Emerging Asia: the frontline for LNG [NGW Magazine]

Despite Covid-19, emerging Asia remains a bright spot for LNG demand growth. The International Energy Agency expects emerging Asia, which excludes China and India, to add 35bn m3/yr demand in the period 2019-2025, most of which will be absorbed by power generation and most of which is likely to be met by LNG imports.

The scenario carries with it major uncertainties, but current low prices and the expectation that the LNG market will remain in surplus until at least 2025 removes one key barrier to the development of LNG-to-power supply chains: its price.

LNG is generally more expensive than domestic gas supply but it also faces some degree of policy resistance as it exposes countries to the price risk of international markets. It has to be paid for in hard currency and represents a outflow of funds, which weighs on countries’ balance of payments, even if can be used to add value internally and displace other import dependencies, for example fertilizers.

The exceptionally low price of LNG, the lack of direct cartel pricing and the proliferation of supply points all mitigate these risks.

At $2/mn Btu, LNG is no longer an expensive option, but competitive with domestic gas supply, coming into emerging Asian markets characterised by structural gas deficits, often declining domestic gas production and levels of electricity demand growth that are high relative to GDP. There are few cost barriers to enjoying a fuel that burns more cleanly than fuel oil or coal.

Infrastructure key

One of the impacts of a demand shock is that profitability in the oil and gas supply chain tends to move downstream to areas where profits are dependent on margins rather than production costs versus commodity price.

Refiners do not care about the absolute price of crude oil, but about the margin between crude oil and refined products, while power generators watch the spread between feedstock and generation costs versus electricity prices. In contrast, oil and gas producers do care about the base commodity price, which needs to be above average production costs.

Investment needs to follow this shift in profitability. Even though it may seem like an expensive, long-term play, the oil and gas majors and state oil and gas companies need to refocus investment on the demand side rather than upstream production.

If infrastructure deals for LNG regasification and LNG-to-power projects fall foul of the capital spending cuts brought about by Covid-19, it is likely to do more long-term damage to the LNG industry than Covid-19 itself.

Unlocking the door

LNG demand in any one country can be no higher than the capacity of the import infrastructure and the downstream ability to absorb the imported gas. The continuing development of LNG-to-power supply chains are thus fundamental to emerging Asia’s future LNG demand.

The IEA, in its Gas 2020 report, published in June, sees 60% of the incremental growth in emerging Asian gas demand growth coming from the power sector.

Weak economic growth means domestic emerging Asia utilities, already dependent on lending from multilaterals or export credit agencies, remain financially weak. This is often the result of being caught between low regulated electricity prices and international commodity markets, a pressure eased by low LNG prices. As a result, some oil and gas companies, despite their own capital constraints, are trying to bridge the financial gap.

Thai economy battered

Thailand is expected to suffer more than most other southeast Asian nations from Covid-19 as a result of the loss of tourism. However, it faces a growing structural gas deficit, which is still likely to see LNG imports rise substantially over the next decade.

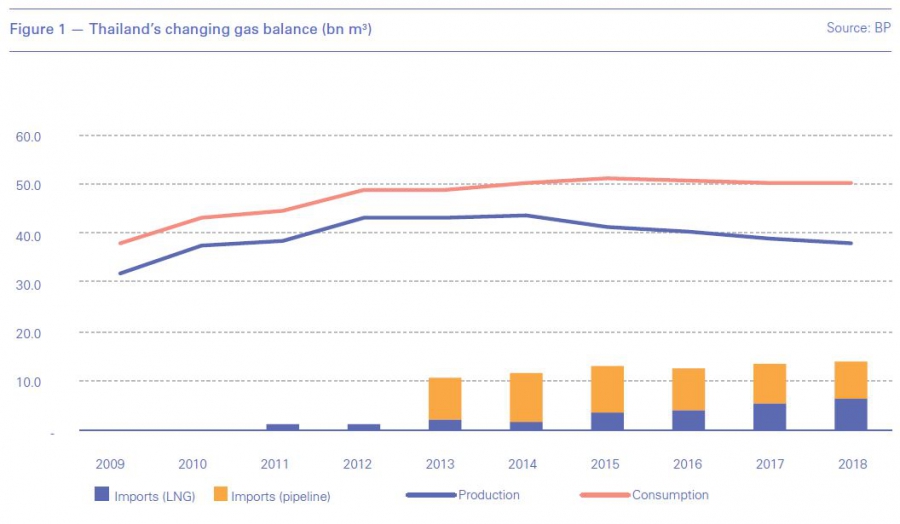

Thailand’s domestic production peaked in 2014 at 43.6bn m3 and had fallen to 37.7bn m3 by 2018, according to BP data. At the same time pipeline imports from Myanmar also dropped from 9.7bn m3 in 2014 to 7.8bn m3 in 2018. LNG imports have filled the gap, rising from 1.9bn m3 in 2014 to 6.8bn m3 last year.

However, Thailand’s ability to absorb more LNG is dependent on deals such as the one sealed in November last year with Japan’s Mitsui and Thailand’s Gulf Energy Development.

The companies plan to spend $1.6bn on a 2.5-GW combined-cycle gas turbine power plant in Rayong province, scheduled for completion in 2023. This is part funded by a $1.36bn financing agreement including the Japan Bank of International Cooperation, Asian Development Bank (ADB), Export-Import Bank of Thailand and private banks. The principal source of feedstock will be from the planned construction by Gulf Energy and state oil and gas group PTT of a 5mn mt/yr LNG import terminal.

Mitsui and Gulf Energy are already building another 2.5-GW gas-fired plant in Chonburi province, which, pre-Covid 19, was expected to be complete in March 2021.

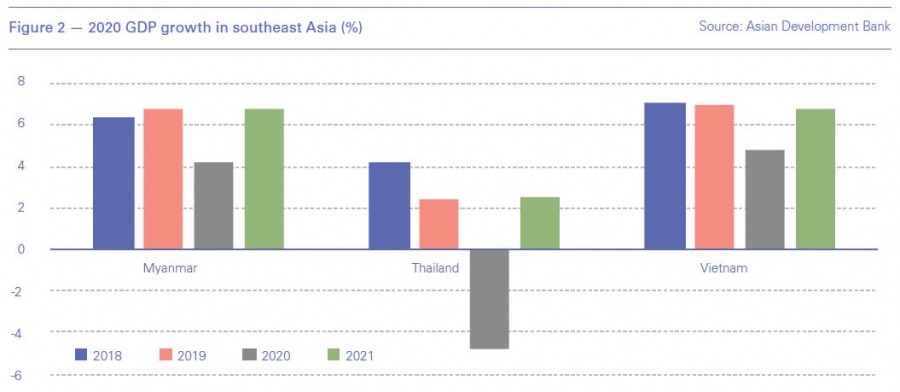

Thailand appears to have dealt well with the Covid-19 crisis in terms of infection control. However, the ADB expects the country’s economy to contract this year by 4.8%. This makes it less likely that the country would import 36mn mt/yr of LNG by 2030, as government officials had said before Covid-19.

Vietnamese resilience

Vietnam’s LNG ambitions also only look likely to be realised through a combination of state support and foreign capital. In June, the Vietnamese government announced that US oil major ExxonMobil was looking at investing in a 4-GW gas-to-power project in the industrial city of Hai Phong and a 3-GW gas-to-power project in Long An province.

While ExxonMobil is a partner in the development of Vietnam’s Ca Voi Xanh gas field, LNG is expected to be the main feedstock for the gas plants, if they are built.

Russia’s Gazprom is getting into LNG-to-power supply chains as well. The company’s international arm was selected by the Vietnamese government in April as an investor in a 340-MW coastal gas plant in Quang Tri province.

Independent Russian gas company and LNG producer Novatek also signed a memorandum of understanding on the development of a Vietnamese gas plant fed by LNG in June last year.

Vietnam, like Thailand, appears to have managed the Covid-19 outbreak effectively. Moreover, it is expected to sustain economic growth of 4.8% this year, according to the ADB, rising to 6.8% in 2021. This will make it the fastest growing economy in southeast Asia.

Prior to the virus outbreak, state company PetroVietnam was forecasting a gas deficit of more than 2bn m3 in 2023, rising to 7bn m3 by 2030.

Myanmar enters the LNG market

A bright spot in the LNG market in southeast Asia has been the start of LNG imports to Myanmar with Malaysia’s Petronas reporting the delivery of its first LNG cargo onboard the 27,500 m3 CNTIC VPower Global in early June. Another, larger cargo onboard the 162,000 m3 Golar Kelvin was also reported to have loaded at Bintulu, Sarawak, destined for Myanmar, although it is not clear that Myanmar has the capacity to berth the vessel directly.

The ADB forecasts the country’s economy will grow by 4.2% in 2020, the second fastest rate in southeast Asia. Myanmar’s rising demand for gas is eating into its capacity to export gas by pipeline to Thailand, while domestic production dropped from 19.2bn m3 in 2015 to 17.8bn m3 in 2018.

Upstream, agreements were reached between France’s Total (40%), Australia’s Woodside (40%) and Myanmar’s MPRL E&P (20%) to develop the ultra-deepwater Block A6 in the Gulf of Bengal in December last year, following successful appraisal drilling in 2019.

A production start date of 2023 has been mooted, but this looks ambitious in the current environment and both Total and Woodside have announced large cuts in capital spending this year as a result of Covid-19. If developed, Block A6 would feed into the Yadana platform complex which supplies gas to Myanmar and Thailand.

With its gas balance deteriorating, Myanmar is rushing forward its LNG import capacity to source additional feedstock for power generation in an election year. Annual electricity demand growth is reported to be running as high as 17%.

China link

The ability to import LNG into Myanmar may have wider significance. Most of the investment capital for LNG regasification and gas-fired power plant development in the country is coming from China. Myanmar’s exports of gas by pipeline to China rose to about 4bn m3 in 2019, according to Chinese import data, but remain significantly below the Myanmar-China pipeline’s capacity of 12bn m3.

The Myanmar-China oil and gas pipelines were completed in 2013, bringing oil and gas supplies into southwest China at Ruili in Yunnan province far from China’s main east coast LNG terminals and oil import facilities. In addition to reaching into China’s southern hinterland, the pipes have significant strategic importance for Beijing because they do away with shipping LNG through the narrow Strait of Malacca, which is the Achilles’ heel in China’s energy security strategy in the event of conflict.

Initial LNG supplies will be used to supply emergency power generation in and around Yangon, but as well as meeting domestic needs, the development of LNG import capacity could lead to the onward transit of regasified LNG cargoes via pipeline into southwest China.