How low can Britain’s Grids go? [NGW Magazine]

It is a risky time for investors in the UK’s gas infrastructure.

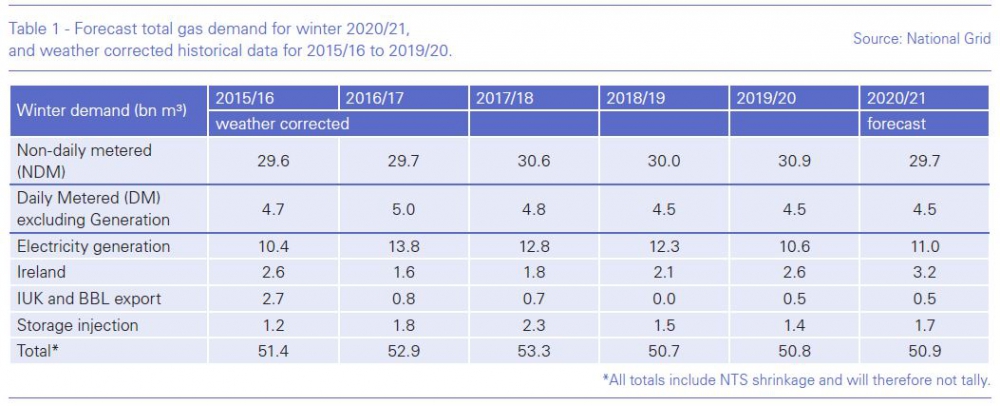

The background is one of falling demand for large-scale power generation – the system operator’s prediction of a small uptick this winter, driven by record low prices, only serves to illustrate the overall decline (see table).

Gas remains key for domestic heat load (around 80% of homes are heated by gas), and increasingly for gas engines, connected to the low-pressure network, but the UK has a target for net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, enshrined in legislation. That puts unabated gas firmly in the ‘out’ tray. Low-carbon hydrogen is among the options for replacement but it – and other solutions – require enormous and risky investment in the next few years.

Decisions on when and how to make that investment have added extra complexity to the regular review of network prices which is now under way – and which presents its own challenge to ‘pipe and wire’ investors who typically prefer a low risk environment.

The price review is the framework used by the independent regulator, Ofgem, to agree outputs and revenues for electricity and gas networks in Great Britain (Northern Ireland has its own utility regulator).

Usually on a five-year basis, each network submits a business plan to the regulator, meeting safety, quality, customer and regulatory requirements and seeking permission to charge certain revenues. The regulator responds generally by telling the companies to do more for less, and after some debate with the companies it issues a Final Determination (FD), which also sets the return companies can make on their asset base.

GB has high- and low-pressure networks and electricity transmission owners are in head to head arguments with Ofgem on the so-called RIIO 2 period – five years from April 2021 (electricity distribution networks’ process lags by a year). This price review is particularly fraught with risk for investors, and although in theory it will be all settled by FD in December, in practice uncertainty could last months or even years longer.

RIIO 2 has proved a particularly contentious price review. The previous review – dubbed RIIO 1 – broke the mould. Instead of simply seeking to lower costs, it had a new format that gave companies incentives for meeting targeted outputs that would be needed in a low-carbon world. An eight-year settlement was intended to give them longer-term visibility and hence cut costs.

The RIIO format was widely welcomed and Ofgem alumni have made presentations on it to many other regulators. But Ofgem was too generous in its incentive regime, which resulted in big pay-outs for all the companies, instead of rewarding the best.

Ofgem more or less admitted its error at a planned ‘check in’ after four years, when it considered re-opening the price review entirely. It concluded that the damage that would cause to the UK’s reputation for stable regulation outweighed the benefits it could claw back for consumers. But that gave in consumer watchdogs four years to bang the drum about how shareholders were making high returns at the expense of consumers and set up a clash in this year’s price review.

The regulator has to take a very tough line on company revenues and spending, while enabling huge investment in Net Zero investment. In addition, it has its own agenda on increasing competition to address.

The regulator has tried to solve this problem by slashing companies’ baseline spend and ring fencing most net-zero investment into so-called uncertainty mechanisms (aptly shortened to UMs) or reopeners. It all adds up to a very uncertain environment for the companies and investors.

National Grid told investors in September that the present draft was unacceptable. It “would increase the risk profile of its networks, jeopardise the UK’s transition to net zero and dampen innovation through lower returns.” It said the baseline return was lower than comparable for its European peers; that the business plan penalties were unjustified; and the risks outweighed the rewards.

The hydrogen option

Ofgem has dealt with networks’ investment in net zero options by shifting almost all the spend into UM, saying: “This is exciting work, but it will not be ready to progress in time for our FD in December.” It says this approach will allow the companies to ask for money as it becomes justified during the next few years.

UM would cover major investments to enable conversion of the gas network to carry hydrogen instead of natural gas – projects such as:

- An experimental hydrogen network in the northwest that would initially supply local industry (HyNet)

- Testing high levels of hydrogen in the existing network in Leeds (HyDeploy)

- Ensuring the high-pressure gas network can accommodate hydrogen.

A successful outcome to those trials could in fact see an increase in gas use in the UK, as the current assumption is that hydrogen would largely be produced from natural gas using steam reformation (with carbon capture and storage). And as some still argue that full electrification is a better option, the stakes are high for gas network owners.

The potential investment is huge: these projects are well past the research stage and the industry says large – read expensive – trials are the next stage. Ofgem says the UM approach “potentially covers up to £10 ($13)bn of investment that companies have signalled may be needed to facilitate the transition to net zero. This compares with Ofgem’s proposed baseline total expenditure allowance of £8.7bn for gas distribution companies and £7.5bn for transmission companies.”

Consumer watchdogs who do not want to see investments stranded have agreed with this approach and so, up to a point, have companies. But the companies have concerns.

The problem is that while they are happy to see the investment ring-fenced, they need a simple, speedy and predictable route to the spend. Ofgem, however, has proposed a complex suite of measures that include:

- Re-openers in response to changes in government policy on heat

- A Strategic Investment Fund with ‘essentially unlimited’ funding - but only for projects that fit into a planned series of cross-industry ‘challenges’ to be set under the direction of a net zero advisory group

- Relatively minor projects funded from a Network Innovation Allowance as part of the baseline.

What is more, Ofgem still has to set out details of how the projects will work and it is detail that companies require: for example, National Grid Gas Transmission (NGGT) feared that its projects would not fit any of Ofgem’s funding streams and gas distribution network Cadent pointed out that it needed to assure funding for the HyNet project quickly, in order not to lose match-funds from other sources.

National Grid Electricity Transmission considered that the suite of measures was “inflexible, bureaucratic in design and adds delays of 12-24 months to project delivery” at a time when action is urgent.

And there is a gap in funding: all the companies want to know how they can recoup the cost of developing projects to the point that they can use the UM. This and other investment (see below) is likely to be handled with ex-post assessment by the regulator. But it leaves companies facing cash flow issues and uncertain how much will be recovered – and it may hike consumer bills

unexpectedly if large costs are recovered in arrears.

Cutting the baseline

Having removed net zero investment from companies’ ‘baseline plans’, Ofgem has cut back hard on the remainder. In its draft determination (DD) it proposed to make dramatic cuts in planned expenditure on repair and replacement of pipes and wires. Ofgem said, “We’ve proposed to remove £8bn from network company spending plans where they have not presented value for money for consumers,” a cut of more than a third, bringing spend across the networks down to £15.2bn.

It was especially tough on NGGT, which said the draft determination cut its baseline allowances by over 40%, from £2.60bn to £1.53bn. It said that reducing annual allowances in areas including asset health by 37% would mean the risk of network outages would rise by 19% and the company would be unable to meet all its legislative requirements to meet demand.

Ofgem has a logic behind its tough line on gas networks: it says the amount of gas being delivered is falling. NGGT and its low-pressure counterparts are not so sure. Although there are some customers disappearing – large gas turbines, for example – networks argue that peak volumes are increasing – sometimes driven by fleets of new gas engines starting up in low pressure networks to balance variable renewables.

And NGGT has been warning shippers for years that changed use has in practice meant large swings in demand that require it to be able to move gas more quickly, even within-day, rather than a predictable fall in volumes.

In fact, the regulator is taking almost as tough a line with electricity transmission networks, which are expected to expand with the commissioning of gigawatts of new renewable generation over the next five years. Scotland’s SSEN complained of “33% of unjustified cuts to our baseline allowances”.

The regulator also announced that it planned to halve the allowed cost of capital for networks and even proposed a backstop measure – which it dubbed the ‘out-performance wedge’ – that allows it to reduce the allowed equity return to reflect its expectations that companies will outperform the targets that it sets. NGET described the measure as “conceptually and practically flawed”.

Along with net zero uncertainties and cost cutting, Ofgem also wants to move forward on long-standing plans to increase competition in the energy networks business. It wants to ensure that all large, separable new network assets are opened to competition for ownership, using the model it has employed for offshore wind farm connections. As with net zero projects, the companies want to know how they will be funded to develop these projects up to the point of tender.

What now?

The price determination is always to some extent a negotiation between regulator and companies and the networks have pushed back hard on Ofgem’s proposals. Ofgem has given some ground, admitting to process and modelling errors, although it insisted that these amounted to just a couple of percent of the companies’ spend.

The companies also gained some powerful ammunition from the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the appeals body in price reviews. The CMA published preliminary findings in appeals over price settlements by four water companies and said Ofwat, Ofgem’s counterpart in the water sector, had been too harsh in setting the allowed cost of capital. The sector is seen as an important comparator for energy networks.

The companies and Ofgem are locked in discussions until December, when the regulator will publish its FD. At that point, companies have to accept the decision or appeal to the CMA, which may be costly and carries no guarantee of a positive outcome. This year that process could be more difficult: because of Covid the regulator wants to take up to three months of extra time to publish its FD, compressing the fixed period allowed to appeal.

The companies, meanwhile, have to put their business plans into action in April regardless. Investors can only sit it out until the smoke clears and they are able to decide whether to retain their investment. That will be well into 2021.

|

WINDLESS DAYS BODE ILL FOR SUPPLY Windless, frosty days with few hours of sunshine meant that gas provided 53% of the British power mix as NGW went to press, while coal added a few percent but less than solar and wind while nuclear was about twice solar at 15% of the 40 GWh demand according to Gridwatch (November 5, 16.00). National Grid issued severe warnings of low margins, although in October it had said there will be adequate power and gas supply for this winter. Some analysts have doubted this confidence. Energy trader Hartree Solutions said higher continental power prices imply a 99.7% risk of black-outs in the UK as interconnectors export power. Partner Adam Lewis told NGW that if the French nuclear plants suffer outages there could be times when UK and France are competing for the same megawatts. “In that instance you are probably in the nuances of one capacity mechanism versus another,” he said. National Grid said in its winter outlook for gas that it sees deliveries of LNG continuing unabated although since then, higher prices in Asia are drawing more cargoes. LNG can supply 145mn m³/d, even more than the UK continental shelf (123mn m³/d) or Norway (116mn m³/d). There are also two pipelines linking the UK to the continent that are price-responsive. “We anticipate volumes to be as high this winter as 2019/20, as global LNG supply capability continues to exceed global demand,” it said. All of those sources add up to 509mn m³/day and storage can add another 103mn m³/d. The 1-in-20 peak demand day requirement is 531mn m³/d. – William Powell |