Energy production in a divided world [NGW Magazine]

Until 2019 there was a concerted global effort to reduce carbon emissions led by Europe, with strong support from China. But Covid-19 and the growing ‘cold war’ between the US and China have upended this.

While European energy markets have addressed climate change head-on, this is less the case in the US while China and India are giving priority to boosting coal and renewable energy.

With growing populations and aspirations to improve living standards, especially post-Covid-19, the two Asian countries are prioritising their domestic energy resources.

The developing situation is also impacting International oil companies (IOCs) and National oil companies (NOCs), but in different ways.

BP leads change

Ever since Bernard Looney took over as BP CEO, the company has been redefining its future strategy, announcing initiative after initiative, the final plan to be revealed mid-September.

BP will install methane measurement at all its major oil and gas processing sites by 2023, reduce methane intensity of operations by 50%, and increase the proportion of investment into non-oil and gas businesses over time.

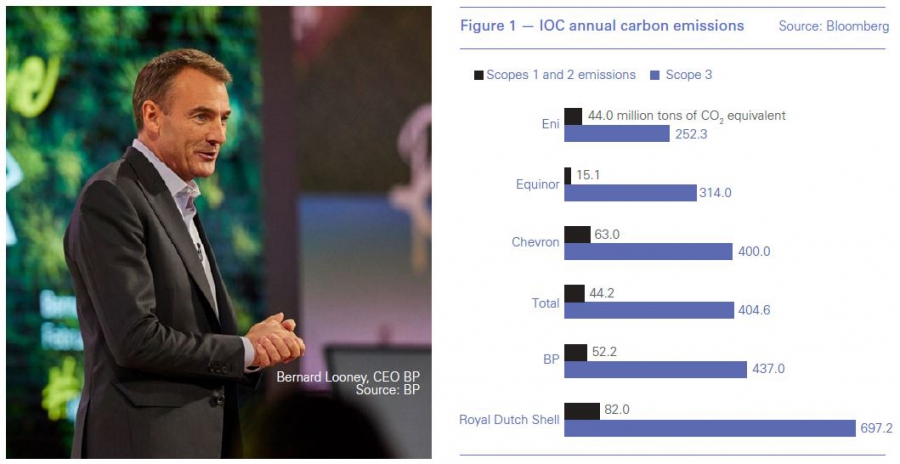

What is important about these initiatives is that BP pledges to take responsibility for the removal of Scope 3 emissions, which are indirect emissions in a company’s value chain including from use of products sold.

However he said BP will remain an oil and gas business “for a very long time.”

BP invests around $500mn/yr on renewable energy, including solar and biofuels – just over 3% of its $15bn annual organic capital investment budget. It was instructive that nearly all the adverse criticism came from media in Europe and the west, with very little excitement shown in Asia and Africa.

BP has already started shedding some of its carbon-intensive business, with the June 29 sale of its global petrochemical business to Ineos. “We have other opportunities that are more aligned with our future direction,” Looney said. That might also include dividend payments: BP remains committed to this for now, but will review it quarter-by-quarter. In 2019 this amounted to $8.5bn. But can this be maintained as it transitions to renewables? Conversely, if it does, will it be able to fund the transition? And if cannot, will BP still be attractive to its shareholders? Another tricky question is: will all other major IOCs follow BP’s lead and decarbonise by 2050?

European majors

Changing social attitudes to climate change have become an existential challenge for European majors. Balancing the need to find a way to mitigate the impact of climate change with an ever-growing demand for energy is critical to their future success.

By far the largest emitter among the majors is the Anglo-Dutch major Shell, in Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions (Figure 1).

However, none of these companies has specified how they will achieve their targets or details of their timetables to get there, except perhaps Eni. But in all cases it is likely to involve producing more gas and less oil, while migrating to renewables and investing in hydrogen.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the average investment by oil and gas companies in non-core areas has so far been limited to about 1% of total capital spending annually. There is a long way to go to achieve their new targets.

If successful, in the longer term European majors may become the role models for all other IOCs and NOCs to follow.

But in the meanwhile, with oil and gas expected to be needed well into the future – irrespective of what happens in Europe – the balance of oil and gas supplies needed to meet demand may end-up shifting to the NOCs of Asia and Russia, who would be more than happy to step in. They already own about two-thirds of global oil reserves.

As Nick Butler, chair Policy Institute at King’s College London, points out, “The volumes produced and sold by the European majors are of minimal importance in relation to the overall issue. The attention given to what these majors do or do not do has been wholly disproportionate. In total, the six companies produce just below 7mn b/d of oil – only 7% of global demand.”

Across the Atlantic, ExxonMobil has pledged to reduce methane emissions and has expressed support to the aims of the Paris Agreement. Chevron has set goals to reduce gas and methane emissions and reduce the GHG emissions intensity of its upstream business.

US independents are not likely to change their business models as long as they are able to continue with shale oil and gas. It is plentiful, and it has a huge dependable internal market – driven by market forces – which is unlikely to change. Those that can survive the current turmoil would also be able to compete in Asian markets.

World change

While the EU is pressing ahead with implementation of its Green Deal and focusing its Recovery Plan on the achievement of climate neutrality by 2050 and a digital future, the world is becoming increasingly divided. This can be summed up in in three main respects:

- An economic/political divide – which inevitably has energy security implications – with a ‘cold war’ in the offing, with the US, and to a certain extent the EU, on one side, and China and to a certain extent Russia, on the other.

- An energy divide, with the EU, and to a lesser extent the US, going green, while Asia, led by China and India, is giving priority to economic growth and energy security and still investing heavily in coal as well as renewables

- An oil and gas company divide, with European IOCs being pushed by NGOs and activist-investors to transition away from oil and gas into renewables, while NOCs in Russia and Asia, and to a lesser extent in the US, carry on focusing their investments in oil and gas.

The challenge in the developing economies of Asia and Africa, especially after the massive impact of Covid-19, is to convince populations that climate change is a priority. What matters is economic recovery.

Only international consensus can move the world towards addressing climate change in a concerted, co-ordinated, manner. The Paris Agreement was a successful outcome of such a consensus. But post-Covid-19 there is increasing divergence, rather than convergence, with the priorities in Asia being economic recovery and energy security, while the EU pushes on with its Green Deal.

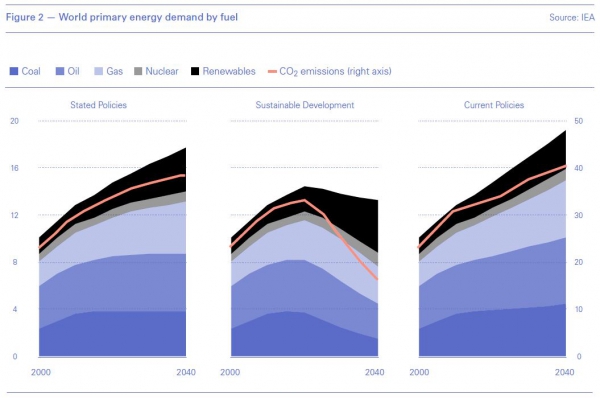

Despite all these developments, and growing pressure from environmentalists, unless the world as a whole undergoes dramatic policy change now – and leaving aside any temporary impact by Covid-19 – most global energy forecasts show fossil fuels to be providing the bulk of the world’s energy well into the future.

IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2019 demonstrates this. Fossil fuels provided 81% of global primary energy in 2018, and under IEA’s Stated Policies scenario they are expected to still provide 74% in 2040 (Figure 2).

The IEA forecasts that while EU’s primary energy demand will decline by 23% by 2040, global demand will actually increase by 24%, driven by Asia. In fact, by 2040 the EU is forecast to consume only about 7% of global energy: China alone will be consuming well over three times as much.

For the world to meet this demand, it will require new investments by oil and gas companies if – despite current oversupply – it is not to turn into supply shortages in the medium to longer term.

With NOCs largely continuing with business as usual, they can and will most likely step in to produce the oil and gas supply the world outside the EU will continue demanding, free from climate change pressure and regulations and investor divestment campaigns.

Challenges

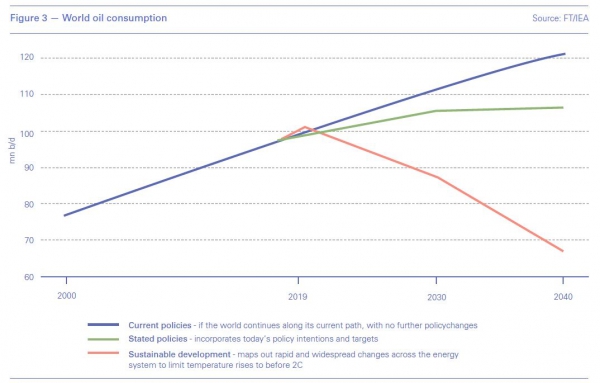

The Covid-19 pandemic upended previous forecasts for oil and gas supply, and especially consumption, in the short term. How the energy world emerges out of the pandemic is not yet clear – even though there is a growing view among oil company executives that “the worst is behind us.” It also depends greatly how the US-China relationship develops.

Oil demand reached 100mn b/d last year and the question is whether it has peaked, as IEA’s Sustainable Development scenario requires if the global temperature rise is to be limited to 2 °C Celsius? (Figure 3).

Another factor impacting transition to lower carbon energy, is low oil and gas prices. Increasing efficiency and technology innovation, including artificial intelligence and better reservoir management, are bringing oil and gas production costs down, supporting competitiveness and profitability into the future.

While oil and gas may be under pressure in Europe, that is unlikely to be the case in Asia – at least not in the foreseeable future. This dichotomy is also reflected on how IOCs and NOCs respond to climate change pressure – or not.

And those that press ahead with net-zero too soon might find themselves exposed.

IOCs that operate in both worlds face a major risk of calling the market wrong: as Shell CEO Ben van Beurden said, oil and gas might peak very quickly and become a “diminishing percentage of the energy mix.” Equally, giving up on them to soon was “just not a smart strategy.” Shareholders will penalise such an outcome but some oil and gas developments – especially major LNG projects – need decades to pay off.

And with the new technologies required to displace today’s oil and gas consumption not yet sufficiently mature or scalable enough – and possibly not for years to come – oil and gas will still be needed well into the future, as IEA shows (Figure 2).

Nevertheless, for oil and gas to continue being a force in the future, the industry will need to lower carbon emissions, including methane at all points of the cycle.

For change to happen in this high-risk environment, IOCs will need strong policy to back them up. This is a major departure from the past, when the cost and technical advantages of certain fuels over others in some applications – gas over oil, oil over coal, coal over wood and so on – were self-evident and needed little push.

But stepping into the unknown and manufacturing blue or green hydrogen for grid or even industrial use and developing the necessary carbon capture and storage sites cannot be undertaken without predictable rules. Some hydrogen will be used in local grids, other hydrogen might well cross national borders and will have to satisfy all the governments involved.

There also need to be minimum differences between prices – particularly between carbon and electricity – in order to finance carbon reduction projects or encourage fuel-switching. These are in the gift of governments and policy-makers who can ration emission allowances, introduce floor prices, set the rules for biogas and biomethane production and consumption, or tax diesel adversely to promote gas, for example.

If the rest of the world, and particularly Asia, does not follow the European model, then any benefits will be limited and the divide between the two worlds will increase.