IEA hails Age of Electricity [Global Gas Perspectives]

The International Energy Agency (IEA) published its annual World Energy Outlook (WEO-2024) on October 16, warning that the world is failing to limit global warming to 1.5°C. Under its Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), it estimates the world is heading towards 2.4˚C by 2100, showing no improvement since 2023.

What is new this year, though, is the declaration by the IEA that the world is now “moving at speed into the Age of Electricity, which will define the global energy system.” Its executive director Fatih Birol said “it is clear that the future of the global energy system is electric – and now it is visible to everyone.”

The main findings of the WEO-2024 are:

-

Geopolitical tensions and fragmentation are major risks for energy security and for coordinated action on reducing emissions.

-

Robust, independent analysis and data-driven insights are vital to navigate today’s energy uncertainties.

-

Geopolitical risks abound but underlying market balances are easing, setting the stage for intense competition between different fuels and technologies.

-

Clean energy momentum remains strong enough to bring a peak in demand for each of the fossil fuels by 2030.

-

Demand for electricity is taking off.

-

The rise of electric mobility, led by China, is wrong-footing oil producers. Over one in two cars sold globally in 2035 are set to be electric (EVs).

According to the IEA energy security remains a key issue and is inextricably linked with climate action. But despite the growing momentum behind transition to clean energy, the world is still a long way from achieving its net zero goals.

WEO-2024 warns that without a change to today’s policy settings, the world is on course for a rise of 2.4°C in global average temperatures by 2100, well above the Paris Agreement goal of limiting this to 1.5°C.

The Age of Electricity

The IEA states that the world is set to enter a new energy market setting in the coming years, fraught by continued geopolitical problems but also by the relatively abundant supply of multiple fuels and energy technologies. After the Age of Coal and Age of Oil, the world is moving rapidly into the Age of Electricity. “Electricity has recently grown twice as fast as total energy demand. But from now to 2035, it is set to grow 6-times as fast, driven by EVs, air-conditioning, chips, AI and others.”

But despite IEA’s assertions, peak oil, gas or even coal still eludes the energy transition.

Also, electricity growth is very unevenly spread. WEO-2024 estimates that two-thirds of the global increase in electricity demand over the last ten years has come from China, while in Europe electricity demand has been declining.

The IEA recommends that as a result of this transformation, “a comprehensive approach to energy security needs to extend beyond traditional fuels to cover the secure transformation of the electricity sector and the resilience of clean energy supply chains.”

This will require substantially increased investments in new electric energy systems, particularly power grids and energy storage that currently account for 60% of spending on renewable power.

The Age of LNG

The IEA states that global LNG export capacity will increase by about 50% by 2030, led by the US and Qatar. Even though some of the announced projects are facing some delays, as much as 270 bn m3 is expected to enter the markets by 2030 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: An increase of nearly 50% in global LNG export capacity is on the horizon

.png)

Source: WEO-2024

Growth in demand will be led by China, India and Southeast Asia.

Under its STEPS scenario, the IEA sees global LNG demand growing in the period to 2035, and with supply exceeding demand – creating an LNG glut – LNG prices will come down. These are likely to remain low over the next decade, with the risk of crowding out renewable energy development in different parts of the world, especially in Asia and Africa.

But the IEA warns that “gas-importing emerging and developing economies would generally need prices at around $3 to $5/mn Btu to make gas attractive as a large-scale alternative to renewables and coal.”

Global natural gas demand

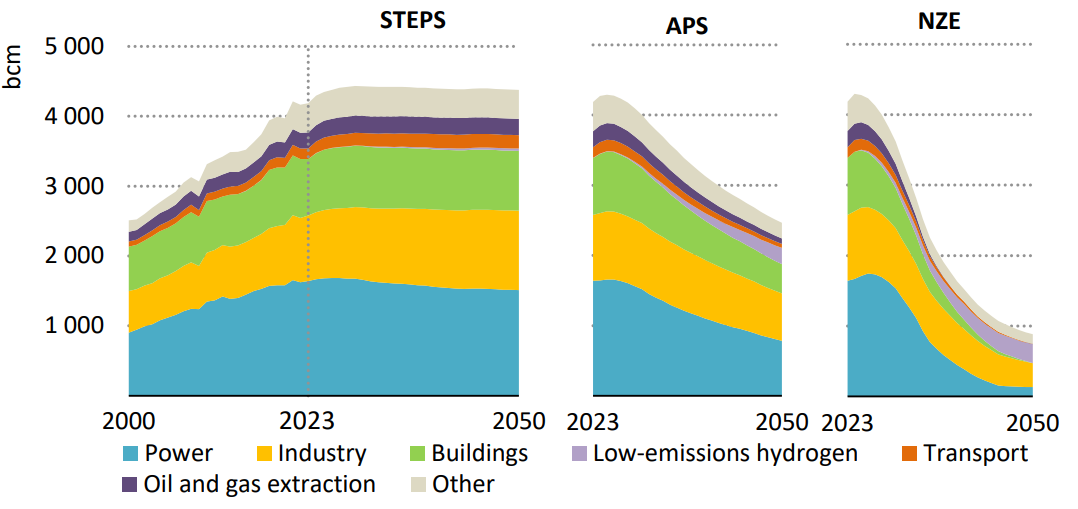

Natural gas demand has been revised upward in all IEA scenarios compared with WEO-2023, reflecting stronger anticipated demand for gas to meet growth in electricity demand in China as well as additional demand in the Middle East. But despite this, and after decades of growth, the IEA expects natural gas demand to plateau by 2030 under STEPS and fall 40% in the APS and by 80% in the NZE Scenario by 2050 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Natural gas demand by sector and scenario, 2000-2050

Source: WEO-2024

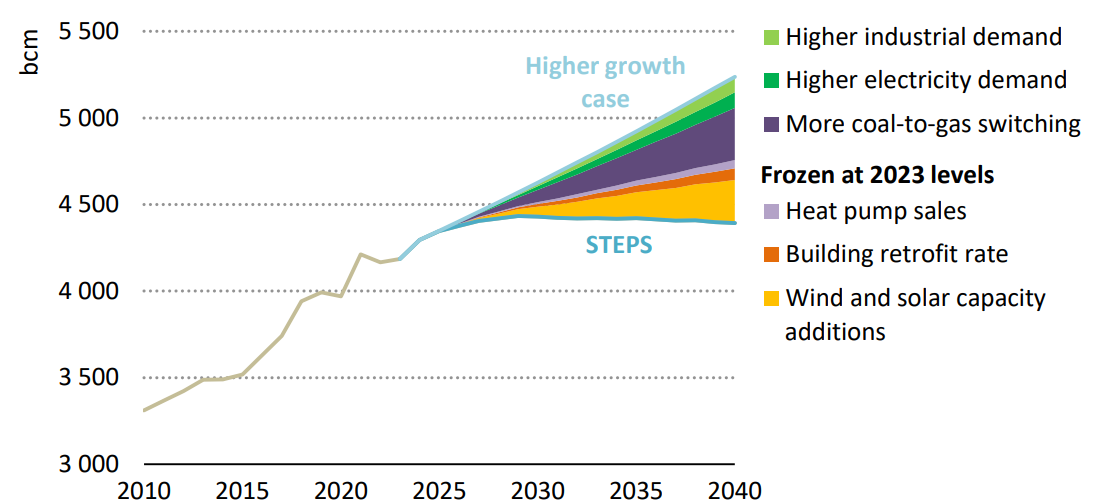

Even though its STEPS scenario expects global natural gas demand to peak by 2030, the IEA is hedging its bets. It recognises that changes in global energy demand could enable global natural gas demand to carry on growing at the pace seen over the past five years. These include higher demand in industry, inability of renewables to meet primary energy and electricity demand growth, coal-to-gas switching and slower growth in wind, solar PV and heat pump capacity than envisaged by STEPS.

The IEA also recognizes that “natural gas can also provide flexibility to integrate variable renewables, and this is often highlighted as a reason for its enduring role in transitions.”

Should these factors materialise, demand could rise to as much as 5,200 bn m3 by 2040, or nearly 850 bn m3 higher than in the STEPS scenario (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Factors that could lead to continued natural gas demand growth above the levels of STEPS, to 2040

Source: WEO-2024

The IEA agrees that “more favourable long-term circumstances for growth in natural gas demand cannot be ruled out, but they depend on a combination of policy settings, technology developments and market trends.”

Under such circumstances, and with global primary energy demand likely to carry on growing beyond what STEPS envisages, clearly the world must maintain investment in the development of new gas projects.

Challenges

The main highlight of WEO-2024 is IEA’s assertion that the world is “now moving at speed into the Age of Electricity.” Even though this may happen eventually, is it actually happening now “at speed?”

Let's look at recent historical data and trends. According to Energy Institute’s Statistical Review of World Energy 2024, global primary energy consumption grew on average by just over 1%, or 5.2 EJ/year between 2013 and 2016. But it more than doubled during the next three years to 2019, growing by over 2% or 12 EJ. Following the hiatus of COVID-19 and the invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022, global primary energy consumption has now returned to the same rate of growth. There are no signs of slowing down.

Throughout this period electricity generation grew by an average of 2.5%, including more recently, in the period from 2021 to 2023. In 2013 it comprised about 16% of global primary energy and by 2023 this increased to just over 17%. At this rate, energy transition will be a long-drawn process.

In 2023 fossil fuels contributed 81.5% of global primary energy, only slightly down from 81.9% in 2022.

These data alone do not substantiate IEA’s “at speed” claim. At these rates of growth, it will take some time before the world convincingly moves into an “Age of Electricity.”

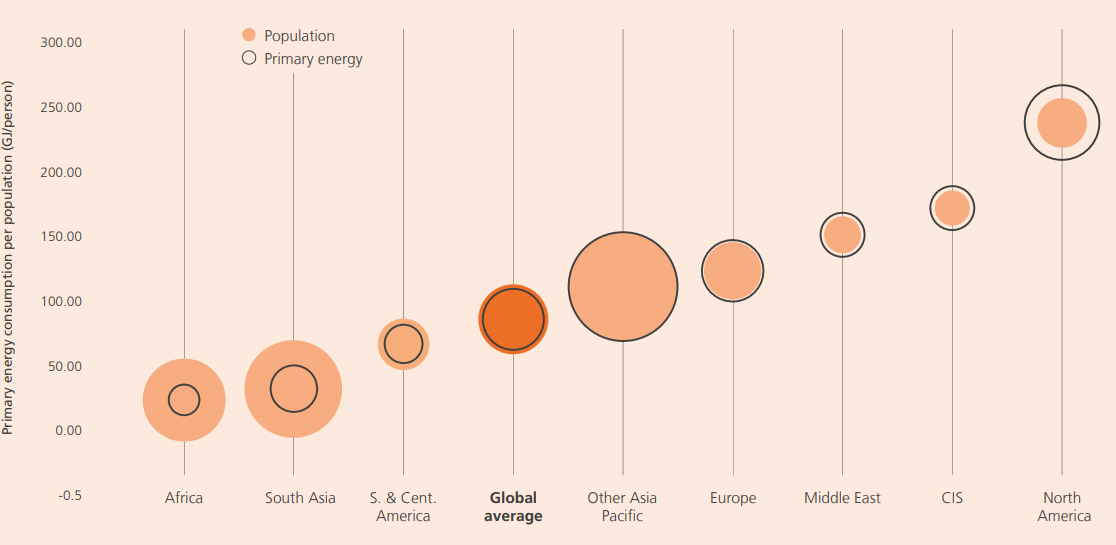

While this is happening, global primary energy demand will keep increasing. This is driven by the growth in the world population, expected to increase by 20% by 2050, impacting energy demand. In addition, at present in Africa, South Asia, and South & Central America, the average amount of energy consumed/person is about 30 GJ, less than 40% of the global average (see Figure 4), even though their combined population is over 50% of the world population and is growing at a faster rate. Not only this is likely to approach 60% of the world population by 2050, but, with improving standards of living, their energy consumption will also approach the world average.

Figure 4: Primary energy consumption per capita per world region

Source: Energy Institute's Statistical Review of World Energy 2024

Energy consumption per capita has actually been decreasing in OECD countries, by about 0.7%/year over the last decade. But it has been increasing in non-OECD countries -that comprise 83% of the world’s population – at a rate of 1.4%/year and faster more recently. In India, where energy consumption/capita is only 16% of the OECD average, the rate increase is even faster, at 3.2%/y.

The combined effect of all these factors could be a 30%+ increase in global primary energy demand by 2050. Should this happen all forms of energy will need to carry on increasing to provide it, with energy security remaining a key issue.

As McKinsey points out, “despite the progress made by renewables, they are not growing fast-enough to keep-up with the growth in global energy demand resulting from improving living standards and growing energy needs.”

This is one of the reasons why OPEC, oil and gas majors, and now major international banks and lenders, believe that abandoning investment in new oil and gas will destabilise the energy markets and lead to further crises.

Provided it is understood that IEA’s projections are based on scenarios to achieve targeted end results, these can be used as a source to inform future policies and strategies. The STEPS scenario assumes that country prevailing policy settings will be adhered to and APS that announced pledges, targets and net-zero goals made by governments will be met in full, while NZE maps a path to lead to net-zero by 2050. As such, the results in WEO-2024 are the outcomes of scenario modelling rather than fact-based or forecasts. IEA’s focus is on accelerating energy transition.

But, as McKinsey research shows, despite recent momentum, the energy transition is at an early stage. It highlighted a potential disconnect between climate ambitions and what is likely to be achieved in practice. “Right now, we're only at about 10% of the deployment of ‘physical assets’ – technologies and infrastructure – that we will need to meet global commitments by 2050.”

The current trajectory will not achieve net-zero this century. In fact, according to a recent UN Environmental Programme (UNEP) Emissions Gap Report, “the world is on course for a temperature rise of more than 3˚C above pre-industrial levels.”

The problem is that, so far, most countries for various reasons do not adhere to their declared policies and climate pledges. A key factor in most of Africa and the Global South is lack of funding. The IEA is warning that “financing costs and project risks are limiting the spread of clean energy.”

The recent failure of COP16 to agree funding to protect biodiversity does not bode well for the much more ambitious New Collective Quantitative Goal (NCQG) on finance that needs to be agreed at COP29 in Baku.

The world is not sticking to its climate stated policies

A recent analysis by the Berlin-based Mercator Research Institute concluded that the vast majority of climate policies and political efforts at tackling climate change have little effect. It found that “out of 1500 climate policies implemented between 1998 and 2022 in 41 countries only a slim minority have led to a significant reduction in carbon emissions, with most policies being too specifically targeted to make a substantial difference.” Only 63 of the 1500 policy interventions actually produced an appreciable reduction in carbon emissions.

This is both because countries are not making ambitious-enough promises and because the policies they put in place often do not work as well as planned.

A UN committee reported in October that with only six years remaining to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the world is on track to achieve only 17% of targets. Nearly half the 17 targets are showing minimal or moderate progress, while over a one-third are stalled or going in reverse. Identified obstacles that have contributed to this include the COVID-19 pandemic, escalating conflicts, geopolitical tensions, climate change impacts and systemic economic shortcomings.

The report highlighted the need for financing for development as the foremost priority. The investment gap in developing countries is $4 trillion/year. “It is crucial to rapidly increase funding and fiscal space, as well as reform the global financial system to unlock funding.”

Assessment in 2023 of countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – pledges to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – concluded that “these plans are not likely to result in change rapid and impactful enough to alter the world’s trajectory for the next few years or decades.” A reason behind this is the Paris Agreement’s focus “on the ambition of targets and global pressure on countries to announce a date for achieving net-zero emissions, that has outstripped countries’ realistic pathways to achieve those targets, which will require significant economic and social change to deliver.”

There is also a disconnect between the interests of developing and developed countries. For most developing countries, “adapting to the ongoing, increasingly severe, impacts of climate change is far more urgent than reducing greenhouse gas emissions.”

Even though renewables have great potential, they are still facing problems like storage, grid management and the inability to produce power on demand during peak hours. This is a challenge for power utilities whose priorities are “to ensure that the power supply is stable, reliable and affordable in order to guarantee both access to power for consumers and also support ongoing economic development.”

These are the reasons why the IEA's scenarios are useful “as a source to inform future policies and strategies,” and not as predictions of future outcomes. They cannot be considered as forecasts, that are usually the result of analysis of available past data and information to predict a future outcome.