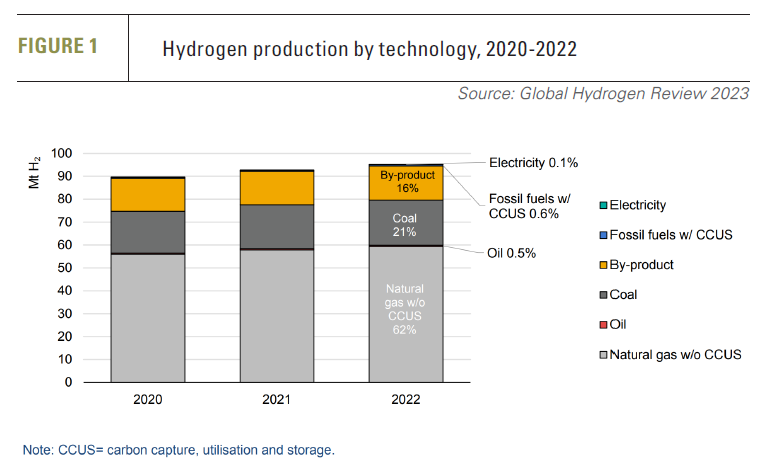

- According to the IEA, low-emissions hydrogen accounts for only 0.6% of overall hydrogen production and use to-date (see figure 1). Out of this, 0.5% is blue hydrogen, with only 0.1% green hydrogen produced by electrolysis.

In fact, global production of low-carbon and renewable hydrogen reached 0.7mt in 2022, compared with 70-125 tonnes/year required by 2030. There is a very long way to go.

Potential annual production of low-emission hydrogen could reach 38mn t (equivalent to about 120bn m3 natural gas) by 2030, if all announced projects are realised. However, only 4% of these have, so far, reached a final investment decision (FID). One reason is that developers wait for government support before making investments. The IEA has made recommendations -highlighted below- to speed up the process.

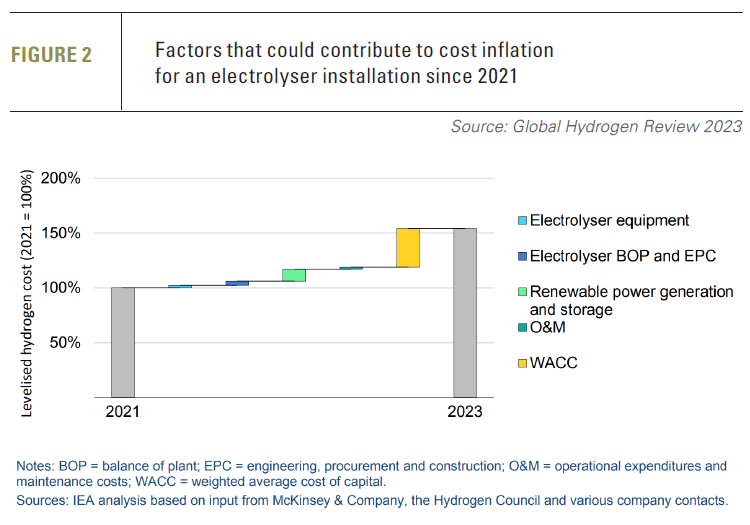

As a result of increasing capital and financial costs, due to high inflation, and supply chain challenges, equipment and financial costs are increasing, “threatening the bankability of projects across the entire hydrogen value chain, which are highly capital intensive.” This is “putting projects at risk and is reducing the impact of government support for deployment.” They have also impacted the cost of electrolyser installation that IEA estimates to have increased by 50% since 2021 (see figure 2).

Production levels can increase only if greater efforts are made on encouraging green hydrogen project uptake.

The IEA states that measures to stimulate low-emission hydrogen use have only recently started to attract policy attention, but are still not sufficient to meet climate ambitions. Efforts by the private sector remain at very small scale and demand signals from international cooperation are unclear.

The IEA states that measures to stimulate low-emission hydrogen use have only recently started to attract policy attention, but are still not sufficient to meet climate ambitions. Efforts by the private sector remain at very small scale and demand signals from international cooperation are unclear.

The IEA recommends that governments:

- Urgently implement support schemes for low-emission hydrogen production and use.

- Take bolder action to stimulate demand creation for low- emission hydrogen, particularly in existing hydrogen uses.

- Foster international co-operation to accelerate solutions for hydrogen certification and mutual recognition of certificates.

- Quickly address regulatory barriers, particularly for project licensing and permitting.

- Support project developers to maintain momentum during the inflationary period and to extend regional reach.

But until these happen, lagging policy support and rising cost pressures put investment plans for low-emissions hydrogen at risk globally.

IEA’s executive director, Fatih Birol, warned that a challenging economic environment is testing the resolve of hydrogen developers and policymakers to follow through on planned projects. “Greater progress is needed on technology, regulation and demand creation to ensure low-emissions hydrogen can realise its full potential.”

The Review found that another serious challenge is that “efforts to stimulate demand for low-emissions hydrogen are lagging behind what is needed to meet climate ambitions.”

As IEA chief energy technology officer, Timur Gul, said, "This confluence of factors is particularly detrimental for an industry that faces high upfront costs related to equipment manufacturing, construction and installation." IEA’s solution? To counter these obstacles, governments should urgently implement low-emission hydrogen support schemes combined with regulations.

Further, the IEA recommends “aiding developers during the inflationary period through interventions like loan guarantees, export credit facilities or public equity investment in projects.”

Challenges

According to IEA’s Review only about 1.5mn-t low-emission hydrogen projects have taken FID to-date. On this basis, it is unlikely that the EU will achieve its target to produce 10mt of renewable hydrogen and import a further 10mt by 2030.

With permitting and construction of a new low-emission hydrogen facility typically taking over five years, projects that do not reach FID by next year are not likely to be in a position to contribute to achieving the EU's renewable hydrogen targets.

An additional challenge is the vast amount of renewable electricity capacity and land needed to produce EU’s green hydrogen targets.

Producing 1mn t of green hydrogen per year requires on average a total 10 GW of electrolyser capacity and 20 GW of renewable electricity generation capacity. And it takes 20 km2 of land to set-up a 1-GW solar power plant.

On this basis, it will take 200 GW renewable electricity capacity and 4000 km2 land to produce 10mn t of low-emission hydrogen by 2030, and as much in North Africa to produce the equivalent amount of imports.

This is the same as the entire EU solar power capacity that stood at just under 200 GW at the end of 2022, with wind at 255 GW. North Africa’s entire solar power capacity is below 3.5 GW, with similar levels of wind power capacity.

The IEA and Bloomberg NEF estimate the global green hydrogen demand needed to achieve net-zero by 2050 to be about 500mt. Producing this would require 10,000GW renewable electricity capacity – three times as much as the global capacity now. And 200,000km2, just under the total land area of the UK.

The IEA is also warning that “The complexities of transporting low-emission hydrogen over long distances may result in a potentially higher carbon footprint compared to natural gas, if the energy inputs required to transport hydrogen are not decarbonised.”

Given IEA’s Review findings, the enormity of the challenge is obvious.

There are also questions about how climate-friendly hydrogen is. It is leak-prone and in its raw form it can cause chemical reactions that trap heat in the atmosphere. A study by EDF in 2022 explained “how unchecked hydrogen emissions can severely undercut the climate benefit of switching from fossil fuels to hydrogen.” It found that “if it is not done right, using hydrogen could be worse for the near-term climate than the fossil fuels it would replace.”

Gul compared the deployment of green hydrogen production to that of solar pv. He said solar pv first entered the markets in the 1980s, and “only reached around 1% of global power generation capacity in 2015, before becoming the leading low-cost power generation source in many parts of the world as it is today.” He added that green hydrogen production is 10-15 years behind solar PV. On that basis it will be well into the 2030s before green hydrogen starts making inroads into natural gas demand. Current trends tend to support that.

Competition to natural gas

All major European countries are targeting increased amounts of low-emission hydrogen to replace natural gas by 2030 and beyond. But is this achievable?

IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2023 states that for low-emissions hydrogen “the near-term outlook is clouded by cost inflation, uncertainty around policy details and supply chain bottlenecks. In Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), 7mn t of low-emissions hydrogen is produced globally in 2030, most of which replaces existing supplies of hydrogen for ammonia plants and refineries. In the Announced Pledges Scenario (APS), low-emissions hydrogen demand reaches 25mn t in 2030.” Given existing industry needs for hydrogen, such quantities -even if achieved, which is a challenge- will not impact natural gas demand.

The premium of green hydrogen over natural gas is already high. The Platts Hydrogen Price Wall, that reports regional price differences and month-on-month changes, shows that “the cheapest clean hydrogen production globally was in the Northeast US in August, averaging $2.30/kg for alkaline electrolysis, compared with below $1/kg for unabated gas-based production in some regions.”

With LNG and natural gas prices expected to drop further after 2025, as a result of the massive expansion in global LNG production capacity by then, the price differential with green hydrogen will increase even further.

The IEA states that low-emission hydrogen has the potential to compete with natural gas in all potential applications. In existing hydrogen applications, it often competes with hydrogen from unabated reforming of natural gas. But based on price differences and the challenges green hydrogen faces, it will take a long time before green hydrogen can seriously compete with natural gas.