Fossil Fuel Subsidies Rise Again

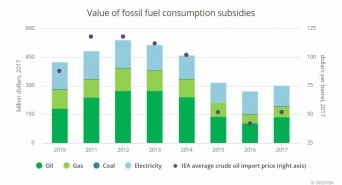

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has said that global oil, gas and fossil-fuelled electricity consumption subsidies almost halved between 2012 and 2016, down from the peak, reached in 2012, of over half a trillion dollars. However, the value rose again by 12% year-on-year in 2017 to around $300bn, owing to a 30% rise in oil prices, plus an 18% ($56.64bn) year-on-year rise in gas subsides.

Iran ranked first last year at $45bn, outpacing China. Iran's 2017 total includes $16bn in natural gas subsidies; Russia came second at $12bn. The report, published October 19 says that most of the increases relate to oil products, reflecting higher prices which, if there is no change in an artificially low end-user price, increases the estimated value of the subsidy.

Regarding rising oil prices this year (33% up on average in the first three quarters) it appears that subsidies are likely to increase again in 2018. The IEA said that 2018's rising oil prices are putting pricing reforms under pressure in some countries.

The top 10 countries with natural gas subsidies:

|

Country |

2016 |

2017 |

2017 consumption |

|

Iran |

13.876 |

16.348 |

214.4 |

|

Russia |

11.264 |

12.073 |

424.8 |

|

UAE |

5.533 |

5.947 |

72.2 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

3.54 |

4 |

111.4 |

|

Uzbekistan |

2.132 |

3.775 |

41.6 |

|

Turkmenistan |

1.758 |

2.1 |

28.4 |

|

Venezuela |

1.791 |

2.057 |

37.6 |

|

Algeria |

1.603 |

1.943 |

38.9 |

|

Oman |

1.248 |

1.552 |

23.3 |

Sources: IEA, BP. Bn $, Bn m3

The majority of those governments burdened by heavy subsidies also suffer from gas flaring. Cutting subsidiaries can, however, help them to invest in both enhancing efficiency and a reduction in gas flaring.

According to the World Bank-led Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership (GGFR), flaring declined to 140.6bn m3 in 2017, down by 4.7% from the 147.6bn m3 seen in 2016. However, Russia, Iraq, Iran, Algeria, Nigeria and other hydrocarbon-rich countries with huge subsidiaries remain at the top of this list of flarers.

The IEA said that many subsidies are poorly targeted and disproportionally benefit those wealthier segments of the population that use more subsidised fuel. It stated: “Such untargeted subsidy policies encourage wasteful consumption, pushing up emissions and straining government budgets. Phasing out fossil fuel consumption subsidies is a pillar of sound energy policy.”

The report states that high oil prices in the 2010-2014 period provided strong motivation for many oil-importing countries to pursue subsidy reform, adding that the subsequent fall in prices that began in 2014 presented an opportunity. A number of countries, including India, Indonesia, Mexico and Malaysia have, since then, implemented pricing reforms.

These reforms have also gained ground among fossil fuel exporters. In many cases subsidies represent a cost in the form of lost revenue, rather than an explicit financial burden, but the straitened circumstances of many oil and gas exporters in recent years have provided an impetus to make changes in their energy pricing; Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have all increased their domestic prices for gasoline, natural gas and electricity.

The IEA predicts that the rise in international fuel prices in 2018 could, however, set back efforts to phase out fossil fuel subsidies. Consumers in many oil-importing countries are facing a hike in retail prices, particularly in those developing economies that have currencies that are depreciating against the US dollar. The 75% rise in the dollar-denominated Brent crude price since January 2018 translates into a greater than 100% rise when realised in Indian rupees, and a 250% increase when priced in Argentinian pesos.

Given these pressures some countries have started pushing back their reform schedules by postponing price rises, or by otherwise protecting consumers from their efforts, while in most cases keeping the overall policy of market-based pricing in place. For example, despite higher international prices, Indonesia and Malaysia have kept domestic prices at previous levels, while India has cut the excise duty on gasoline and diesel, and Brazil has increased its subsidy on diesel.

These price controls can shield consumers from short-term changes in international market prices, but come with a fiscal and environmental cost. Moreover, they diminish the potential for higher prices to curb demand and bring the market back into balance.