Expanded BRICS: implications for global energy trading [Gas in Transition]

The BRICS group of top emerging economies, comprising China, Russia, India, Brazil and South Africa, took a leap forward at its summit in Johannesburg late August. Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been invited to join it in January 2024, fundamentally altering the world’s geopolitical, but also energy, landscape.

Once the invitations are accepted, the new group will have strong participation from all continents, except of course Australia, but also from the Middle East, giving its members an entry and a more prominent role in the emerging multipolar international system.

It is a major coalition of developing nations, providing them with a strong platform that they can use to better put their interests on the world’s agenda. Its stated objectives are:

- To enhance economic cooperation and trade among the member countries

- To promote sustainable development and inclusive growth

- To facilitate political cooperation and mutual understanding among member countries.

They have also agreed to “accommodate each other's core interests and major concerns, and respect each other's sovereignty, security, and development interests.”

It is worth noting that 23 countries had actually submitted applications to join the group. With six joining at this stage, there are potentially 17 more to go. BRICS is increasingly viewed by a growing number of countries in the ‘Global South’ as an attractive block of multilateralism.

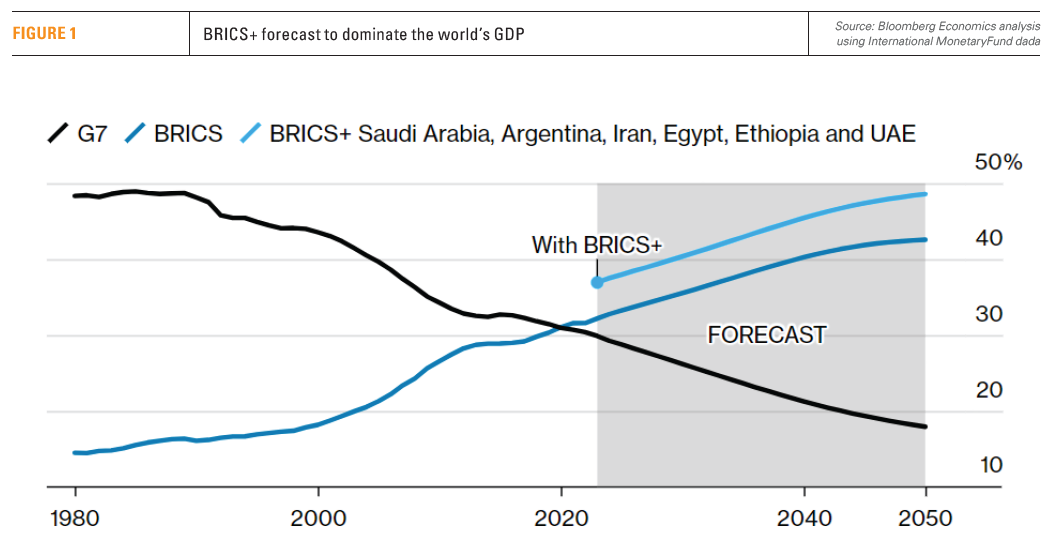

The expanded group, BRICS+, will account for over 37% of global GDP, ahead of G7’s 30%. In fact, it is forecast to dominate the world’s GDP, accounting for close to 50% by 2050, dwarfing the G7 (see figure 1).

This is likely to make BRICS+ more influential in the world economic sphere, especially as it is expected to advocate for a new global financial architecture and de-dollarisation of the global economy.

BRICS+ will be home to over 3.6bn people, about 45% of the world’s population, far ahead of the G7’s 800mn, making it a force to reckon with on the global stage.

The expanded group will account for over 38% of the total world industrial production and over 23% of exports.

BRICS+ will also control about 43% of global oil production, close to 45% of the world’s oil reserves and over 50% of natural gas reserves, and 72% of the world’s rare earth minerals. It will also account for 40% of the world’s energy consumption.

The expanded BRICS potential significance to world’s geopolitics, let alone the competition it could eventually provide to the G7, cannot be overstated. It provides a voice for a non-western world in search of its own identity. But it stresses that it is not an anti-west alliance. In what follows, the emphasis will be on the implications of BRICS+ on global energy trading, including natural gas.

Shift away from dollar dominance in global commodity trading?

Inevitably, the formation of BRICS+ is reinforcing calls for a shift away from dollar dominance in global commodity trading. Already about 80% of the trade between Russia and China is settled in either Russian rubles or Chinese renminbi. Russia is also trading with India in rupees. The UAE and India recently signed an agreement enabling them to settle trade payments in rupees instead of dollars. India used it to make the first oil payment in rupees this month. Russia and Iran are pushing for pricing oil in non-dollar currencies.

Clearly, BRICS+ members are already trading commodities with each other using their own currencies more extensively, rather than relying on the US dollar, and this will only but increase. The expansion of the group creates more opportunities for bilateral trading using local currencies.

Clearly, BRICS+ members are already trading commodities with each other using their own currencies more extensively, rather than relying on the US dollar, and this will only but increase. The expansion of the group creates more opportunities for bilateral trading using local currencies.

Egypt's supply minister said in April that the country is discussing with China, India and Russia using their currencies for commodity trading, but are yet to reach an agreement. Following the invitation to join BRICS, the country’s cabinet expressed the hope in a statement, that "the group's aim of reducing dollar transactions will lower the foreign currency pressure in Egypt." This would also be attractive to most other BRICS+ members.

Nevertheless, for oil, but also for other commodities, the reference price is predominantly, and by far, the US dollar. As a result, countries using alternative currencies to trade will still need to “use the dollar to determine the value of what they buy and sell.” It will take a long time to dent dollar dominance in global trading, but the BRICS are certainly chipping away at it.

Energy cooperation

Recognizing the potential for energy cooperation and complementarity among its members, in 2020 the group adopted a road map to build a strategic partnership in the energy sector by 2025. This is being done in three phases:

- Energy Research Cooperation Platform: to bring together experts, companies, and research institutes to coordinate their common interests in developing innovative technology and policies

- Identification of energy security needs and challenges to determine where cooperation can provide solutions

- Aims to advance mutually beneficial cooperation, including exchanging best practices, using advanced technology, and trade and investment opportunities in each other's economies

BRICS members are already well on the road of collaborating on energy solutions.

Implications on global energy trade

A common theme among most of the new BRICS members is energy. This could have been one of the selection considerations, as it strengthens the energy security, and security of commodity supplies, of the countries within BRICS+. There have been comments that the expanded group should be called ‘BRICS+OPEC’.

BRICS+ brings together some of the world’s biggest energy producers and consumers, be it oil, natural gas, coal or clean energy, as well as the minerals needed to support energy transition. This could have important implications for energy investment and trade. One shared interest these countries have is in creating mechanisms to trade in these commodities outside the reach of the G7 financial sector.

BRICS provides a platform to the Middle East but also to Africa. As such, it opens new trading avenues that can have major implications on energy investment and trading.

With China’s rising influence in the Gulf region, at a time when US interests are declining, BRICS membership strengthens the relationship of Gulf countries with one of their most important oil market partners.

Saudi Arabia’s presence, as the de-facto leader of OPEC+, in cooperation with the UAE, opens up new avenues in global energy trade. It adds a new dimension of influence in the global competition for access to oil and gas resources.

It also strengthens their hand to continue pursuing policies independent to US interests. For example, the Saudi-Russian oil partnership in OPEC+, their increasingly closer relationship with China, and Saudi Arabia’s refusals to toe the line on oil production at the behest of the US are indicative of what to expect.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) said in its September issue of its ‘Oil Market Report’ that “the Saudi-Russian alliance is proving a formidable challenge for oil markets.” This was prompted by their decision in early September to extend their combined output cuts of 1.3mn bls/d to the end of the year that triggered a price spike in Brent crude above $92/bl.

It will be interesting to see how the expanded BRICS fits into the realignment of global oil and gas trading, emerging as a result of the Ukraine war. As Daniel Yergin, vice-chairman S&P Global, pointed out, increased oil trading among BRICS members “will only serve to further divide what had previously been a single global market for the world’s most-traded commodity.”

With abundant natural resources under its belt, BRICS+ will play a major role in the global energy supply and security. It will have even greater influence on global oil and gas markets and trading than BRICS did before.

A coordinated approach among BRICS+ members on energy and commodity trade and flows could impact global energy security.

Energy investment implications

BRICS recognise the role of oil and gas “in supporting energy security and energy transition and see incentivizing energy investment as a way to address energy security challenges.” In order to facilitate this, they are working toward developing alternative financial mechanisms, including the establishment of the New Development Bank (NDB) in 2014.

BRICS+ membership could also be a catalyst to fresh investments in upstream oil and gas, particularly for Egypt that hopes to attract such investments from Chinese and Indian oil and gas companies, in addition to the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

BRICS+ membership could also be a catalyst to fresh investments in upstream oil and gas, particularly for Egypt that hopes to attract such investments from Chinese and Indian oil and gas companies, in addition to the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

Egypt’s President al-Sisi welcomed this when he said, “I appreciate Egypt being invited to join BRICS and look forward to coordinating with the group to achieve its goals in supporting economic cooperation.” This may take time, but for Egypt it is a much-welcomed lifeline.

Even before being invited to join, Saudi Arabia made it clear that it is keen to collaborate with China in developing natural gas, crude-to-chemicals and mining projects. Its energy minister, Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, said in June that Saudi Arabia is keen to pursue investments with China within and outside the country. Saudi Arabia is China's top oil supplier, delivering more than 2mn bls/d. Aramco is already investing in China in refineries and petrochemicals to ensure its long-term oil supply to the country.

The expanded BRICS is likely to see increasing energy investments in member countries subject to outside restrictions and sanctions, notably Iran. Its members have a shared interest in creating mechanisms to invest and trade energy and commodities outside the reach of the US and the G7.

For example, its largest members, China and India, have refused to join the ‘price cap coalition’ targeting Russia. The Saudi energy minister went as far as to say that the “kingdom will not sell oil to any country that imposes a price cap.” Such positions undercut the effectiveness of sanctions.

Climate change collaboration

BRICS established the NDB as a multilateral development institution to mobilise resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects. So far, the NDB has sanctioned almost $8bn in renewable energy and infrastructure projects across the BRICS countries.

NDB has a target to achieve 40% of its total volume of approvals to projects contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

South Africa has been the largest beneficiary so far, with 12 projects financed by NDB totaling $5.4bn, out of 123 approved projects between 2016 and 2022 totaling over $30bn.

BRICS have put in place, and are currently implementing, a ‘2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ with emphasis on poverty, hunger, health care, education, climate change, access to clean water, and environmental protection.

Although only 16% of BRICS countries' energy consumption is renewable, this is growing annually in response to commitments to mitigate climate change.

In May 2022 the BRICS countries held an on-line high-level meeting on climate change and considered strategies for expediting the shift towards low-carbon, accelerating climate resilient transition, and strengthening solidarity and cooperation on climate change. But they also pointed out that “developing countries face more difficulties and challenges in achieving the goals of global carbon neutrality in the context of the world economic recovery, achieving sustainable development goals, including making efforts to eradicate poverty.”

South Africa is pioneering clean coal technology, an area in which India and China are interested.

Saudi Arabia also wants to collaborate with China in developing its renewables projects, including importing Chinese expertise to localise production for the sector.

Challenges

One of the greatest challenges BRICS+ faces is that the existing and new member countries have geopolitical problems outside the group and are in constant competition, especially its biggest two members China and India.

Their interests are also very diverse, even if they have shared objectives. The economic, political, and social interests of BRICS+ members are so divergent that can hinder cohesive decision-making. In addition, some member states are facing serious security and political stability challenges.

On the other hand, with BRICS aiming to be a voice for the developing world, this diversity may be inevitable.

A downside may also be that the current Chinese and Russian influence may be seen inside and outside BRICS as leading to a greater anti-western tilt than ever before. However, it is unlikely that India, Brazil and some of the new invitees would let this get out of hand. Brazil’s President, Lula da Silva, made this clear when he said “it is not the intention of BRICS to oppose the G-7, G-20, or the US.”

But, as Lord Jim O’Neill, the coiner of the acronym BRICS, said after the Johannesburg meeting, “the influence of BRICS will depend on its effectiveness, not on its composition or size,” adding that “the group could be more effective…if key members were truly serious about pursuing shared goals.” That will be the key test for BRICS+.