Germany plans for a net-zero carbon world [NGW Magazine]

Just before it took over the presidency of the EU, the German government approved June 10 the country’s National Energy and Climate Plan to 2030 (GNECP). At the same time, it also approved a new national hydrogen strategy (GNHS).

Together these schemes constitute a big step in shaping Germany’s shift away from hard and soft coal to pastures greener.

Germany has set out its wish-list: renewables, improved energy efficiency and renewable hydrogen will do the heavy lifting. The key targets the country plans to achieve by 2030 include bringing the share of renewables in the power mix from 40% to 65% and up to 27% in heating and cooling; up to 14% in transport; and cutting greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by at least 55%. On the negative side, efficiency measures are to see a 30% cut in fuel demand compared with 2008.

Germany is one of only about ten countries globally to enshrine in law the goal of net climate neutrality by 2050. Another is the UK, whose plan, as observers point out, omits to explain the engineering behind the neatly converging graphs. The technological advances and lower prices are givens.

The quest for carbon neutrality is bringing carbon capture and storage (CCS) back on the table, especially as a means to deal with unavoidable CO2 emissions, as for example in cement production.

The plan says: “The energy transition is a programme of modernisation and investment. It represents a huge economic opportunity for innovative companies – not only within the German and European markets, but around the world.”

But it recognises that “policies are needed to support and accompany this shift, resulting in a fundamental transformation in the way we live and do business.” For the first time, the plan includes legally-binding carbon budgets for each sector: transport, buildings, agriculture, industry, energy and waste management. The government also approved in May a CO2 price of €25/metric ton to be charged from January 2021 to the transport and heat sectors to hasten transition.

The structure of Germany’s climate targets is illustrated in Figure 2. These will be monitored annually by the energy ministry and an independent commission of energy experts.

_f650x548_1596444971.JPG)

GNECP does not contain details on coal as this is the subject of a separate national debate. In a major step, Germany’s Bundestag and Bundesrat approved a programme to phase out coal by 2038.

Implications on Germany’s energy mix

Provisional projections of the energy mix resulting from existing GNECP policies are shown in Table 1. According to this, primary energy consumption will have dropped by 20% by 2030. The share of renewables is expected to go up by 12% over the same period, with lignite consumption experiencing the biggest drop.

By 2039 over 30% of renewable energy will be provided by onshore and offshore wind, with photovoltaics providing about 12%.

The proportion of domestic energy sources is dropping as a result of the nuclear power phase-out and the reduction in lignite use, which means continued reliance on energy imports.

Gas use remains relatively constant in the baseline scenario, benefiting from the reduction of lignite in electricity generation. Because over 90% of natural gas is imported, total energy import dependency remains high, with imports accounting for around 65% by 2030 and almost 66% by 2040.

Hydrogen strategy

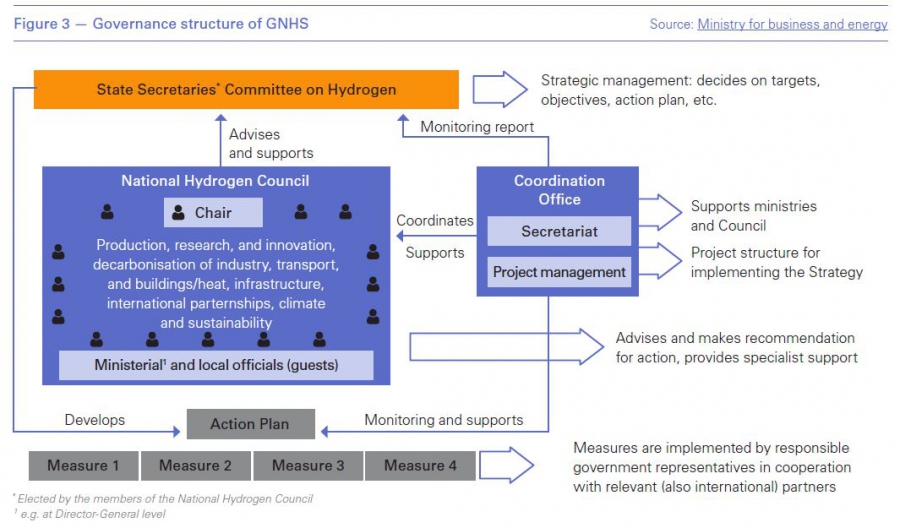

Germany’s national hydrogen strategy is a key element of the country’s planned carbon-neutrality date of 2050. This is considered to be crucial for the decarbonisation of industries that cannot be electrified, such as the steel and chemical industries and the transport sector and it has generally been well received. It will be led by a national hydrogen council, appointed specifically for this purpose (Figure 3).

The strategy considers only renewable, or green, hydrogen – produced through electrolysis using renewable electricity – as a sustainable solution in the long-term, aiming to take a global lead in its production and applications.

The German government will not exclude the use of grey and blue hydrogen during the transition. Given the targets for green hydrogen, set by the GNHS, and the needs of industry, this is likely to take over 20 years although it remains undefined.

German industry has promoted the acceptance of blue hydrogen by the EU, at least during energy transition.

In support of the GNHS, the government is providing €7bn to ramp up domestic production and €2bn to establish international partnerships for green hydrogen production and import.

The target is to achieve 5 GW of electrolysis capacity for green hydrogen production by 2030, and to double this to 10 GW by 2040, to provide a tenth of Germany’s total electricity capacity.

This would require access to considerable amounts of renewable energy, estimated to be 20 TWh by 2030, presumably to be generated by wind. It is not clear that the GNECP has allowed for this.

This is what led Germany’s minister for the environment, Svenja Schulze, to say during the presentation of the strategy: “Whoever says yes to renewable hydrogen must also say yes to wind energy.”

In order to develop a home-market for green hydrogen, the German government is considering mandatory blending quotas in aviation and the natural gas network.

GNHS includes an action plan with a number of measures the government intends to take during a first-phase ramp-up to 2023, including an improved regulatory framework. Then comes the next phase, when “the domestic market will be consolidated and European and international dimensions established.” Altogether the action plan identifies 38 steps that it considers necessary for GNHS to succeed.

Counting on its ability to turn green hydrogen into a successful export industry, Germany has made the creation of a European hydrogen infrastructure one of the priorities of its EU Council presidency that has just started.

Natural gas

The authors of the GNECP accept that gas will continue to represent a significant proportion of the energy supply in Germany, but also the EU as a whole, well into the future (Table 1). A major supply disruption could cause significant losses. The plan states that “resilience to supply crises should therefore be maintained and where necessary increased in order to reduce yet further the likelihood of such crises and increase preparedness for a deterioration in the supply situation.”

All gas supply undertakings operating in Germany must comply with clearly defined public service obligations, including: supplying gas to the general public which is as reliable, cost-effective and sustainable as possible; ensuring the stability of the network; and supplying gas at times of disruption, “provided that they can reasonably be expected to do so on economic grounds.” Regional co-operation, with other transmission system operators in neighbouring member states, is also to be considered.

The GNECP states that natural gas supply is secure and reliable, with the petroleum industry ensuring cross-border flows of gas with all neighbouring countries, and “direct gas supplies from Russia and Norway through pipelines which do not transit through other countries.” This implicitly includes Nord Stream 2: the country suffered, along with many others, from interruptions in flows through third countries in the past.

GNECP expects the share of natural gas in electricity generation to increase as the use of lignite/coal drops (Table 1). But there are worries that unless the market is redesigned, not enough capacity will be built in time.

Given also that production of green hydrogen will be limited, even if GHNS targets are fully achieved, even by 2040 natural gas is still expected to provide the bulk of the 26% gases that are used in Germany’s primary energy consumption. In fact GNHS admits that “the domestic generation of green hydrogen will not be sufficient to cover all new [hydrogen] demand.”

Concerns

Climate change has risen close to the top of the list of concerns of the German people. A survey published in January shows that this is the biggest issue, after immigration and asylum policy, and far ahead of education and social policy.

It has also become a priority for the government. It has earmarked about €30bn for climate-related spending, including hydrogen, as part of the €130bn stimulus announced in June to help the country recover from the coronavirus pandemic.

Despite its ambitious targets, studies commissioned by German ministries raise doubts that the GNECP will achieve Germany’s 2030 Paris Agreement nationally determined contributions (NDCs). For example, the target to reduce primary energy consumption by 20% by 2020, by the end of 2019 was only being met half-way, which will mean a lot of catching-up to do.

The government said that the national energy and climate policy is being “continuously developed further,” but regulatory hurdles still stand in the way of some wind and solar.

In addition, given the targets in both the GNHS and EU’s hydrogen strategy, the point at which green hydrogen completely replaces natural gas in Germany and Europe is still several decades away. Even within the European Commission (EC) there is a realisation that a “one-size-fits-all approach” for clean gases may be tricky. Natural gas and blue hydrogen will be in use for a long time to come, as is realistically envisioned in GNECP projections.

For Germany, though, €30bn spent on climate-related investments will create jobs and fund the research and development needed. The EU’s recently- approved recovery plan and Germany’s presidency of the EU Council could prove multipliers.

_f650x560_1596444936.JPG)

_f900x495_1596445006.JPG)