[NGW Magazine] Hurdles for Indonesia's Mini-LNG

Indonesia's attempts to attract investors into its potentially ubiquitous small-scale LNG sector have not been crowned with success so far, as the pricing system works against small projects. But with new policies the landscape could be very different.

Indonesia is trying to attract companies to its fledgling small-scale LNG development sector amid a trend in the region for more small-scale LNG projects.

Last September, Keppel Offshore & Marine and Pavilion Gas, both Singapore-based companies, reached a heads of agreement with Indonesian state-owned generator Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) to examine the development of small-scale LNG deliveries to remote islands and locations in western Indonesia.

The agreement calls for the use of floating and onshore terminals and small-scale LNG carriers. Indonesia will use the gas to generate electricity at PLN power plants that range in size from 25 MW to 100 MW.

Tokyo Gas, Japan’s largest gas utility, also recently launched a plan to build LNG regasification terminals in the Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia. A report in the Nikkei Asian Review said Tokyo Gas will install small LNG storage and power-generating plants on remote islands around the region, supplying them “once a week or so,” using small LNG carriers.

Moreover, oil majors are also expressing interest in small-scale development in Indonesia. Last month, Anglo-Dutch major Shell’s executive vice-president for global energy marketing and shipping Steve Hill said that Shell would be "very keen" to participate in the small-scale LNG industry in the country once the government has put in place the structure to support its development.

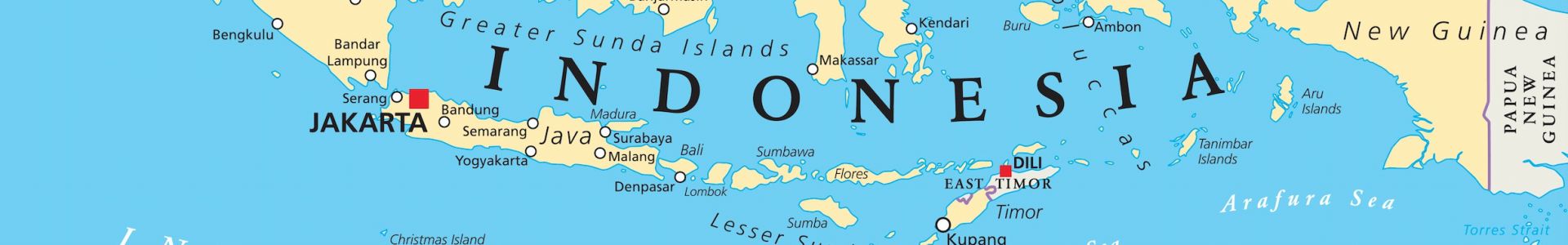

For its part, small-scale LNG offers a viable option to supply energy for Indonesia, an archipelago of more than 17,000 islands. Small-scale LNG development can help needed fuel reach the country’s so-called stranded markets, which are too far from existing gas pipelines, but are also not economically feasible for pipeline extension or new pipelines. To date, diesel is usually used to power most of the small power plants in these hard-to-reach places.

At the moment, Bali has the sole small-scale LNG project operational in Indonesia, though there are several other projects that are in the tendering process: Central Indonesia (ten locations in the southern part of Sulawesi and Nusa Tenggara), Bangka-Belitung-Pontianak (in the eastern part of Sumatra and West Kalimantan), Gorontalo (North Sulawesi) and Papua (five locations in Sorong, Manokwari, Nabire, Biak and Jayapura).

Indonesia’s small-scale development also comes amid projections that the country will turn from an LNG exporter to a net LNG importer by 2022, according to Fitch Group’s BMI Research. This is due to GDP growth, electricity demand growth of around 9%/yr, and maturing gas fields.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) said earlier April it expects the Indonesian economy to expand by 5.3 % year-on-year in 2018 and 2019 on the back of rising investment and rising household consumption. Indonesia, a country of some 260mn people, is the largest economy in southeast Asia and its most populous.

Strong small-scale potential

Edi Saputra, a specialist in Asia-Pacific gas and power at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie, told NGW that Indonesia has strong potential for small-scale LNG, particularly outside Java and Sumatra.

“In the islands and regions of Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Nusa Tenggara, Maluku and Papua, grid interconnections are sporadic and most demand centres are isolated,” he said. “Distributed power generation is a good solution for these markets, with small-scale LNG providing the fuel.”

However, despite these benefits, problems remain for companies that want to enter Indonesia’s small-scale LNG sector.

“The biggest challenge is the incompatibility between high infrastructure costs and current domestic pricing.” Saputra said. “There's a direct relationship between the costs of small-scale LNG and the size of the demand. The smaller the demand, the more expensive it is per unit of regasified LNG. Power plants in the existing Indonesian projects range from as small as 10 MW to as much as 500 MW. Projects below 40 MW are too small to be economic on their own.”

He said that LNG regasification projects in Indonesia are subject to a regulated price ceiling. “The price of regasified LNG at the power plant gate is capped at 14.5% ICP (Indonesian Crude Price/barrel). This equates to $8.7/mn Btu at an ICP price of $60, including the regas costs. Most small-scale LNG projects will not be able to meet this ceiling.”

The answer to this problem, Saputra says, is for the government to scrap the price cap for small-scale LNG projects. Otherwise the projects will become non-bankable as the ceiling is insufficient to cover the costs. “The price differential between diesel and LNG is a better benchmark, to ensure that small-scale LNG will really deliver economic benefits,” he added.

Break-bulk capacity

Singapore, which is being touted as southeast Asia’s premiere LNG trading hub, could also help by delivering smaller LNG cargoes to Indonesia. In January, Singapore LNG Corporation (SLNG) announced that it was modifying one if its jetties at Singapore’s LNG terminal to support project growth in small -scale LNG development in Asia.

The Singapore-based Business Times said the move will allow the jetty to accommodate smaller vessels, with capacities ranging from 2,000 to 10,000 m³, instead of larger vessels ranging from 60,000 to 250,000 m³.

Singapore is equipping its SLNG terminal with break-bulk capability, Saputra said. “Indonesia could send its LNG in a conventional 138,000 m³ vessel and receive the smaller parcels to feed the small-scale regas projects. This will eliminate the need to build an additional intermediate hub, particularly for small-scale LNG projects in the western part of the country.”

However, breaking cargoes is not a cure-all for small-scale LNG since volume is lost when shipments are broken up. Another problem with small-scale LNG stems from the use of small vessels with limited regasification capacity. Locations with greater user demand will need several small volume cargoes to make up just one regular LNG cargo.

Saputra added that companies can also make projects 'less small' by improving project economics. Clustering several demand centres, and expanding further downstream to reach not only power plants but also industrial off-takers, could increase project size and reduce the unit costs, he said.

This requires demand aggregation with other emerging segments such as LNG into mining, bunkering, LNG trucking and retail.

Tim Daiss