The European Union, Ukraine and Russian Gas

The European Union imports significant quantities of oil and gas from Russia. The EU also imports oil and gas from the Central Asian republics, in particular Kazakhstan (oil) and Turkmenistan (gas), which also come via Russia.

Russia supplies 27% of the EU’s gas (125 Gm3 in 2013) and 32% of its oil (4.2 million barrels/day). No other source in the world can replace it in the short term. Russia exports 56% of its oil and 84% of its gas to the EU. No other market in the world can replace such a loyal customer in the near future, despite recent efforts by Russia to diversify into Asia. Not to mention other commercial trade, inward and outward investment and financial commitments.

Russia is the world’s largest exporter of hydrocarbons, both oil and gas, with 7.5 million barrels/day and 230 Gm3/year respectively. Gas exports generate income for the country of some €54.6 billion a year whilst oil exports generate four times as much, at €218.5 billion a year. Officially, 50% of Russia’s budget depends on the revenue generated by oil and gas; unofficially, the figure is much higher.

Russia oil exports are partially transported through the Druzhba – “Friendship” – pipeline, which ends in Leuna, in the former East Germany. The remainder of its exports to Europe is transported by tankers that are loaded with crude in either Primorsk, close to St Petersburg, or Novorossiysk, on the Black Sea in Ukraine. These cargos of Russian oils could easily be sent to other consumers and Europe, for its part, could find other sources of supply: oil is liquid and therefore fungible and transporting it only accounts for a few per cent of its price.

Gas remains problematic, however, since the pipes that transport Russian gas from Siberia to Europe obviously cannot transport it in other directions. Moreover, Russia cannot export its gas by other methods, given that it has not yet developed LNG, despite the numerous projects underway.

Ukraine and Russia

In the 8th century, Varangian trade (with the Eastern Vikings) from the Baltic to the Black Sea united the Slavonic tribes, and in the 9th century, Kiev was captured from the Khazars by the Varangian Oleg the Seer, founder of a “land of rowers" or Rodslagen, in proto-Slavonic Rus’: this was the golden age of its capital, Kiev. The territory of Rus’ covered the north of present- day Ukraine and Belarus and Western Russia. The name “Russians” comes from Rus’ as do the terms “Ruthenes” or “Rusyns”, used to describe the people of western Ukraine. The name “Ukraine”, which means “border march” in Russian, came with the expansion of Moscow, much later on. In the 11th century, the Rus’ of Kiev was geographically the largest state in Europe.

The ups and downs of history were to subject the people who now make up Ukraine to various neighbouring powers. It was not until 1917 that the Republic of Ukraine was formed, then conquered by the Bolsheviks in 1920 and incorporated into the USSR in 1922. In 1945, Russia brought Ukraine and Belarus into the UN with it. Ukraine would become independent in 1991 with the fall of the Soviet Union, whilst remaining a member of the Commonwealth of Independent States that was created as a “substitute” for the Soviet Union.

Until 2004, the Ukrainian regime was to remain very close to Moscow, allowing Ukraine to take advantage of a very low price for the gas it imported from Russia, at around 20% of the international price and the same as was billed to Russian consumers.

Disputes between Ukraine and Russia over natural gas

Russian exports of natural gas to Europe were to begin in the 1980s and clearly needed the gas pipelines that mainly passed through Ukraine. Until 1991, Russian (or Turkmen) gas was transported directly from areas that were closely linked to Russia (first Ukraine and later Czechoslovakia) to the European Union. Until a few years ago, 80% of Russian gas passed through Ukraine, with the remainder going through Belarus and Poland. Ukraine is itself a major gas consumer, both for energy production and for use as a raw material, in particular for producing nitrogen fertilizers. Intensive energy use and gas consumption have long been supported – as in all Soviet Union countries – by a very low price and management based on “central planning” by the famous GOSPLAN committee.

Moreover, the 1990s were marked by gas disputes between Russia and Ukraine, interruptions to gas supplies and the signature, in 1994, of an agreement that has never been implemented, on majority control of Ukrainian gas pipelines by Gazprom in exchange for a waiver of gas debts.

The 2006 crisis

Until 31 December 2005, Ukraine benefited from advantageous prices as a result of its strong relationship with Moscow and its status as a former member of the Soviet Union. The Orange Revolution and the election of Viktor Yushchenko, however, marked a break with the past and signalled Ukraine’s desire to build closer ties with the West.Gazprom then decided to align the price of Ukrainian gas with European prices, although it had previously been significantly lower ($ 50/1,000 m3, compared with $230 on the European market).

Moreover, Gazprom accused Ukraine of taking quantities of gas that were in excess of its needs and reselling the surplus to Europe, pocketing the difference in price. Following the failure of negotiations on the issue, Gazprom imposed an ultimatum, threatening to cut off Ukraine’s gas supply and only allowing European supplies through. Gazprom stopped deliveries on 1 January 2006, affecting a majority of European countries.

On 4 January 2006, the two sides agreed on a new price and transport tariff for gas. Gazprom began to re-supply the gas pipelines to full capacity. The billing price, however, was still only $95/1,000 m3 (compared with $230 for European countries), as deliveries were partly made up of gas from Turkmenistan at $50/1,000 m3. This price, however, was only fixed for the first six months, which was to lead to future disputes over increases. The transport price for gas increased from $1.09 per 1,000 m3 to $1.60 per 1,000 m3.

The 2008 and 2009 crises

On 2 October 2007, Gazprom threatened to suspend the supply of natural gas to Ukraine because of an unpaid debt of $1.3 billion. Following further threats to reduce deliveries of gas in 2008, presidents Vladimir Putin and Viktor Yushchenkoannounced an agreement on 12 February 2008: Ukraine would begin to pay its debts for natural gas consumed in November and December 2007 and the price of $ 179.50/1,000 m3 would be maintained throughout 2008..

The most severe difficulties would arise in 2009. On 2 January, following a dispute between Ukraine and Gazprom over the price to be paid in 2009 and a failure to pay for some deliveries in 2008, Gazprom reduced and then stopped deliveries of natural gas to Ukraine. Russia accused Ukraine of stealing gas intended for Europe to make up for the supply shortages it was facing and tried to increase the amounts flowing through gas pipelines passing through Belarus and Turkey. Most European countries, however, suffered very significant reductions in their deliveries of Russian gas and managers of the gas network implemented emergency plans. Some countries received no deliveries at all.

Gas deliveries restarted following a meeting on 20 January in Moscow between Vladimir Putin, then Prime Minister of Russia, and Yulia Tymochenko, Prime Minister of Ukraine. Russian exports had been stopped for three weeks.

Under the terms of the agreement signed with Russia, Ukraine was obliged to pay a price close to the international level.

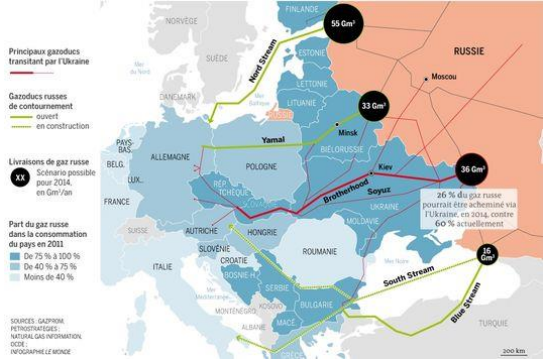

Attempts to circumvent Ukraine and end reliance on Russia

Conscious of the risks to European supplies of Russian gas created by going through Ukraine on several occasions since 1991, the major European gas companies and Gazprom suggested that the country should separate gas pipelines used for transit from those supplying the local market, both physically and legally, but met with a refusal from Kiev. Finally, four European groups (BASF and E.ON in Germany, Gasunie in the Netherlands and GDF Suez in France) joined forces with Gazprom to create two supply lines (two others are scheduled) in 2011 and 2012 from the Nord Stream gas pipeline, which can transport up to 55 Gm3/year of Russian gas.

This 1,224 km pipeline links Russia directly to northern Germany through the Baltic, without going via a third party, causing major concerns in traditional transit countries that were severely affected by the German-Soviet alliance during the Second World War. This ability to circumvent Ukraine comes in addition to the 33 Gm3/year of Russian gas destined for Europe, which passes through Belarus and Poland. A further 16 Gm3/year comes through the Blue Stream gas pipeline. This was laid in the Black Sea in 2002 to supply Turkey, in preference to enlarging the existing terrestrial gas pipeline running through Ukraine.

Whilst 80% of gas imported from Russia and Europe passed through Ukraine a few years ago, this can now be reduced to less than 30%. It could be reduced further still – to practically zero – if the South Stream project were completed. Nonetheless, the significant storage capacity in western Ukraine, which is used to secure supplies for Europe, raises numerous unknowns in relation to actually replacing it by using alternative gas pipelines. The South Stream gas pipeline, built jointly by Gazprom – BASF – ENI – EDF, would transport gas from southern Russia to Bulgaria, taking it under the Black Sea. Two branches would then take the gas to either Austria or Italy (although this second branch could be abandoned as a result of developing the TAP TANAP project – see below). The aim is the same as with Blue Stream and Nord Stream: avoid Ukraine. This 2,380 km gas pipeline (which runs under the Black Sea for 930 km) should see the first two of its four supply lines enter service in 2016 (31.5 Gm3/year). If it achieves its full capacity of 63 Gm3/year (in around 2019), gas may no longer pass through Ukraine. But the current situation – in early May 2014 – is forcing the European Union to oppose further work on the project, which has already begun. It should be noted that the Bulgarian authorities continue to support the project.

Source www.trans-adriatic-pipeline.com

Note that the latest version of South Stream no longer includes a branch to Italy, which would be well supplied with Azeri gas by TANAP and TAP. Eastern European countries, which are highly dependent on Russian supplies, are developing and building LNG terminals, particularly in Croatia, Lithuania and Poland.

The overthrow of the regime in 2014

Ukraine has been split by pro-Western and pro-Russian movements for many years. Viktor Yanukovych took the majority of votes in the east of the country and a minority in the west in the 2010 presidential elections.

Demonstrators occupied Independence Square in Kiev for over a month, starting on 1 December 2013. Amongst other things, they were critical of the authorities for having refused to sign the association agreement with the European Union, and the absence of the rule of law. In December, the European Union put pressure on Ukraine to sign the association agreement and suspended negotiations. Viktor Yanukovych then travelled to Moscow and secured a loan of $15 billion and a reduction of one third in the price of gas delivered by Russia. Russian gas is still just as important for Ukraine.

In January, the demonstrations in Kiev hardened and spread to other cities. The opposition is spearheaded by militants from the Svoboda nationalist movement and the more radical Right Sector and Common Cause. The movement resulted in the departure of President Yanukovych and his replacement by a provisional government. This caused unease amongst Russian- speaking people and prompted Russian intervention, with men and military equipment dispatched to Ukraine; this in turn prompted a vote on Crimean independence on 16 March, with the result, worthy of a Soviet ballot, showing a very clear majority in favour of Crimea becoming part of Russia.

Ukraine, gas and western aid

Ukraine is a major gas consumer. Admittedly, consumption reduced by more than 100 Gm3 during the 1990s to around 50, 20 of which are produced locally. However, Ukraine’s situation means it is unable to pay all its bills and it had accumulated debts to the value of $4.5 billion by June 2014.

By December 2013, Russia had agreed to offer Ukraine a loan of €10.9 billion and a 30% rebate on the price of gas, bringing it down to €195.5/1,000 m3 instead of €295.6/1,000 m3. The rebate was due to apply for five years, i.e. a saving of around €2.5 billion per year for Ukraine. The total package was worth €21.8 billion over five years. In return, Moscow hoped Ukraine would join its customs union, rejecting the association agreement with the EU.

The revolution in Independence Square wreaked havoc on the plan. Gazprom therefore informed its Ukrainian customer, Naftogaz, that the price of gas would increase on 1 April 2014 to €268.3/1,000 m3, an increase in cost of €2.18 billion over one year! The new price was equivalent to that found on European markets and went back on a reduction granted to Ukraine in 2010, following an agreement on leasing the military base in Sebastopol as a result of Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Moscow is making Ukraine and its western supporters pay the price. In light of the lack of an agreement on debt repayment, Gazprom suspended deliveries to Ukraine in June. The situation is not yet drastic since Ukraine’s storage facilities were over 50% full. Exports to Europe have not been affected.

But who will be willing to fund Ukraine in Russia’s place? The IMF? The EU? The EU has promised the new government a loan of €10.9 billion, the IMF €10.9 billion and the United States $1 billion, but in the long term, none of them will be prepared to pay a bill of around €8.7 billion a year for gas and €5.8 billion a year for oil on Kiev’s behalf. It will also be difficult to reduce imports, insofar as there are potential gas reserves in Crimea, where major companies such as ExxonMobil, Shell and Eni were preparing to drill.

Can Europe replace Russian gas?

Europe currently consumes around 500 Gm3 of gas per year; it produces just under half of this (and will probably produce less than a quarter in a few years), imports a quarter (around 125 Gm3) from Russia and another quarter from Norway, Algeria, Nigeria and Qatar. Can Europe do without Russian gas?

Reducing gas consumption in Europe

A lot of gas is used for heating premises; building insulation policies, which are in many cases already being implemented, should help to reduce demand, although in France, changes in thermal regulations are resulting in an increase in gas-powered heating in new buildings and a decrease in electricity. A significant proportion of the reduction, however, could come from replacing gas-fired power stations with coal-fired ones. This is what is currently taking place in Germany, where renewable energy sources now account for an increasing share of electricity production and their production capacity is approaching that of thermal sources. Irregularity of supply remains an issue, however, and thermal power stations are still essential. Gas-fired power stations, however, which emit low levels of CO2 are – paradoxically – being replaced by coal-fired ones, which are much more harmful in terms of greenhouse-gas emissions. Europe can import mass quantities of US coal, which is itself being replaced by shale gas to produce electricity in the United States. US coal is a low-cost replacement for natural gas, which largely has to be imported and therefore remains relatively high in price. And the cost of transporting natural gas is high.

Finding new sources of gas

Europe could import gas from new or different sources, but the solutions are complex.

Current suppliers would only be willing or able to increase their exports marginally. Norway would be unwilling so as not to position itself as a competitor to Gazprom. The same argument applies to Algeria, which appears to have limited reserves pending the possible development of shale gas. Qatar’s preference will be to develop Asian markets, which are currently more profitable.

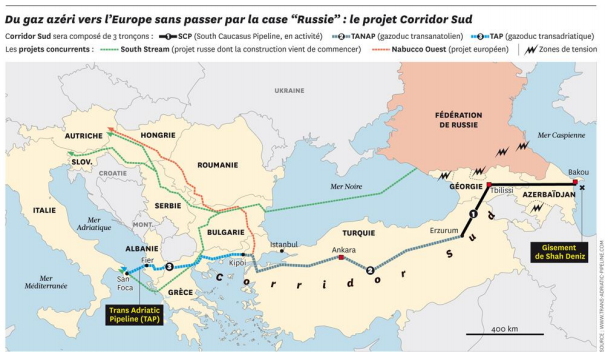

New suppliers could be approached: although the Nabucco project, which was supposed to supply central Europe with gas from Azerbaijan, has been abandoned, its rival TANAP - TAP, which finally emerged as the preferred option, will transport the same gas, but in limited quantities (around 10 Gm3, or 2% of European requirements). Significant resources exist in Iran and Iraq but their respective political and security conditions limit any prospects for short-term projects. Turkmenistan has very significant resources and already exports natural gas to Europe via Russia. An increase in exports to Europe, avoiding Russia, could only be achieved by going via the Caspian Sea or Iran, again raising considerable political difficulties.

The other option is more remote resources, with US shale gas in the forefront. US resources are considerable and American production will very quickly exceed requirements. Export plans have already been approved and initial cargos of LNG should leave Sabine Pass around 2016. Although, however, the number of projects announced is considerable – as it often is in such cases – there is no guarantee that many of them will come to fruition, if only because too high a level of exports would increase the price of gas in the United States. This very low price ($4 MBtu compared with under $10 in Europe and $16 in Asia) gives industry and the economy in the US a decisive economic advantage. Moreover, an increase in prices would destroy the possibility of arbitrage (with the price differential between the United States and Europe covering the costs of liquefaction and transport).

Other significant sources of gas exist, for example in East Africa (Mozambique and Tanzania) and Australia, but such sources are remote, expensive and better suited to supplying the Asian market.

In Europe and on other continents, biogas and shale gas are both sources that could emerge in the medium term. Many key players are working actively on biogas, with a view to mass production by 2030. With regard to shale gas, the concerns expressed by French public opinion do not seem to be unanimously shared in the rest of Europe.

Can Russian gas find other outlets?

Most Russian exports go to the European Union. The networks of gas pipelines that link the two regions form a very strong – and very expensive – connection. Not using them would represent a significant loss, particularly for Russia.

Russia may turn to Asia to export its gas: Sakhaline is already supplying Japan. Demand for gas in China and neighbouring countries is increasing rapidly, whilst production is stagnating. China already imports gas from Turkmenistan and the quantities imported from the Central Asian republics are set to increase rapidly. China has recently decided to cap its coal consumption because of unacceptable pollution levels in its cities. It will therefore need to replace coal with gas, which is much less polluting; gas consumption could double as a result in the next few years.

Discussions on gas imports between Russia and China have been underway for many years but hit a snag over the price for gas offered by the Chinese, which the Russians viewed as inadequate. The crisis in Ukraine has prompted Russia to accept a contract for $400 billion, which will cover the construction of gas pipelines between the Kovykta and Chayanda reserves in eastern Siberia and China, and the supply of 35 billion cubic metres of gas for 30 years. The estimated price for the gas is around $330/m3, which is close to the price paid in Europe. Other contracts between Russia and China, supplying pipelines from western Siberia, are possible.

Conclusion

The crisis in Ukraine has highlighted the interdependence between the European Union, Ukraine and Russia, as well as the EU’s weakness when faced with a supplier that uses energy as a political weapon. Creating gas pipelines to circumvent Ukraine (Nord Stream and Blue Stream, which have already been built, and South Stream, which is under construction – provided the European Union does not oppose it for ideological reasons) should provide a temporary guarantee of stability for Russian supplies, which have been remarkably reliable apart from the crises of 2006 and 2009, largely due to the negotiations on the price of gas between a supplier, Russia, and its only customer, Ukraine. The failure by Russia to ratify the European energy charter raises threats to transparency and the outcome of future reviews of gas prices between Gazprom and European energy companies.

The crisis may be a salutary shock treatment for the EU in its policy of diversifying sources of supply and promoting decentralized energy sources, in particular biogas and shale gas. For Russia, it will also have been an opportunity to develop a collaborative relationship with China, which will offer it the much sought-after diversification of its outlets; such a development will not, however, free it from the constraint of the significant investments required in transport and storage infrastructure, their funding requirements and the timescales involved.

This working paper by Jean-Pierre Favennec was originally published by the Research Centre for Energy Management (RCEM) at ESCP Europe Business School. RCEM is a Natural Gas Europe Knowledge Partner.

![]()

Jean-Pierre Favennec

In collaboration with JC Augey and Ph Vesseron July 2014

Sources:

Pierre Terzian – Article published in Le Monde dated 1 April 2014 Ria Novosti

Energy Charter

Naftogaz

Gazprom

Wikipedia – re.gas disputes