LNG market expansion needs South Asian demand [Gas in Transition]

LNG’s penetration into South Asian markets is significant, but nowhere near its potential. India, Pakistan and Bangladesh represent combined markets of some 1.7bn people. These countries are characterised by static or falling domestic gas production combined with high rates of energy demand growth and a desire to increase the use of gas within their economies to supplant costlier and/or higher emissions fuels.

However, South Asian markets are what is known in LNG analyst parlance as ‘price-sensitive.’ What this means in practice is that typically state-owned buyers have low levels of creditworthiness and entrenched debt, the product of being on the wrong side of energy and industrial subsidies. The sale price of electricity and other gas-based products, such as fertilisers, are often below the cost of production in the domestic market, creating a vicious circle of indebtedness.

Retreat from the spot market

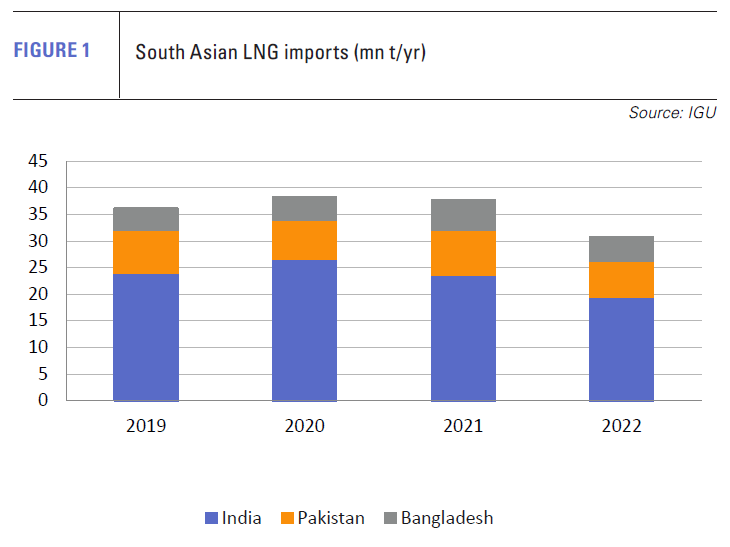

In 2022, as LNG prices rose to record levels, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh all retreated from the spot market, and relied on long-term contracts, which in the case of the latter two at least were insufficient in volume to meet demand for imported gas in full. Indian LNG imports dropped 15.4%, Pakistan’s by 20.6% and Bangladesh’s 17.9% as South Asia was outbid by wealthier countries (see figure 1).

In South Asia’s gas markets, high prices cannot be passed through to consumers and the cost burden falls on intermediaries, including state utilities and importers. As a result, if LNG prices are high, these countries reduce imports, even if this means gas and power shortages.

Their lack of creditworthiness also makes them unattractive options for sellers. In 2022, some of Pakistan’s tenders received no bids at all, amid a market thirsty for scarce cargoes.

However, as LNG prices moderate, South Asian LNG demand is returning. Moreover, South Asia’s growth prospects mean that the region should play a major role in the next few decades of LNG market development.

China is an economic powerhouse in comparison to India, but the demography of South Asia is much more promising. India’s population alone is now larger than China’s and its working age population is set to boom, while China’s contracts. Pakistan and Bangladesh have a similarly young and expanding workforce.

As more US and Qatari export volumes become available post-2025, South Asia will likely become home for a significant share, but the region’s economic and financial instability mean that it will still be a risky and price-sensitive market to enter.

Dollar crisis hits Bangladeshi LNG imports

Bangladesh had hoped to import 48 spot cargoes of LNG in 2023, but as a result of a dollar crisis, was able to import only 23. The country’s foreign currency reserves have more than halved since mid-2021, owing to a persistent trade deficit. State oil and gas company Petrobangla has been unable to import LNG cargoes because of the shortage of foreign currency.

In January last year, the government imposed steep gas price increases, but this resulted in large-scale non-payment by state-owned power and fertiliser plants, further reducing Petrobangla’s capacity to pay for LNG imports and monies owed to domestic gas producers. Towards the end of last year, the company was seeking a co-financed $500mn loan from the Islamic Trade Finance Corporation, part of the Islamic Development Bank Group to pay for LNG imports.

As a result, spot imports of LNG are unlikely to increase substantially this year – Petrobangla is targeting 24 cargoes, 13 in the first half of 2024. At the same time, Oman and Qatar gas, which have long-term supply agreements with Petrobangla, are reported to be providing only the minimum quantity allowable to fulfil the contracts.

Long-term demand strong

Despite this tentative return to the spot market, the longer-term outlook looks more positive. Bangladesh’s Summit Group announced in January that it had signed a preliminary agreement to supply Petrobangla with 1.5mn t/yr of LNG for 15 years. It was the latest in a series of long-term supply deals, which should increase LNG supply into the country and help alleviate its severe gas deficit. Summit’s supply agreement, if approved by the government, would start from October 2026.

In June last year, Oman’s state-owned OQ Trading agreed a sales and purchase agreement (SPA) with Petrobangla for between 0.25-1.5mn t/yr of LNG. According to reports, OQT will supply at least four cargoes in 2026, rising to 16 in 2027 and 2028, and 24 cargoes a year from 2029-2035.

OQT already has a contract to supply Petrobangla with 1.0mn t/yr under an SPA signed in May 2018, which runs from 2019 to 2029.

Also in June last year, Petrobangla agreed a new 15-year SPA with QatarEnergy for 1.8mn t/yr from 2026. The contract will be fulfilled by LNG produced from Qatar’s North Field expansion project. Qatar is the provider of Bangladesh’s only other existing SPA, which is from RasGas III Train 2 for 2.5mn t/yr, spanning 2018-2033.

Then, in November, Petrobangla signed its third SPA of the year, this time with US company Excelerate Energy. This will provide 0.85-1.0mn t/yr of LNG for 15 years starting in January 2026; 0.85mn tons will be supplied in 2026 and 2027 and 1mn t/yr from then until the contract expires in 2040.

Bangladesh’s LNG supply under long-term contract will rise from 3.5mn t/yr currently to 8.3mn t/yr in 2030, assuming the original deal with OQ Trading is not renewed. This would far exceed the 4.6mn tons imported in 2022 from both long-term and spot imports and the 5.6mn tons recorded in 2021.

Petrobangla clearly wants to lock in volumes on a long-term basis and reduce its spot market exposure. However, spot demand is still possible, if domestic gas production continues to fall.

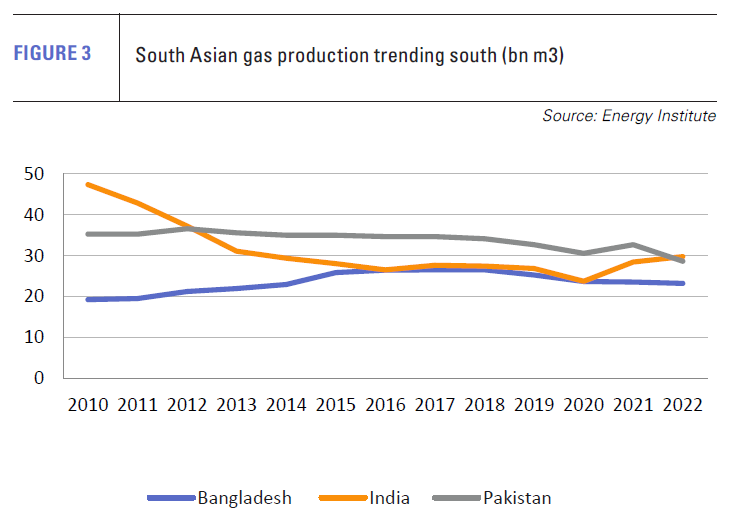

Domestic gas output stood at 23.3bn m3 in 2022, down from a peak of 26.6bn m3 in 2018. By the end of 2023, gas production had fallen to an annualised rate of 21.5bn m3, the lowest level since 2012. Gas producers are understandably reluctant to commit new funds to exploration and production while the government struggles to pay its existing bills.

Import expansion plans

The increase in long-term LNG supplies means more regasification capacity will be needed. Bangladesh currently has two floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) in operation at Moheshkhali, each with a regasification capacity of 3.8mn t/yr. Both FSRUs were provided by Excelerate Energy; Petrobangla owns the FSRU Excelerate Excellence, and Summit LNG (75%) the FSRU Summit LNG with partner Mitsubishi (25%).

There are various plans to expand import capacity. Construction of the $1bn onshore Matabari LNG terminal is expected to start in 2025, although a construction contract has yet to be awarded. The terminal has a planned capacity of 7.5mn t/yr.

Summit also hopes to secure an LNG Carrier for conversion to an FSRU, which the company says could be operational by second-quarter 2026. Excelerate Energy likewise is planning a second FSRU. Each of the proposed FSRUs would have a capacity of 3.75mn t/yr.

Pakistan seeks IMF stabilisation funds

Pakistan has faced no less of an economic whirlwind, with foreign currency reserves plummeting in 2022 and the government forced once again to go to the IMF for loans. Although Chinese lending under Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative has increased Pakistan’s foreign debt, energy sector mismanagement and an artificially high exchange rate are more fundamental problems.

Energy subsidies, designed to make domestic industry more competitive, have resulted in a large build-up of circular debt amongst banks and state energy companies, making it hard to pay for imported fuels.

The IMF’s announcement on January 11 that it would make about $700mn in loans immediately available to Pakistan provided welcome relief, but this is not the first time the country has had to depend on a bailout. There were signs of economic stabilisation in advance of the IMF decision, but breaking out of the current cycle of debt will almost certainly require unpopular reforms in a politically volatile environment.

The IMF’s announcement on January 11 that it would make about $700mn in loans immediately available to Pakistan provided welcome relief, but this is not the first time the country has had to depend on a bailout. There were signs of economic stabilisation in advance of the IMF decision, but breaking out of the current cycle of debt will almost certainly require unpopular reforms in a politically volatile environment.

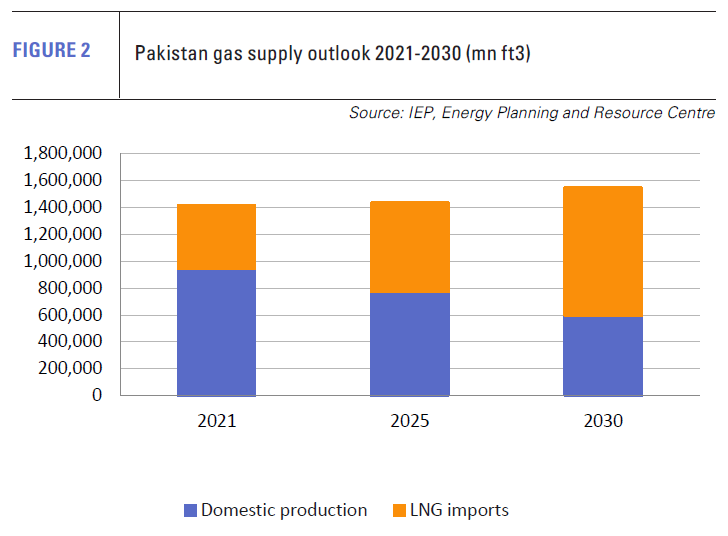

If a steadier economic course can be engineered, Pakistan has significant potential as an LNG market, but it will take time to recover from the recent period of high prices (see figure 2). Pakistan imported 6.91mn tons of LNG in 2022, down from 12.2mn tons the previous year. Having been largely spurned by the spot market in 2022, it did not make a single spot purchase until October 2023, for a cargo arriving in December.

It has relied on its long-term contracts instead, but even these failed to some extent. Trading house Gunvor cancelled four cargoes due in April, May and June of 2022, the last year of a contract for 0.78mn t/yr, running from July 2017 to July 2022. Italian major Eni also cancelled a cargo in 2022, having cancelled three in 2021. Its contract with Pakistan Energy Ltd is for 0.75mn t/yr from 2017-2035. Pakistan also has a long-term SPA with Qatar for 3.75mn t/yr from 2016-2031.

The cargo awarded in October to trading house Vitol for December delivery was thus the country’s first spot purchase in over a year, despite widespread gas and power shortages. Tenders issued in June did not return sufficiently affordable prices and were not taken up. Nonetheless, with two cargoes in December, Pakistan has returned to the spot market. The situation is far from stable, but at least the number of bids into the latest spot tenders has risen.

It is also likely that Pakistan, like Bangladesh, will seek to boost committed long-term contract volumes to reduce its spot market exposure. The problem is that an SPA with a buyer with low credit ratings carries less weight with the bank when a project developer looks for finance on the back of off-take agreements.

Demand outlook underpinned by falling domestic production

Pakistan needs gas badly and domestic production, which is priced lower than imported gas, continues to fall. In 2022, the country’s gas production fell 12.2% to 28.7bn m3(see figure 3). A lack of major discoveries over the last two decades has steadily reduced the country’s reserves, while demand has grown. A significant gas condensate discovery was announced in Sindh province in November with good initial flow rates, but has yet to be fully assessed.

Gas shortages for industry over the past year have caused a slowdown in industrial activity and exports, exacerbating the country’s weak foreign reserve position. Latent gas demand is higher than can be met by both domestic production and the country’s two FSRUs, even if they operated full time. These are the 4.8mn t/yr Excelerate Exquisite and the 5.0mnmt/yr BW Integrity, both located at Port Qasim.

Based on government forecasts to 2030 published in May 2022, demand for gas will rise strongly in the residential and commercial sector as will industry use, particularly for fertilisers. In contrast, demand for gas from the power sector is expected to fall. Domestic production will continue its seemingly irreversible decline, and, as a result, LNG demand will double from 13.5bn m3 in 2021 to 27.0bn m3 in 2030.

Whether this is borne out depends heavily on Pakistan’s ability to pay for imports. LNG demand will return, but only if prices continue to fall and the internal economic situation stabilises. As with Bangladesh, both countries' long-term LNG demand depends heavily on domestic reform.

Nonetheless, on the supply side of the equation, with large expansions in US and Qatari LNG capacity on the horizon, the market could well turn in buyers’ favour with more sellers willing to step into less creditworthy markets.