Germany (re)turns to gas [Gas Transitions]

In October the German government will be holding a conference in which it is expected to indicate how it sees the role of gas evolving in the coming decades. According to the German financial newspaper Handelsblatt, Berlin is likely bet to heavily on renewables-based hydrogen. At the same time, Berlin is not preparing to say goodbye to natural gas yet either.

In an article published on 31 July, Handelsblatt quotes from a draft policy paper from the ministry of economic affairs and energy, which states that “gaseous energy carriers will be integral and long-term components of the Energiewende [energy transition]…. Electricity based gases such as hydrogen will substitute for natural gas continuously, especially after 2030.”

A spokesperson from Zukunft Erdgas, the major German gas industry association promoting the use of gas in Germany, which has been involved in preparatory meetings with the government, confirms to NGW that the government is likely to take a positive view on the role of hydrogen and natural gas in the energy transition.

For the German government the switch to hydrogen represents a new direction. Although the German gas industry has been actively promoting “power-to-gas” for some years now, and quite a few projects have been started up, all-out support from the government has thus far been lacking. Policy-makers regard hydrogen rather sceptically, notes Handelsblatt. The government was aiming at an “all-electric society” and viewed the conversion of renewable electricity to hydrogen as inefficient.

"The continued use of the gas network is necessary for a successful Energiewende”

The thinking in Berlin seems to have changed, however. The policy paper notes that hydrogen based on renewable electricity (“green hydrogen”) could be a foundation for strong CO2 emission reductions in the steel and chemical industries. In the transport and buildings sector it could also make a “decisive contribution.”

The ministry acknowledges that the production of green hydrogen is accompanied by significant conversion losses, but it also has significant advantages: it can be stored easily and can be used in heavy transport where electricity-based alternatives are less feasible. In addition, it will allow for the continued use of the existing gas infrastructure. According to the draft policy paper, the continued use of the gas network “is necessary for a successful Energiewende”. It adds that “political decisions are needed to make the use of hydrogen in the existing infrastructure possible.”

One of the reasons the government is turning to hydrogen is that it has discovered that Germany's energy-intensive industry has few other alternatives if it wants to “decarbonise.” The paper notes that domestic production of green hydrogen is required “in the short to medium term on the grounds of industrial policy” and “in the long term as substitution for fossil-based gases.”

The new-found enthusiasm for hydrogen is not confined to the ministry of economic affairs, notes Handelsblatt. The environment ministry has also recently started up an “action programme for electricity-based fuels.” And in July, chancellor Angela Merkel emphasised the importance of hydrogen when she visited the Siemens facility in Görlitz. Siemens has announced plans to close its gas turbine plant in Görlitz, which is in a mining region in eastern Germany, and turn it into a hydrogen research laboratory and innovation campus.

“We observe that the federal government has clearly changed its thinking with regard to hydrogen and synthetic gases,” Timm Kehler, director of the industry association “Zukunft Erdgas”, told Handelsblatt. Kehler would like to see the government take measures to allow 20% hydrogen to be added to the gas grid. He says this would be “useful and technically feasible.”

Even the German Greens have become convinced of the usefulness of hydrogen, writes Handelsblatt. “Where direct use of electricity is not practical, hydrogen will become indispensable,” said Ingrid Nestle, energy spokeswoman of the Greens.

Coal-to-gas switching

All this is good news for those who are involved in hydrogen. But what about conventional natural gas? Germany has not written that off either.

According to the ministry’s draft policy paper, quoted by Handelsblatt, natural gas will continue to perform a bridge function for many years, although from 2030 on, its role will “gradually decrease.”

In fact, there are reasons to believe that Germany has only just entered the age of coal-to-gas switching. Most experts agree that countries relying heavily on coal power can make big, quick wins in reducing CO2 emissions by switching from coal to gas. The UK for example has easily outperformed Germany in reducing CO2 emissions – despite Germany’s costly Energiewende – mainly thanks to coal-to-gas switching.

According to figures reported by the website Carbon Brief earlier this year, the UK has reduced its CO2 emissions by 38% since peak year 1973, “faster than any major developed country.” The largest driver, notes Carbon Brief, “has been a cleaner electricity mix based on gas and renewables instead of coal”. (The second largest driver, by the way, was energy efficiency.) The main factor in promoting coal-to-gas switching, the report adds, has been the carbon price floor in the UK.

By contrast, German greenhouse gas emissions stagnated for a long time: in 2017 they were the same as in 2009 (see this briefing on the website Clean Energy Wire). The main reason was that Germany’s expansion of solar and wind power largely replaced nuclear power, which is being phased out in Germany, instead of coal power. Coal power was cheaper than gas-fired power, because the CO2 price in the EU Emission Trading System (ETS) was low and unlike the UK, Germany has no carbon price floor.

“Since January, we have seen the high carbon price really making the perfect market for gas”

Last year, however, this picture has started to change. Germany finally managed to achieve a significant reduction in its greenhouse gas emissions, of 4.2%. This year the country seems on course for another significant reduction. The reason: a steep drop in coal power production.

In the first six months of 2019, generation from brown coal (lignite) was down 21% and hard coal 24%. By contrast, gas generation grew 16% (by 3 TWh), wind power 19% (by 11 TWh) and solar 6% (by 1 TWh). (Sources: Karsten Capion, “Why German coal power is falling fast in 2019”, Carbon Brief, 18 July 2019, and Freja Eriksen, “Lower energy use puts Germany on course for further emissions reduction”, Clean Energy Wire, 30 July 2019.)

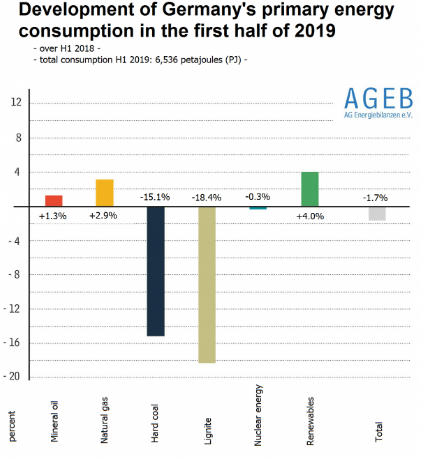

In terms of primary energy consumption, gas use grew 2.9% in the first half of 2019, whereas consumption of hard coal and lignite fell by 15.1% and 18.4% respectively:

Source: Lower energy use puts Germany on course for further emissions reduction, Clean Energy Wire, 30 July 2019

In the month of June 2019, emissions from Germany’s fossil fuel power plants were down by a third thanks to coal-to-gas switching, solar energy research institute Fraunhofer reported. Net power generation from lignite fell by 38% compared to June 2018, while power generation from hard coal fell by 41%. Gas-fired power plants, on the other hand, increased their production by 62%.

“The switch was caused by low gas prices combined with a rise in the cost of CO2 allowances in the EU Emission Trading System (ETS) and lower exchange electricity prices caused by a boom in renewables”, noted Clean Energy Wire (CLEW). Simply put, what happened was that “generating electricity from lignite became more expensive than the alternative, gas.”

“Since January, we have seen the high carbon price really making the perfect market for gas,” Yan Qin, lead carbon analyst at Refinitiv, a global data analyst owned partly by Blackstone Group, told CLEW. “We really see an interesting phenomenon: in the daily German power market, a high carbon price and very low gas price is really pushing gas in front of lignite.”

For the gas sector this is all quite exciting news, in particular since the German government is making serious moves, after phasing out nuclear power, to also start phasing out coal power. The government “is in negotiations with coal mining and power generation operators such as RWE about shutting down power plants in line with the recommendations of the coal exit commission,” explains CLEW. “The commission had proposed to end coal-fired power production in Germany by 2038 at the latest, and the government must now decide on the recommendation’s implementation.”

Interestingly, Refinitiv predicts that the first phase of the German coal phase-out will coincide with the last phase of the nuclear phase-out, in 2021-2022, which will make German power supply “a bit tight”. “This could also mean more work for existing gas plants,” writes CLEW.

Openings for gas

The bright prospects for gas in Germany and other European countries, were confirmed recently by Thomas Brehler, global head of power, renewables and water at KfW IPEX-bank, an arm of Germany’s state-owned development bank kfW. In an interview with Bloomberg news agency (“Giant Bank Sees Gas Plugging Gaps in Europe’s Energy Shift”, 10 July 2019), Brehler said that government plans to quit coal and nuclear power may create openings for gas in the region.

“In Europe, lots of investments are going to offshore wind, also for onshore, and not so much is going to gas,” Brehler said in an interview in the bank’s headquarters in Frankfurt. “There are more chances for gas-fired power plants expanding further, starting for Germany where we will see a lot of nuclear and coal power plants being shut down.”

Natural gas, the least polluting fossil fuel, offers the most practical backup for renewable generation until grid-scale storage arrives, said Brehler. KfW, it should be noted, is one of the world’s largest investors in clean energy, which makes Brehler’s assessment quite significant. KfW has provided $16 billion in loans to clean energy, trailing only the European Investment Bank in Europe, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance (NEF).

Bloomberg notes that Brehler’s remarks “highlight the potential for natural gas to remain a key energy source even as European politicians work toward slashing fossil-fuel emissions…. For KfW, [the] transition toward cleaner forms of energy will require gas plants as a way to make up for variable power supply from wind and solar farms.”

"There are more chances for gas-fired power plants expanding further, starting for Germany where we will see a lot of nuclear and coal power plants being shut down”

Gergely Molnar, a gas analyst at the IEA, told Bloomberg that it is “very probable that gas power plants usage will increase as Europe transitions to low-carbon energy generation.” This year, notes Bloomberg, “utilisation rates have already improved as natural gas prices in the region fell to their lowest in almost 10 years, making them more competitive against coal.”

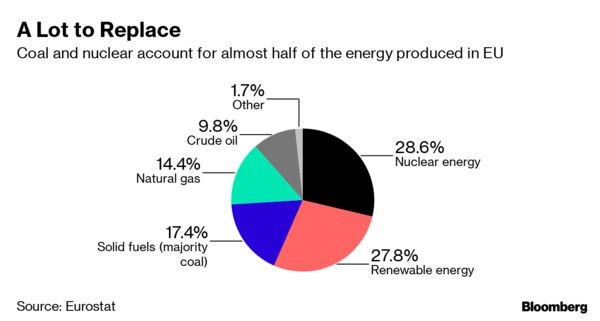

According to Bloomberg, about 40 gigawatts of coal and nuclear capacity will shut down in northwest European countries by 2025, enough to supply 80mn households, according to announcements by governments and companies.

Source: Bloomberg (note that the figures refer to electricity production, not “energy”)

Short-term opportunities

These upbeat forecasts are not reflected in the IEA’s Gas 2019 report, which came out in June, and which foresees gas demand for power generation grow by no more than 0.6%/yr in the coming five years in the EU. According to this report, gas demand will be constrained by the development of renewables. In 2018, gas demand in Europe decreased by 2% after three years of consecutive growth.

However, the IEA also published a report in July on “The Role of Gas in Today’s Energy Transitions”, which is quite positive about the contribution coal-to-gas switching could make to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, particularly in Europe and the US.

The IEA finds that “existing infrastructure in the power sector offers an immediate opportunity for major additional emissions reductions, if the economic and policy conditions are right. This would be enough to turn the rising emissions trend around and get global emissions back down to where they were six years ago.”

“We estimate that up to 1.2 gigatonnes of CO2 could be abated in the short term by switching from coal to existing gas-fired plants, if relative prices and regulation are supportive”, notes the IEA. “The vast majority of this potential lies in the US and in Europe.”

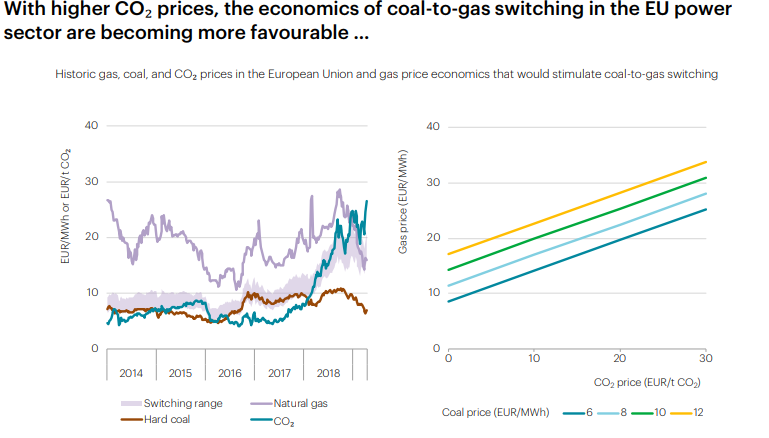

The report notes that the conditions for coal-to-gas switching in Europe have improved markedly in recent months, thanks to relatively low gas prices and an increase in the CO2 price in the EU ETS, a result of a reform of the ETS by the EU. “Since 2010, high natural gas prices and low CO2 prices have ruled out significant coal-to-gas switching in most EU countries”, but “with higher CO2 prices, the economics of coal-to-gas-switching in the EU power sector are becoming more favourable”, notes the IEA. This is illustrated in this chart:

Note: The “switching range” in the left-hand chart is the level below which gas prices need to lie to encourage coal-to-gas switching; the range indicates the price levels in which most of this switching would occur across the European Union’s power fleet. The lines on the right-hand chart show the level below which gas prices need to fall for a 55% efficiency gas plant to replace a 38% efficiency coal plant in the merit order (efficiencies represent weighted averages for the European fleet). Source: IEA analysis based on Bloomberg data.

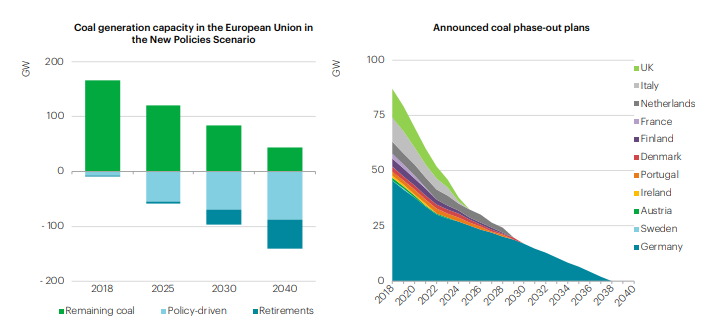

The IEA notes that coal generation capacity in the EU is scheduled to be reduced sharply over the next thirty years, providing “additional short-term opportunities for gas”, particularly in Germany, as shown in this chart:

Source: IEA

The IEA’s analysis makes a distinction between the prospects for existing and new gas plants.

Compared with building renewable capacity, “switching to existing gas plants can provide faster emissions reductions”, says the report. “This can be an important consideration for a European energy system focused on delivering a rapid turnaround in emissions.”

For example, “replacing a supercritical coal plant with an existing 400 MW combined cycle gas power plant could provide a slightly higher level of CO2 savings in the first five years of operation than a new onshore wind project (given the time needed to commission new renewable capacity).”

"The future for gas in Europe’s electricity market depends, in particular, on how services such as flexibility and capacity provision are remunerated"

However, the report adds that “the costs of renewables are falling rapidly, making several mature technologies, such as onshore wind and solar PV, very competitive with the costs of generating electricity from existing gas-fired power plants …. As in the US, the role of switching in Europe is therefore time-limited.”

With regard to new gas-fired capacity, the case is more challenging. “Weak wholesale power prices in renewables-rich systems are not incentivising investments in new thermal capacity; over half of the revenue from a new combined cycle gas turbine would, therefore, need to come from sources other than wholesale power prices”, writes the IEA. As a result, “gas plants may largely remain on standby and recover their costs by fulfilling balancing functions, rather than providing significant quantities of baseload power.”

Thus, in addition to simple coal-to-gas switching, the IEA also sees an important continued role for gas – and gas infrastructure – as a balancing and backup provider. It notes that “gas infrastructure is sized to meet significant peaks in Europe’s energy service demand”, and that for this reason “gas fulfils security and seasonal balancing functions that are not easily replicated by a renewables-based power system”.

Short-term peaks in the demand for gas are set to rise to help integrate growing shares of renewables, notes the IEA. “There is, therefore, a strong case for gas-based infrastructure for flexibility and back-up capabilities”.

The IEA does add that the role of gas as flexibility and back-up provider is challenged by “increasing investments in battery storage and grid management capabilities [e.g. demand response]”, but it regards the potential of these methods as “not yet definitive.” The report notes that demand-side response, for example, can reduce peak loads in Europe by up to 25% by 2040, while “cheaper battery storage could obviate the need for a further 5 GW of peaking gas plant capacity”, which is around 10% of total peak gas capacity.

The IEA’s findings thus give support to the idea that the German government is apparently coming round to: that gaseous fuels and gas infrastructure will be needed to make the Energiewende a success.

The question now is whether Germany will translate this vision into a convincing energy policy – and whether the EU will do the same in its upcoming “gas package”, expected in 2020. According to the IEA, “the future for gas in Europe’s electricity market depends, in particular, on how services such as flexibility and capacity provision are remunerated and incentivised.” That leaves the initiative with Berlin and Brussels.

How will the gas industry evolve in the low-carbon world of the future? Will natural gas be a bridge or a destination? Could it become the foundation of a global hydrogen economy, in combination with CCS? How big will “green” hydrogen and biogas become? What will be the role of LNG and bio-LNG in transport?

From his home country The Netherlands, a long-time gas exporting country that has recently embarked on an unprecedented transition away from gas, independent energy journalist, analyst and moderator Karel Beckman reports on the climate and technological challenges facing the gas industry.

As former editor-in-chief and founder of two international energy websites (Energy Post and European Energy Review) and former journalist at the premier Dutch financial newspaper Financieele Dagblad, Karel has earned a great reputation as being amongst the first to focus on energy transition trends and the connections between markets, policies and technologies. For Natural Gas World he will be reporting on the Dutch and wider International gas transition on a weekly basis.

Send your comments to karel.beckman@naturalgasworld.com